It’s like watching a bad sequel to Star Wars. Pakistan’s Prime Minister’s Office’s announcement about Foreign Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s planned visit to China for the “launch” of the second phase of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) was lukewarm, listing June 4 as a date that is “subject to slight change.” In other words, Beijing has yet to confirm the date. Moreover, the announcement of CPEC-II has been running since 2021. China has done plenty of things elsewhere that should concern India regarding the “corridor” (think of the road across Shaksgam in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK)), and CPEC itself, despite the new phase, seems to be stagnating.

The talk of a new phase was puzzling to say the least. In 2023, Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng announced five new corridors proposed in a letter from President Xi Jinping. Chinese sources said they called for jointly building a growth corridor, a living improvement corridor, an innovation corridor, a green corridor and an open corridor. Nobody knew what that meant, especially since there was no sign of innovation whatsoever. What’s even more interesting is how Xinhua described the corridor. “Launched in 2013, CPEC is a corridor connecting the port of Gwadar in southwest Pakistan with Kashgar in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwest China, with a focus on energy, transport and industrial cooperation,” Xinhua said. That means it’s the projects that connect the two hubs that are of the utmost interest to Beijing. During his visit last year, Vice Premier He Lifeng only saw it as an “important pioneering project” of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Khurram Hussain’s excellent article makes the same point, adding that the original text refers to the Xinjiang-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which would benefit Xinjiang and provide access to Gwadar for exports.

Now, let us consider some concrete actions ahead of the visit. After a frantic search for “deliverables”, the government has announced “approval” for a $2 billion road project. This is for the 241 km Thakot-Raikot section of the Karakoram Highway (KKH), following previous works such as the Havelian-Thakot road. Seismic maps show that this route is subject to severe landslides. However, a look at the details of this approval shows that its actual implementation is questionable, given that not only will the amount be reduced, but it will be undertaken only with due economic and financial diligence. China has submitted a joint feasibility study, but its contents are unclear. Pakistan cannot pay for the project, and the National Highways Authority has already exceeded the requirement by about 1.7 trillion Pakistani rupees, which cannot be met from the public sector development fund. Moreover, the problems plaguing the KKH have been evident since at least 2017. This is a highly environmentally sensitive area, and large projects will cost a lot of money.

The Main Line 1 railway project, which Pakistan is desperate for Beijing to fund, has likewise been under discussion for years. As Hussain points out, China hasn’t even done a feasibility study. When then-PM Kakar attended the BRI meeting in October, the only thing mentioned in the joint statement was a “common understanding” on the project. This is not much. It was originally meant to be a PSDP project, but was eventually adopted into CPEC’s planning, with the most expensive cost at about $6.8 billion to upgrade the Karachi-Peshawar link. There is no reason to think Beijing will act aggressively when its own economy is in distress and Pakistan’s economy is in near-catastrophe.

This is not to downplay the amount spent so far. Given the uncertainty, the real figure is estimated to be around $62 billion, up sharply from the previous estimate of $46 billion. That’s a lot of money. Not surprisingly, elected representatives say China is irritated by Pakistan’s “can-do” attitude, while Pakistanis themselves are concerned that Chinese projects are about three times more expensive than international standards. Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund recently warned against using its money to repay the 493 billion Pakistani rupees owed to Chinese power plants, 77% higher than last year. That means Chinese companies are unlikely to get their money back anytime soon. That makes it unlikely other companies will be keen to invest in Pakistan. As Pakistanis say, in terms of cost per unit, it’s very profitable for Chinese companies.

The Gwadar conundrum continues. While the port itself continues to decay, a huge international airport is being built fairly quickly and is due to become operational next year. The airport and port were supposed to be part of a special economic zone that aims to become like Shenzhen, whose population has grown from 60,000 to 17 million in just 40 years since the port was built. But China insists that the road and rail network to the port should be Pakistan’s responsibility. Pakistan’s progress has been slow, and to make matters worse, Baluch rebels have launched a series of attacks against the Chinese, fueled by local disillusionment with “promises” of local development. To assuage local sentiment, a friendship hospital has been established (one of the few grants provided by China), as well as a desalination plant. But the airport is interesting. It could be the place where China could provide all kinds of support to the Pakistani Air Force and Navy in the event of a war with India. Gwadar is up and running, and run entirely by the Chinese. It’s just not yet commercialized.

And finally, among all the vaguely named corridors, one stands out: agriculture. This one is likely to be inspired. After the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, China is growing anxious about its reliance on food imports. In February 2023, government documents focused on the need for food security, and President Xi Jinping was implementing policies to increase agricultural land area. According to a report released in January by the Council on Foreign Relations, between 2000 and 2020, the country’s food self-sufficiency rate fell from 93.6% to 65.8%. Pakistan’s fertile POK valley is on Beijing’s doorstep and easily accessible. China faced a surge in attacks across the country in March, including in Besham, but according to social media handles, this was carried out by Pakistanis themselves, to worsen the rapidly warming relationship between China and Afghanistan. In fact, that is exactly what Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mojahid told the media.

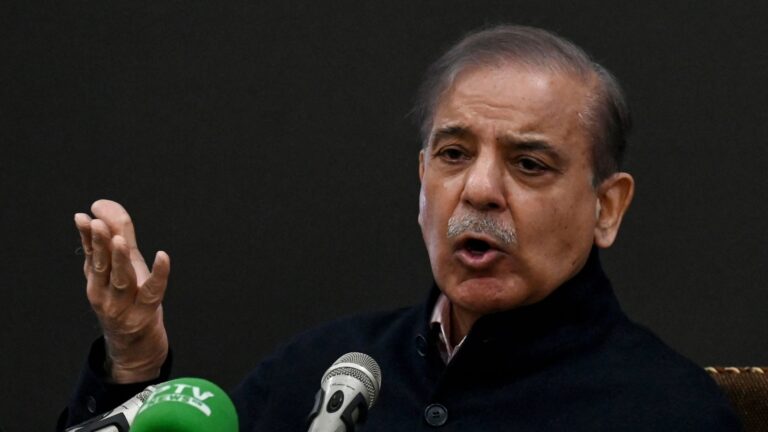

In Beijing, Mr. Sharif will be questioned about all this. The joint statement will be full of “iron brothers” and vows of eternal friendship, but little else. But the fine print must be noted. China’s penetration into Pakistan is not over. In fact, it is likely to increase further in an effort to bring back investments. After all, there is a solid defense relationship between the two countries, and there are other projects, such as Chinese-made submarines being built in Karachi. This is by no means over. The money may be less, but the exploitation is not. Remember the Chinese professor who told Pakistanis bluntly that CPEC is not a charity? Well, it’s time to learn that lesson.

This article was written by Tara Kaluta, Director, Land and Air Studies Centre (R&A), New Delhi.