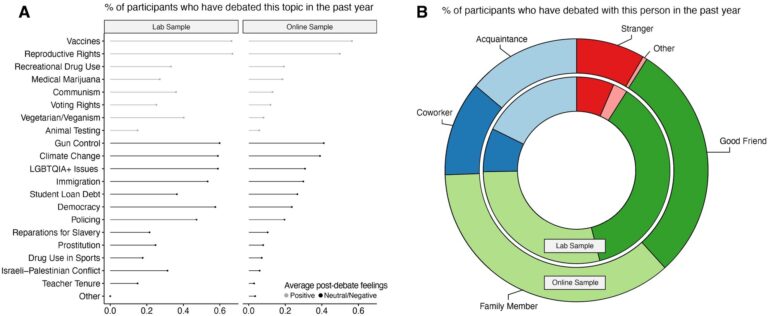

Topics and debate partners in lab and online samples. The figure shows the results of Surveys 2a-2b, in which participants were asked about their experiences debating a range of issues in the past year. Credit: Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-55131-4

× close

Topics and debate partners in lab and online samples. The figure shows the results of Surveys 2a-2b, in which participants were asked about their experience debating a set of issues in the past year. Credit: Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-55131-4

One quick scroll through social media or news sites can make it seem like America is a country on edge, where casual comments often spark heated arguments, and according to Gallup, partisanship is on the rise while trust in institutions is on the decline.

But this perception may not accurately reflect the nature and frequency of political debate among ordinary Americans, according to a new study co-authored by Erica R. Bailey, an assistant professor at Berkeley Haas. In three studies with nearly 3,000 participants, the researchers found that most of the debates took place among family and friends, not with strangers on social media. What’s more, participants often felt more positive after such discussions.

“We have this misconception because negative media and negative interactions on social media are amplified by algorithms, coupled with the fact that we’re very good at remembering negative information,” Bailey says. “It creates this perception that we’re all just fighting strangers.”

In fact, one study of a representative sample of nearly 2,000 Americans showed that people overestimate how often other people engage in arguments, a misconception that is especially pronounced when it comes to online arguments with strangers. According to researchers, this misperception comes with a psychological cost and is contributing to a growing sense of despair about America’s future.

“Our findings suggest that Americans experience a false reality about argument situations, which may unnecessarily undermine their hopes for the future,” the researchers said in the study published in the journal Neuropsychiatry. Scientific Reports Co-authors are Michael W. White, Sheena S. Iyengar and Modupe Akinola of Columbia Business School.

Difficult and sensitive conversations

Bailey says the project began with her reflecting on her own experiences. “When I think about who I talk to about important issues, it’s my colleagues and friends,” she says. “Online interactions feel like a waste of time. Why should I have difficult, sensitive conversations with people I don’t know or trust?”

Bailey, the authenticity researcher, says online discussions often feel contrived, and people are often reluctant to openly share their experiences, just trying to make a point. But while we have a ringside seat to the most heated online debates every day, we don’t have a peek into people’s private dinner table conversations, making those conversations harder for researchers to observe, replicate and measure.

Perceptions of a “typical” debate

In the first study, the researchers asked 282 participants to freely recall arguments they had recently witnessed or participated in. About half of the participants described arguments they had seen online and said that these interactions were more negative than positive.

Interestingly, respondents believed these instances were representative of typical arguments, highlighting the perception that arguments, especially online arguments, are generally viewed as negative.

Personal experiences with debate

The second phase involved two studies to explore individuals’ discussion experiences in more detail: the first involved 215 people from a behavioral science lab, and the second involved 526 people recruited online.

Participants in both groups were asked about topics they had discussed in the past year, who they had discussed them with, and how they felt after the discussion. They were also asked to choose a topic they had discussed from a list of 20 common topics, including climate change, gun control, gender identity issues, and reparations for slavery.

Results revealed that reproductive rights and vaccines were the most commonly discussed topics, while other contentious issues such as policing and immigration were discussed less frequently. Most topics were discussed by less than half of the participants. Contrary to the common belief that online interactions are hostile, participants said the majority of their discussions took place with family, friends, and other close people.

In terms of emotional impact, online participants reported that their average feelings after the discussion were positive, suggesting that discussions often end on a constructive note, even on divisive topics. Lab participants’ feelings were neutral, neither overwhelmingly positive nor negative.

“This was a surprise to me because I didn’t expect people to report feeling positive after the debate,” Bailey says. “This suggests that, at least on some topics, people are good at finding middle ground or at least leaving on a positive note.”

Measuring misconceptions and their impact

The third study looked at how Americans perceive debates compared to their actual experiences: Nearly 2,000 Americans in a nationally representative sample were randomly assigned to either self-report their own debate experiences or predict how often others engage in debates.

The results were shocking: in nearly every category, people significantly overestimated the frequency of arguments, especially online arguments with strangers (the exception being in-person arguments with family members). What’s more, this overestimate was strongly associated with feelings of hopelessness about America’s future.

Implications

The study highlights a significant gap between perception and reality. “Taken together, these findings suggest that a ‘typical’ argument is fundamentally different from strangers typing to each other behind a computer screen,” the researchers wrote. This misconception may be due to the visibility and spread of negative content on social media platforms, where extreme views are often amplified over moderate or conciliatory views.

Second, the findings suggest that these misconceptions may contribute to a society-wide sense of despair about the state of American politics and the future of democracy. Assuming that debates are overwhelmingly negative and frequent may lead people to perceive political engagement and debate as fruitless. (The researchers cautioned that this relationship is primarily correlational.)

Finally, this study points to the need for interventions that not only make the debate more productive but also adjust the public’s perceptions of the political debate. Educating the public about the actual dynamics of the debate could help to alleviate feelings of despair and promote a more constructive and hopeful engagement in the political process.

For more information:

Erica R. Bailey et al., “Americans Misunderstand the Frequency and Form of Political Debate.” Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-55131-4

Journal Information:

Scientific Reports