There is no rule of law under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Executives of foreign companies and investment companies investing in China should know this fact. Yet many companies are tempted by the profits and take risks, confident that they will stay in the good graces of the dictatorial regime. But how safe is investing in China? When will the leaders of foreign companies realize that they have fallen into a trap?

The trap is a shifting landscape of Chinese policies and laws that the Chinese Communist Party manipulates to ensnare unsuspecting companies. While domestic companies frequently fall victim to the trap, foreign companies accustomed to operating under the protection of commonly understood legal rules are especially vulnerable.

Unlike the United States and other societies governed by the rule of law and an independent judiciary, the Chinese Communist Party has long relied on a combination of policy and law to maintain control of the country and secure its position of privileged power. Whenever the Party needs to, it can arbitrarily decide when policy follows law and when law follows policy. When the Party wants to dictate policy, the law is merely paper. But when the Party wants to punish dissent or suppress foreign businesses, it can invoke any number of crimes on the legal code to stifle dissent, lending a semblance of legitimacy to what is in reality reckless repression or outright theft.

This dynamic has been at work since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Eager to attract foreign investment, the Chinese Communist Party leadership pretended to enact the reforms the West expected. They enacted written laws they never followed, held elections that amounted to the endorsement of one-party candidates, and publicly launched an “anti-corruption” campaign that was a targeted purge of individuals who threatened their authoritarian rule. This played well in conversations with foreign leaders and officials, but most people knew it was a facade.

At the same time, the CCP has authorized authorities at all levels, from central, provincial, and local leaders, to offer privileges and policies to attract foreign investment, including reduced or no taxes (e.g., no taxes for three years followed by a significant tax cut for five years), preferential real estate prices, below-market land lease fees, faster approval of mortgage loans, and simplified administrative procedures, to name just a few of the benefits designed to encourage engagement in China.

But geopolitical vagaries, domestic economic concerns, and suspicions about companies that have grown too big or too influential are triggering change, and what once seemed solid contracts and agreements are now sinkholes. This is the trap: privileges granted by local policies are suddenly declared to violate Chinese law.

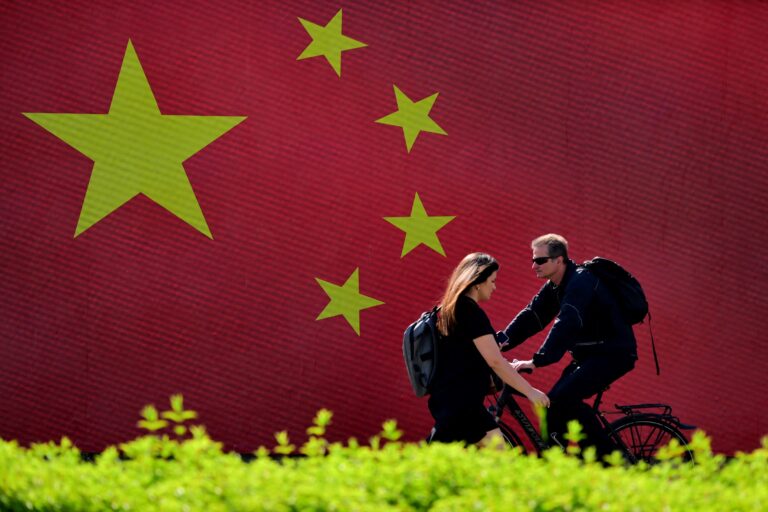

Andrei Isakovic/AFP/Getty Images

When the CCP changes its mind, the locally implemented “preferential policies” suddenly become not only outdated, but illegal. What seemed like a great deal was actually part of a policy trap. But at that point, it’s too late to regret: the law only serves the CCP’s interests, and existing contracts that end up in court are as good as a blank slate.

Perhaps that is the case with Foxconn, the global semiconductor manufacturer. After years of operating in China, Foxconn was investigated by the Chinese Communist Party last fall for alleged tax violations. The result? A small fine of $2,800 for a key supplier to Apple and other multinationals. But the so-called investigation was conducted in secrecy, and documents related to the case remain buried deep within the Chinese Communist Party-controlled judiciary.

Who can say what the real value of the backroom “settlement” was, not just to Foxconn but to the countless companies that have found themselves in similar situations over the years?

I often say it’s like having your teeth pulled and then being forced to swallow them to hide your humiliation and victimization. No one notices the coercion by a corrupt regime, which will create even more defenseless victims in the future. And it’s a win-win: the Chinese Communist Party, which wants to hide its wrongdoings and make future profits, and the corporate leaders, who don’t want to have their reputations tarnished by publicly dropping their stock prices, even if they are suspected of tax evasion.

While foreign companies are pouring money into China, locals are eager to move as much wealth as they can out of the country and safely store it in jurisdictions with a strong rule of law, such as the United States and Canada. Local investors fear specific actions aimed at them, but at the same time they recognize the inherent instability of China’s Potemkin village economy. Can foreign companies eliminate the risk of losing their entire investment in China, given the actions of China’s close ally, Russia? Partnering with a communist dictatorship is inherently risky.

I have shown you the trap. How many more will fall into it?

Chen Guangcheng is a distinguished research fellow at the Catholic University of Japan’s Center for Human Rights.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Rare knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom, seeking common ground and finding connections.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom, seeking common ground and finding connections.