Editor’s note: Mike Chinoy He is an adjunct senior fellow at the US-China Institute at the University of Southern California and a former Beijing bureau chief and senior Asia correspondent for CNN. He recently published “Assignment China: An Oral History of American Journalists in the People’s Republic of China.” This interview is excerpted from the book.

CNN

—

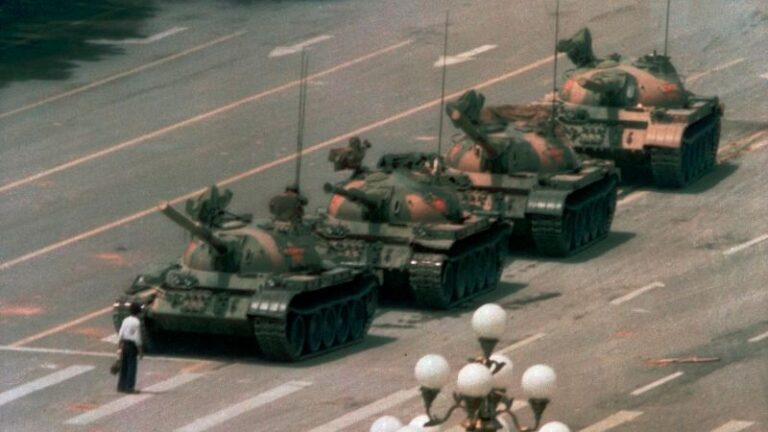

The photo is iconic: An unidentified man in a white shirt and carrying a bag in each hand stands against a column of tanks on Beijing’s Yonghe Avenue after the Chinese Communist Party ordered the military’s bloody crackdown on pro-democracy protesters.

Photos and footage of the so-called “Tank Man” have become iconic images of the Tiananmen Square massacre, which marked its 35th anniversary on Tuesday.

On the night of June 3, 1989, after nearly two months of student and worker demonstrations calling for faster political reform and an end to corruption, a convoy of armed troops entered central Beijing to clear the square. It was a bloody massacre, with witnesses saying tanks ran over unarmed protesters and soldiers fired indiscriminately into the crowd.

To this day, the massacre remains one of mainland China’s most sensitive political taboos and mentioning it is heavily censored; commemorating the massacre can lead to imprisonment. Chinese authorities have not released an official death toll, but estimates range from several hundred to several thousand.

Isaac Lawrence/AFP/Getty Images

People hold candles during a rally marking the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre in Hong Kong on June 4, 2017. The former British colony was the only place in mainland China where such gatherings were allowed, but a recent crackdown by Beijing has brought an end to the decades-old tradition.

Still, every June 4th since then, diaspora communities around the world and survivors of the protests in exile have commemorated the event, frequently re-sharing historic photos taken by then-Associated Press photographer Jeff Widener and footage shot by CNN crews.

The photographic journey also captures the tension and fear of the time – smuggling equipment and film past authorities and borders – at a time when the Chinese government was desperately trying to control the message being sent to the world and was trying to block all American news outlets, including CNN, from broadcasting live from Beijing.

These interviews, excerpted from “Assignment China: An Oral History of an American Journalist in the People’s Republic of China” by Mike Chinoy, CNN’s Beijing bureau chief at the time of the crackdown, provide a behind-the-scenes account of perhaps the most famous moment of the crisis. Chinoy was on the scene, broadcasting live from a balcony overlooking the scene, and speaking to eyewitnesses during and after the historic event.

Infiltration and equipment smuggling

On Monday, June 5, 1989, Beijing was reeling from the previous day’s crackdown. Liu Xingxing, a photo editor for the Associated Press in Beijing, asked Weidner to help him photograph Chinese troops from the Beijing Hotel, the best vantage point in the square now under military control.

Widener, who flew in from the news agency’s Bangkok bureau a week ago to help with the investigation, previously told CNN that he was injured when he was hit in the head by a stone and contracted the flu as the crackdown began.

He hid his camera equipment in his jacket, with a 400mm long lens in one pocket, a doubler in the other, film in his underwear, and the camera body in his back pocket, and set off.

Jeff Widener/AP

A young woman is caught between a civilian and a Chinese soldier near the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on June 3, 1989.

“I was cycling towards the Beijing Hotel and saw rubble and a charred bus on the ground,” he said. “Suddenly, four tanks with soldiers with heavy machine guns approached. As I was cycling, I thought to myself, I can’t believe I’m doing this.”

“I heard rumours that other journalists had their film and cameras confiscated. I had to figure out how to get into the hotel,” he added. “I looked into the dark lobby and saw a Western university student. I went up to him and whispered, ‘I’m from the Associated Press. Can I get to my room?’ He immediately understood and said, ‘Of course.'”

The young man was an American exchange student named Kirk Martensen, who had snuck Widener into his hotel room on the sixth floor.

From there, Weidner began photographing the tanks driving along the road below, occasionally hearing the sound of bells signaling carts carrying bodies passing by or wounded being taken to hospital.

Other journalists were at the hotel too, including Jonathan Shah, a US-based CNN cameraman who had flown to Beijing to back up his exhausted colleagues, and who had set up a camera on the balcony of a CNN hotel room, from where the network aired live reports of the crackdown throughout the weekend.

“Another cameraman said, ‘Hey, look at that guy in front of the tank!’ so we zoomed in and started taking video,” Shah recalled.

“When the formation stopped and a guy blocked a tank, they shot over the guy’s head to try and scare him off. So it was basically our position to shoot over the guy’s head. The bullets were very close and you could hear them flying faintly.”

Back at Martsen’s apartment, Weidner was at the window preparing to shoot a line of tanks coming down the road, when “a guy with a shopping bag came forward and started shaking the bag,” he said. “I just focused on him, waiting for him to get shot.”

Jeff Widener/AP

Jeff Widener’s iconic “Tank Man” photograph shows an unidentified man standing in front of a line of tanks following the crackdown on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China on June 5, 1989.

The tank stopped and tried to go around the man, who then moved with the tank, blocking its path again. During the standoff, the man climbed into the lead tank and appeared to address someone inside.

But Widener had a problem: The scene was too far away for his 400mm lens. With a 2x zoom doubler lying on his bed, he was left with a choice: Go grab the doubler and risk losing precious seconds of shot?

Seizing the opportunity, he attached a doubler to his camera and “took one, two, three shots, and that was it,” he says. “Some people came, grabbed the guy and ran off. I remember sitting on a little sofa next to the window and the student (Maatsen) said, ‘Did you get it? Did you get it?’ Somewhere in my mind I had a feeling that maybe I did, but I wasn’t sure.”

Liu remembers getting a call from Widener University and issuing immediate instructions: Wind up the film, go to the lobby, and ask one of the many international students there to bring it to the AP office.

The photos were immediately sent across telephone lines around the world.

Widener did so, and the student rode off on his bicycle with the film hidden in his underwear. Forty-five minutes later, “An American guy with a ponytail and a backpack showed up with an AP envelope,” Liu says. They quickly developed the film, and “I saw the frame, and that was it. It was gone.”

Jeff Widener/AP

Student protesters stand in front of a burning armored personnel carrier that rammed into a line of students during an attack on pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square in Beijing on June 4, 1989, injuring many.

Shah, the CNN photojournalist, didn’t initially understand what was on the tapes. It was the early days of email and they couldn’t handle large amounts of video. So CNN used “equipment that could transmit video… a prototype that Sony gave us to try out,” but it took an hour to scan one frame of video and send it over phone lines, Shah said.

So they sent five frames, made a copy of the tape and sent it to the airport in Beijing, where they hired a tourist to take the tape to Hong Kong, which was then still a British colony and not under Chinese control.

Several media outlets photographed the “Tank Man,” but Widener’s photo was the most widely used, appearing on the front pages of newspapers around the world and being nominated for a Pulitzer Prize that year.

Widener said he had no idea the photo had generated such a strong response until he went to the Associated Press office the next morning and found messages from viewers and journalists around the world.

To this day, we don’t know who the man was or what happened to him, but he remains a powerful symbol of individuality standing up to state power.

“I think for a lot of people, this is personal because this guy symbolizes everything we struggle with in life. We’re all struggling with something,” Widener said. “He’s really become a symbol for a lot of people.”