As the Lok Sabha seats in India’s largest farming belt — Haryana and Uttar Pradesh — go to the polls, Congress MP Rahul Gandhi has once again promised to waive off farmer debts if the Congress-led coalition is voted to power. The last pan-India farm loan waiver was done by the UPA government in 2008 in the form of a ₹60,000 crore economic package. Incidentally, the waiver came a year ahead of the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, in which the UPA was re-elected with a bigger majority.

Addressing an election rally in Haryana’s Charkhi Dadri on May 22, Mr. Gandhi promised to waive farmers’ debts and guarantee them Minimum Support Price (MSP) for their crops. Claiming that Prime Minister Narendra Modi felt farm loan waivers would “spoil the farmers,” he vowed, “We are going to ‘spoil the farmers’ when we return to power and waive their debts, not just once but again and again….We will form a commission and every time farmers need a debt waiver, the panel would let us know and we will do that.”

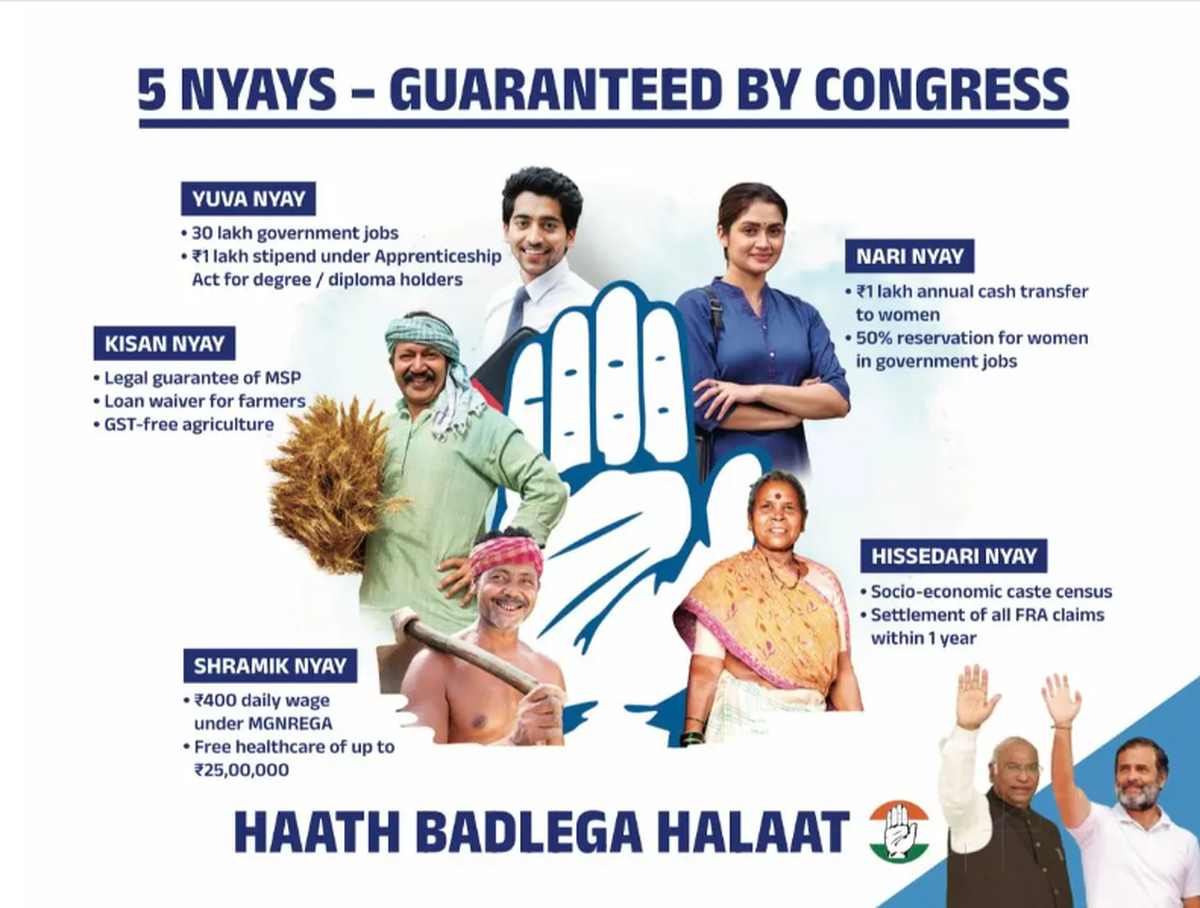

Congress’ Paanch Nyay gurantees

The Congress has released five sets of ‘guarantees’ in which it promises farmers a Standing Loan Waiver Commission to systematically evaluate and recommend debt waivers, apart from the immediate loan waiver which Mr. Gandhi has promised. Farmers, who have been protesting in various States (especially at Delhi’s borders) since February, have been asking for an immediate farm loan waiver and legal guarantee for MSP for all crops procured by the Centre. As of 2022, outstanding agricultural debt stood at ₹18.5 lakh crores.

How do farm loan waivers work?

Scheduled banks offer loans to individual farmers or group of farmers for agricultural or allied activities such as dairy, fishery, animal husbandry, poultry, bee-keeping and sericulture. Short-term (up to 18 months) loans are offered for raising crops during two seasons – Kharif and Rabi, while medium (more than 18 months up to 5 years) and long-term (beyond 5 years) loans are offered for purchasing agricultural machinery, irrigation and other developmental activities. Loans are also available for pre-harvest and post-harvest activities such as weeding, harvesting, sorting, and transporting farm produce. Most loans have a repayment period in installments up to five years, and interest rates vary depending on the nature of loans and the issuing banks.

A good harvest bodes well for both the farmers and the banks as installments get paid on time. However, in case of a poor monsoon or natural calamities, farmers may be unable to repay loans on time. As seasons go by, the loans get compounded, adding to the distress of farmers, coupled with strain from crop loss and other damages. In such situations, the Centre or State government steps in, offering a waiver of penal interest or loan interest, rescheduling loans or a full waiver of outstanding farm loans. The liability of repayment to the banks is transferred to the government.

Loan waivers are usually selective, explains Businessline. It depends on loan types (small, medium or long-term), the categories of farmers or loan sources. The waivers are introduced via a new scheme by the government, making a budgetary allowance for absorbing the debts.

Why do farmers need a waiver now?

“Farmers are indebted hence they are asking for waivers. We have seen protests due to it and it is during elections when everyone makes their claims,” says Dr. Dipa Sinha, Assistant Professor, School of Liberal Studies at Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University Delhi. Speaking to The Hindu about farmer distress at large, she adds, “Farm distress is due to many reasons and farmers have made other demands too, like the legal guarantee for MSP.”

Image for representation

| Photo Credit:

AKHILESH KUMAR

Farmers are plagued by larger issues like disputed land holdings, low ground-water reserves, bad soil quality, rising costs of farming inputs (seeds, fertilizers, water, fuel, electricity) and low crop productivity. Due to a lack of assured remuneration for harvest, farmers are forced to borrow funds to tide through expenses, Businessline explains. The lenders are not always banks, as several small farmers do not have access to credit, leading to a dependence on private lenders (land owners or rich farmers), who levy exorbitant interest rates on such loans. This is why these indebted farmers depend on such loan waivers.

“Waiver is not the long-term solution to indebtedness. It is about the larger reforms in agriculture so that farmers don’t end up in a situation where they need a waiver. If you don’t do that (reform) and farmers end up in such a situation, then you are forced to bail them out,” explains Dr. Sinha. Terming such waivers as inevitable, Dr. Sinha draws a parallel, “If you have a fever, you have to give paracetamol (medicine). You cannot avoid it. However, you should take necessary steps, so that you don’t get the fever again.”

When were farm loans last waived?

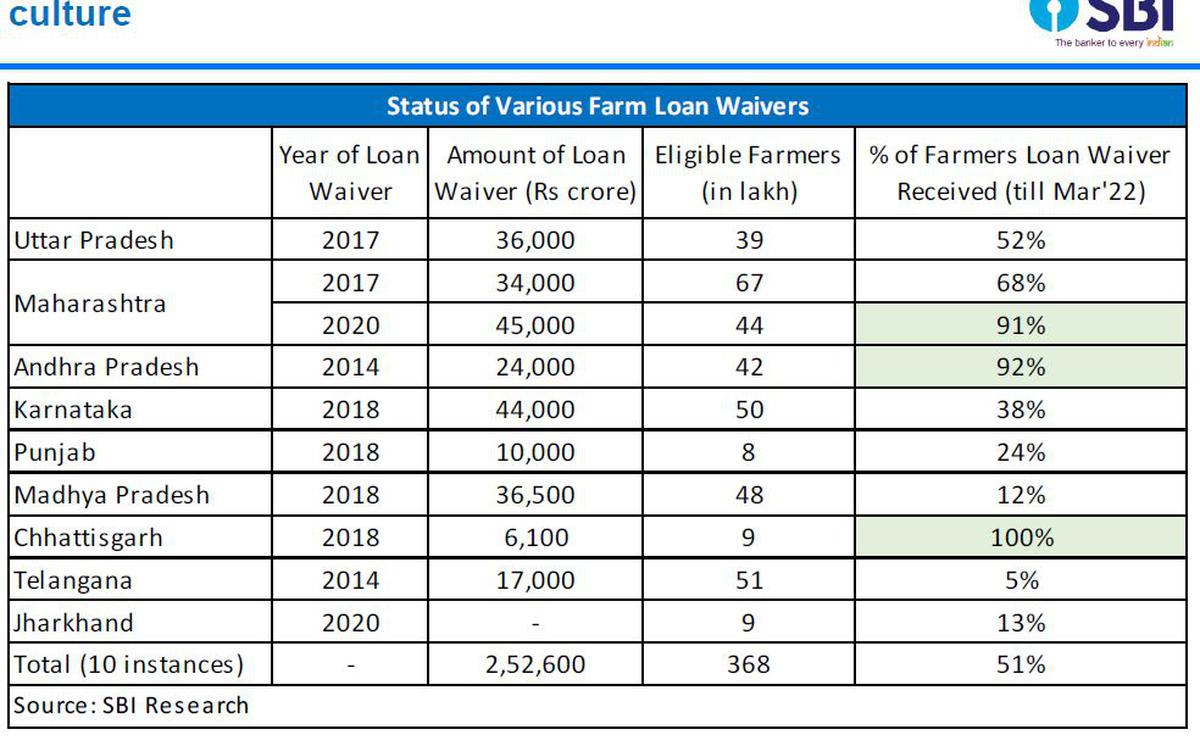

Despite repeated demands from farmers for a pan-India loan waiver, the Modi government has refused to budge, often passing the buck to State governments. According to a study by State Bank of India (SBI), Andhra Pradesh and Telangana implemented a loan waiver in 2014, followed by Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra in 2017, Karnataka, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh in 2018 and lastly, Jharkhand and Maharashtra again in 2020. The total amount of debt waived off over these ten instances is ₹2.52 lakh crores.

Apart from these, one of the largest loan waivers in Tamil Nadu was announced by the AIADMK government in February 2021. Announcing a ₹12,110 crore-scheme ahead of the State elections in April that year, CM E. Palaniswami said outstanding short-term crop loans of all farmers will be waived off. In 2016, the AIADMK government had written off loans for around 12.02 lakh small and marginal farmers, owning land up to 5 acres, to the tune of about ₹5,320 crores.

The first pan-India loan waiver was done in the 1990-91 Budget when the V.P. Singh-led National Front Government was in power. Introducing the Agricultural and Rural Debt Relief Scheme (ARDRS), then-Finance Minister Madhu Dandavate stated that the National Front government would provide relief to farmers for up to ₹10,000 on select loans. As on October 2, 1989, the loans availed by farmers from cooperative banks and regional rural banks were eligible for relief under the ARDRS scheme, which was allotted ₹1000 crores. The scheme came to a close on March 31, 1991 and was not renewed.

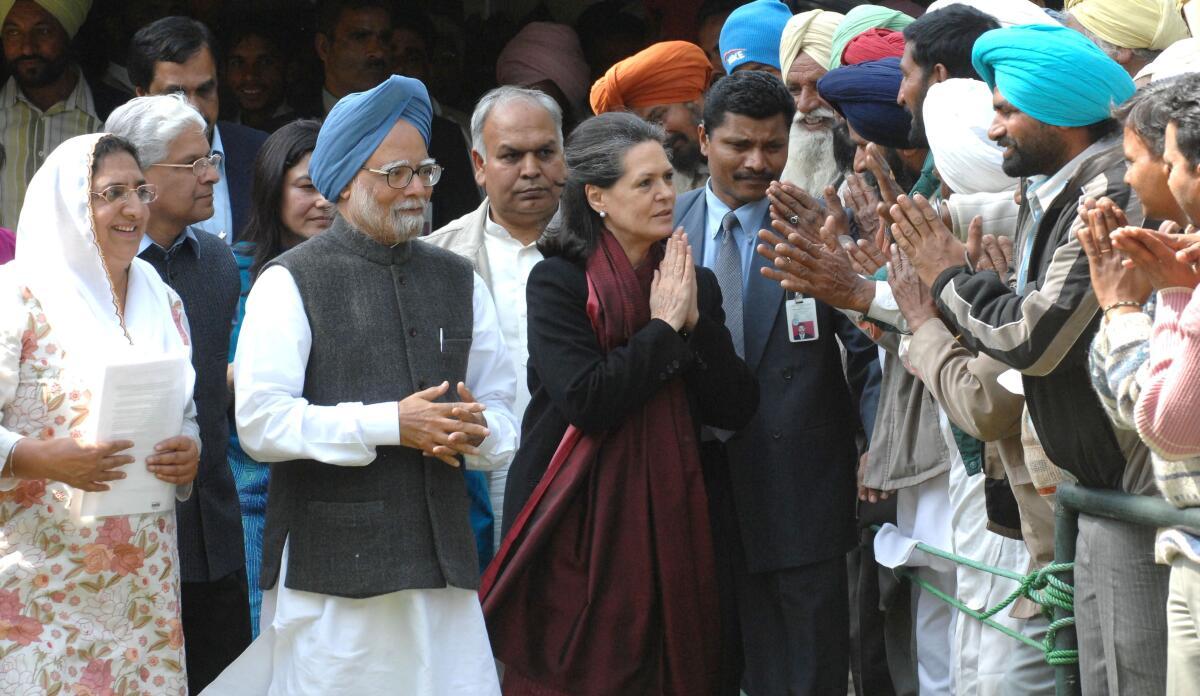

File photo: Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh along with UPA Chairperson and Congress President, Sonia Gandhi being greeted by the farmers from Punjab who met them to thank the UPA Government for waiving off their loans, watched by Punjab Congress Chief, Rajinder Kaur Bhattal (ext L) in New Delhi on February 25, 2008

| Photo Credit:

S. Subramanium

The second such instance of a pan-India loan waiver was announced by then-Finance Minister P Chidambaram during his 2008-09 Budget Speech. Under the Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme (ADWDRS), 2008, short-term and investment loans disbursed to marginal, small and other farmers by scheduled commercial banks, regional rural banks, cooperative credit institutions and local area banks up to March 31, 2007 and overdue as on December 31, 2007, and remaining unpaid until February 29, 2008 were eligible for relief or waiver.

With an allocation of ₹60,000 crores, the entire ‘eligible amount’ was waived off for marginal and small farmers (< 2 hectares of land). In case of ‘other farmers’ (> 2 hectares of land), a one-time settlement (OTS) of 25% of the eligible amount was offered as a rebate, if the farmer pays the remaining 75% of the balance. The rebate would be 25% of the loan amount or ₹25,000, whichever was higher, subject to the balance payment condition. The OTS relief was estimated to cost ₹10,000 crore for the Centre, while the debt waiver was pegged at ₹52,000 crores.

What are effects of such waivers?

According to a NABARD report, the 1990 ARDR scheme cost the Central government ₹7825 crores. States were forced to take additional loans from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to cover their share of the loan waivers and 3.2 crore farmers (53% of the borrowers) were beneficiaries of the scheme. This totalled to one-third of the outstanding farm loans, which were wiped off.

Similarly, the 2008 ADWDR scheme cost the government ₹52,000 crores and over 2.9 crore farmers benefitted from the scheme. However, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report concluded that the scheme had favoured several ineligible farmers and a large number of deserving small and marginal farmers were left out during its implementation. The CAG report found that no records were maintained of farmers’ applications accepted or rejected by lending institutions, or how many fresh loans were issued due to debt waiver/relief.

A NABARD study on the impact of farm loan waivers from 1987 to 2020, found that farm loan waivers were announced without any development agendas or ideologies (be it a right-wing or left-wing government), and there was no link between waivers and drought intensities. Till 2016, waivers were found to be announced by State governments who could fiscally afford it. After 2016, high fiscal debt did not deter such announcements, while the timings of such announcements were found to be crucial. Any such announcements closer to elections reaped greater gains for the party in power. Of the 21 State governments which announced waivers soon before State polls, only four lost.

Farm loan waivers between 2014 and 2022

A more recent SBI study (2022) found that only half of the beneficiaries of the nine farm loan waivers announced by State governments since 2014 have actually received write-offs. Maharashtra, which announced two waivers in 2017 and 2020, ensured that 68% and 91% of the beneficiaries received write-offs. The poorest implementation was by Telangana in 2014, where only 5% of 51 lakh farmers eligible for write-offs received it. States like Madhya Pradesh (12%), Jharkhand (13%), and Punjab (24%) see lower rates of implementation, while States like Chhattisgarh (100%) and Andhra Pradesh (92%) have effectively implemented such waivers.

The study concludes, “Despite much hype and political patronage, farm loan waivers by States have failed to bring respite to intended subjects, sabotaging credit discipline in select geographies and making banks and financial institutions wary of further lending,” terming such waivers a ‘self-goal.’

What are other alternatives?

“Agriculture is a sector where markets won’t work, and it is hugely subsidised and supported by governments across the world. It is not just about direct subsidies to the farmers but also about creating the larger infrastructure to make agriculture more viable. This needs a number of steps to be taken, like irrigation, electricity, access to seeds, fertilisers, research in agriculture, and extension services,” says Dr. Sinha.

Recommending more public investment in agriculture, she adds, “If you look at the investment in agriculture as a proportion of total expenditure or GDP, it has been falling per year. Whichever party comes to power needs to have a long-term policy for agriculture.” When asked if the now-repealed farm laws were a solution to India’s agrarian crisis, she replied in the negative. “Those farm laws were reducing the support of the government even more.”

Amritsar: Workers scatter wheat for drying after heavy rains in the city, at a grain market in Amritsar, Friday, April 23, 2021.

| Photo Credit:

–

One of the biggest farming States in the nation is Punjab, which is facing severe depletion of ground water reserves and degradation of soil due to overuse of urea. The State’s farmers have largely stuck to growing wheat and rice, even as farmers in neighbouring Haryana have switched to oilseeds.

Speaking about this vicious cycle plaguing Punjab, Dr. Sinha says, “Farmers are businessmen like any other. It is not (due to an) affinity to wheat and rice that they are growing it. In Punjab these are the only two crops which are viable because the government procures it. If they incentivize mustard or pulses, farmers will make the shift. They made the (initial) shift to wheat and rice through policy – via the Green Revolution.”

While it has promised several schemes to boost farm income, the Modi government has not promised any farm loan waivers if elected for a third time. Meanwhile, farmers continue to protest being caught in debt traps.