As legal experts debated Thursday how the courts might approach Louisiana’s law, various religious leaders in the state expressed excitement and concern about what the Ten Commandments measure means.

Lawyers from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Americans for Separation of Church and State and the American Civil Liberties Union said they plan to file a lawsuit against the new law next week.

“While it’s true that the current Supreme Court has not done its best to resolve church and state issues, we believe this is an overreach,” said Heather Weaver, an attorney with the ACLU’s Religion and Belief Freedom Program. “Nothing in the Court’s words suggests that the Ten Commandments should be allowed in classrooms where students are held and required to attend.”

Some outside experts on church and state law are less convinced.

“We’re in some ways entering uncharted territory right now,” said Michael Helfand, a professor of religion and ethics at Pepperdine University School of Law.

With the Supreme Court siding with those seeking to relax religious regulations, efforts to infiltrate religion into government institutions, including public schools, have grown in the past decade. State lawmakers, particularly in conservative districts, have introduced hundreds of bills aimed at adding everything from chaplains to school entrances, to “In God We Trust” signs, to public funding for religious schools through vouchers.

The Louisiana law is part of a series of new measures resulting from a 2022 Supreme Court ruling in favor of a high school football coach whose contract was not renewed for praying at the 50-yard line after a game. Kennedy v. Bremerton School District It abolished the standard that had been used for more than 50 years to determine whether a law violated the First Amendment’s separation of church and state clause.

The Lemon Test, named after a 1971 Supreme Court decision, asked questions such as: “Does the law cause ‘undue government involvement with religion’?” and “Does the law promote or hinder religion?” In the football coach case, the Supreme Court said the Lemon Test was no longer valid law and that judges should look instead at “history and tradition.”

It should be noted that, Bremerton While the ruling found the coach’s actions constitutional, the ACLU’s Weaver said its reasoning differs from Louisiana law. Because the court said his prayers were not “public” or delivered to a “captive” audience.

“Regardless of the Lemon test, there has always been an understanding in this country that the government cannot favor one denomination or religion over another. Here, not only do states mandate the Ten Commandments, but the statutes state which version and state the wording,” Weaver said.

The law requires the use of a Protestant-specific Bible based on the King James Version, which is different from the version used by Catholics, Jews, and others, let alone other religions with their own faith documents.

Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-executive director of Freedom from Religion, said the new law “goes too far.”

“The Religious Right, Christian nationalists and their legal organizations Bremerton “The idea is that this decision overturns all precedent against religion in public schools, but that’s not the case,” she said. “The Supreme Court is in the hands of the Trump administration, and I hope they’re not going to go that far.”

“A lot of ignorant people may think there are Ten Commandments in the Constitution, but there are no Ten Commandments in the founding history of our country,” she said, calling the law “the antithesis of the Bill of Rights.”

Pepperdine’s Helfand said it’s true that America’s Founding Fathers cited the Bible and the Ten Commandments when founding the country, but they still wanted people to be able to worship or not worship as they please. The legal debate may now shift to the issue of coercion, he said. When is it acceptable to be coerced into a religion you don’t believe in? Does that include seeing the Ten Commandments posted on the wall of a classroom?

“You still can’t prioritize one religion over another,” Helfand said.

John Inazu, an expert on religion and law at Washington University in St. Louis, noted that the Supreme Court’s 1980 strikedown of a similar law was based on a different legal approach. Inazu wrote in an email that the earlier case “was decided based on a very different approach to the separation of church and state clause. The Supreme Court has since moved to focus more on history, text, and tradition. But I’m not sure that Louisiana’s law would survive under the new framework.”

Bringing this version of the Ten Commandments into the classroom, rather than a long-standing memorial or tradition, is “overtly religious and monotheistic,” Inatsu wrote.

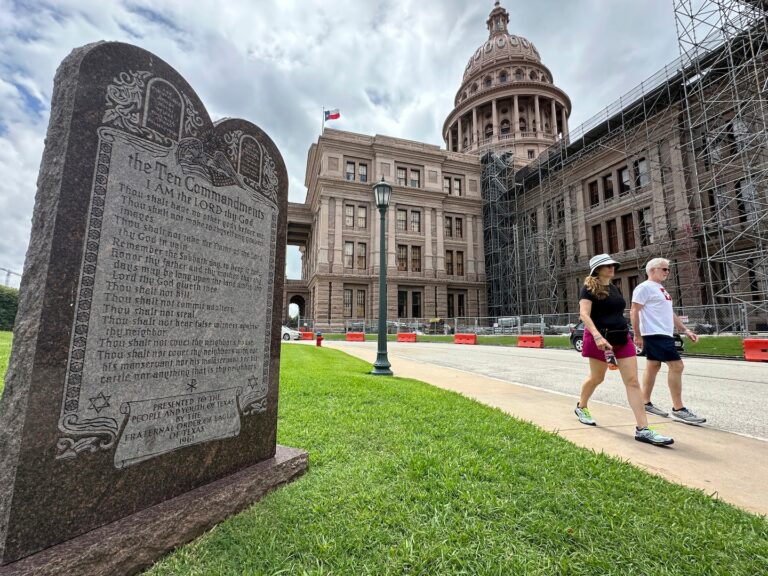

He noted that the Supreme Court upheld a Ten Commandments monument on the Texas Capitol grounds in Austin in 2005. But he said the monument is separate from the Capitol itself and includes the U.S. flag, a Star of David and the coat of arms of the civic group that donated it. The court said the monument has a secular purpose and does not imply government endorsement of religion.

After the commotion,Bremerton The bill, which aims to promote religion in public schools, was an attempt by Texas last year to approve a Louisiana-style Ten Commandments bill. The bill passed the state Senate but was not taken up in the House. But supporters of the bill represented a voice for Americans who see the Supreme Court as ready to set the country on the right track after a half-century of misguided separation of church and state.

“There is absolutely no separation of God and government, and that’s what this bill is about. That’s the misconception. That’s not reality,” Sen. Mays Middleton, R-Texas, a co-sponsor of the bill, said last year.

One of the authors of the Louisiana law said the bill isn’t just about religion, nor are the Ten Commandments.

“It’s our fundamental law. Our sense of right and wrong is based on the Ten Commandments,” state Assemblyman Michael Bayham (R-Washington) told The Washington Post, saying he believes Moses was a historical figure, not just a religious figure.

Opponents of the new bill say it reflects the current state of the country. The balance between church and state has reached a dangerous new level, with those in power in some places To assert the superiority of Christianity.

“Look, I love Jesus and the Bible, but this is not right. Cheers to Los Angeles looking like a fool on a national stage,” the Rev. Michael Alero, a Catholic priest in Baton Rouge, posted Wednesday on X. “How much taxpayer money will be wasted defending this in court only to have it overturned?”

But Tony Spell, a Pentecostal pastor from Baton Rouge, said the new law is an extension of a 2022 victory he won when he fought pandemic restrictions in the Louisiana Supreme Court, which had dismissed charges against Spell for leading a religious gathering despite lockdown orders.

“We have a conservative court in Washington,” Spell said, “but really, this is about the people, the warriors, the fighters.”

Since the court battle, he said, the movement to incorporate Christianity into all parts of life has only grown, and he’s now working with a group that’s raising funds to have Ten Commandments posters soon on display in classrooms across the state.

When asked what the new law means for people who are not Christians or don’t believe in their version of the Ten Commandments, Spell said, “Being offended is a choice.”

Mark Chancey, a professor at Southern Methodist University who studies the use of the Bible in public schools, said the Supreme Court has led the country into a new era.

“It’s truly a lawless area when it comes to government-sponsored religion,” he said, adding: “It’s unclear how all of this will play out.”