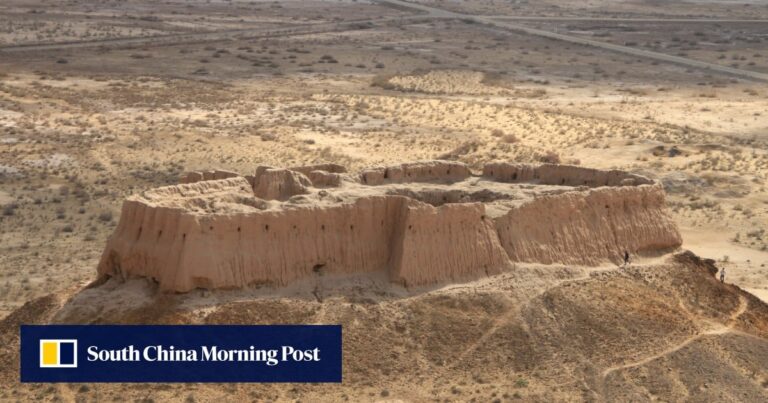

Chinese and Uzbek archaeologists have completed the first phase of a joint project to unearth ruins of ancient empires along the Silk Road.

Excavations in the Surshandario region of southern Uzbekistan have uncovered a “significant number” of artefacts and dozens of burial sites from the Kushan Empire, an important Silk Road outpost, according to China’s state news agency Xinhua.

Archaeologists believe the find, which also included three houses, shows that eastern Suršandarya was “a region of great importance for the distribution of the Kushan people.”

Little archaeological research has been done in the area, and the team said their work helped to add to the historical record.

“The continued presence of traces of habitation in the eastern part of the Surshandarya River basin during the Kushan period fills a gap in the history of this period in the region,” the Chinese team told Xinhua.

The Kushan Empire, which emerged in the 1st century AD, controlled much of present-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, as well as parts of India and Iran, and became an important base on the Silk Road.

The empire is also thought to have played a key role in helping to spread Buddhism, with some historians believing it was the route by which Buddhism first reached China during the Han dynasty.

The excavation is one of a number of projects China is undertaking to strengthen cultural ties with Central Asian countries, with the China Institute of Archaeology, Shaanxi Provincial Archaeological Institute and Northwestern University playing leading roles.

The first joint project with Uzbekistan began in 2012, which Chinese state media described at the time as an effort to “study the civilization process of ancient cities and the cultural lineage and route of the ancient Silk Road.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping has repeatedly emphasized the importance of these efforts during his visit to Uzbekistan in 2016 and when he hosted the first China-Central Asia Summit last year, bringing together the leaders of five countries.

He told visitors it was important to “inherit traditional friendly relations and promote exchanges between people” and promised to boost cultural tourism.

The term Silk Road was coined by 19th-century German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen to describe the trade network through which precious goods such as silk, porcelain, jade, gunpowder, livestock and fruit were traded in a vast network linking the major Eurasian empires.

The route’s centre was Central Asia, a crossroads for traders travelling between China, Persia, India and the Roman Empire.

Zhu Yongbiao, a professor of international relations at Lanzhou University, said China wants to promote joint archaeological projects to enhance cultural and people-to-people exchanges, which could lead to promoting the Belt and Road Initiative, a modern infrastructure project based on the ancient Silk Road.

“The promotion of the Belt and Road Initiative requires exchanges between people, and archaeological cooperation is one of the key areas,” Zhu said.

Meanwhile, Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries are rediscovering their own history after decades of assimilation and oppression by the Russian-controlled Soviet Union.

He said independence had stimulated “a strong interest in history and national origins”, adding that this was “a stage that every country has to go through after independence”.