According to Dawn newspaper, on May 29, a few miscreants used kerosene to set fire to a girls’ school in Ramzak tehsil of North Waziristan district in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, destroying furniture, computers, books and other items inside the school.

That same month, two girls’ schools in South Waziristan and Balochistan were targeted in attacks, while two girls’ schools in the Mir Ali area of North Waziristan were similarly bombed in May last year.

Why has there been such a recent spate of attacks, particularly in Two Waziristans, which border Afghanistan and were once the stronghold of the Pakistani Taliban (TTP)?

Resurrected TTPs

These attacks, which did not result in any casualties, were carried out by unidentified men and no responsibility was claimed, but it is clear that militants affiliated with the TTP are responsible. The TTP is an ideological offshoot of the Afghan Taliban and maintains its own organizational structure and set of objectives.

When the group first emerged in the early 2000s and officially came into being in December 2007, one of the first signs of its Talibanization in Pakistan was threats and attacks on school-going girls and working women who were perceived to be violating the extremists’ strict interpretation of Sharia (Islamic law). Educational institutions were then targeted because the Pakistani army was using them as barracks and bases for military purposes.

As attacks on girls’ schools intensify, the international community may recall the terrorist acts perpetrated by the TTP against Pakistan’s education sector, particularly the Army Public School, the Peshawar massacre in 2014, and the shooting of Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai in 2012. Counterterrorism operations such as Zarb-e-Azb (2014) and Radd-ul-Fasaad (2017) have significantly weakened the TTP and led to a decline in reported incidents of violence against schools.

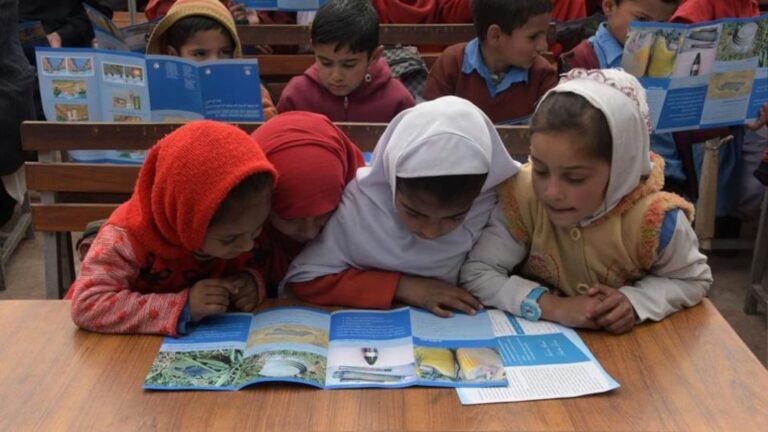

Emboldened by the Afghan Taliban’s capture of Kabul in 2021, the TTP has embarked on a revival path, attempting to emulate its predecessor’s practice of effectively banning women from receiving secondary education or higher. Now in its third year in power, and despite being condemned by the international community for its discriminatory policies against women, the Afghan Taliban does not seem to be willing to change its attitude. Thus, these attacks are undoubtedly a knock-on effect of the Afghan Taliban’s regressive policies in the border areas with Afghanistan, with immense implications for Pakistani society, which continues to struggle with other barriers to education.

“Education emergency”

Around the time of the first explosion in May this year, President Shehbaz Sharif declared a “state of emergency in education” and renewed his commitment to getting the roughly 26 million out-of-school children back to school, a move he calls “criminal negligence.” But even for those who are in school, the quality of the education provided remains poor, due to a lack of basic facilities such as water, toilets, boundary walls and, in many cases, qualified teachers.

Following successful results in Punjab during his tenure, Prime Minister Sharif has sought to set up his own “Daanish schools” – welfare schools – in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (known as Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan), Balochistan and remote areas of Sindh to provide education to the lower classes of society. In April, he inaugurated Islamabad’s first Daanish school, saying the dream of Pakistan’s founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, would not be realised without such education efforts.

The rhetoric on strengthening the education sector has been a notable aspect of Sharif’s tenure. He has promised that the federal government will bear the entire cost of these schools, despite the 18th Amendment to the Constitution making education a “provincial matter”. The scope of this amendment became a point of contention recently when the Special Investment Promotion Council (SIFC), a coalition of civilian and military leaders to save Pakistan from a severe economic crisis, convened a meeting to consider a new education policy. In response, a former chairman of Pakistan’s Senate criticised the move as an “infringement of provincial autonomy”, citing the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and saying it is outside the federal government’s jurisdiction to address the issue.

In any case, the key point here is that the broad-based reforms needed in Pakistan’s education sector will require sustained intervention that will require coordination between provincial and federal governments while adhering to the constitutional framework.

First, Pakistan needs to increase the share of education in GDP to the oft-cited 4%. Currently, Pakistan spends less than 2% of its GDP on education. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2022-23, the overall literacy rate is just over 62%, with 73.4% for men and 51.9% for women. Therefore, to bridge the literacy gap between men and women, especially in the tribal areas bordering Afghanistan, Pakistan could take the help of religious scholars to launch an awareness campaign highlighting the importance of girls’ education and encouraging parents to assure them of their safety. Otherwise, it would unintentionally entrench the power of extremists in the region who would rather not send girls to school.

More importantly, ensuring access to education is provided to all, without which children risk becoming a breeding ground for future recruitment into extremist networks and may be forced to turn to madrassas, which offer free schooling and accommodation but have historically been seen as hotbeds of radicalisation.

As Pakistan fights to reverse a new wave of militancy, prioritizing education will not only be an effective bulwark against extremism but will also move the country forward on many fronts, including achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4, which states, “Ensure inclusive, equitable and quality education for all.” Pakistan committed to this when it passed a unanimous resolution in 2016 to endorse the SDGs as part of its national development agenda.

Vanthirani Patro is a Research Scientist at the Centre for Aerodynamic Research, New Delhi. Views expressed here are personal.