This column was originally published In the middle, A weekly newsletter with everything you need to know about transportation in and around New York City.

sign up To receive the full edition, including answers to reader questions, trivia, service changes and more, emailed to you every Thursday, click here.

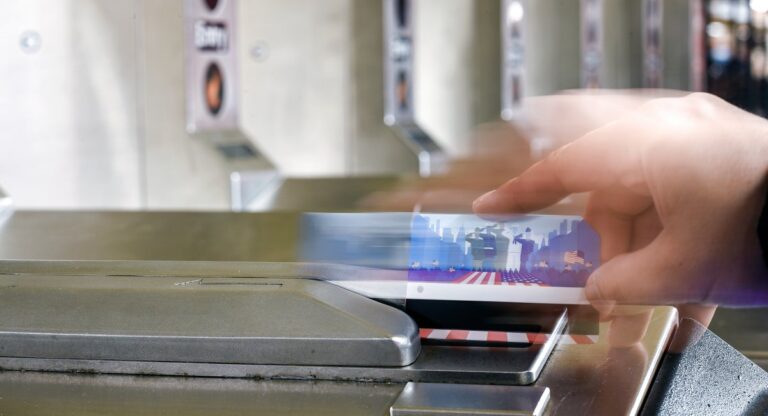

The MTA is taking a new tactic in its fight against fare evasion: persuading New York City students to pay their fares.

Last weekend, I had the opportunity to interview outgoing New York City Transportation Commissioner Richard Davie. Our conversation was mostly about the $15 billion hole in the MTA budget caused by Governor Kathy Hawkle’s moratorium on congestion pricing. But Davie also shared an interesting observation about unfair fare hikes: fares tend to spike around 3 p.m. when school gets out.

“Actually, this isn’t fare evasion because these kids already have prepaid cards. They don’t want to use their cards for whatever reason so we may be seeing a little bit more fare evasion as a result,” Davey said.

So I thought: Maybe students who have MetroCards but can’t be bothered to swipe them are partly responsible for the MTA’s so-called “existential threat” to fare nonpayment?

As a father of two, I can say with certainty that many kids never bother to swipe a free student MetroCard. My son lost his MetroCard and can’t be bothered to get a replacement. My daughter tries to use hers but it’s so crumpled it no longer works.

That’s where the MTA’s Extra Credit campaign comes in, an attempt to sell students on the benefits of a MetroCard (or, later this year, a free OMNY card). Last month, the agency began giving away a free virtual reality Meta Quest 2 headset each week to one random high school student who used a student MetroCard and earned perfect attendance that week.

“Our hope is to create buzz around swiping and encourage regular use,” Chantel Cabrera, senior director of subway coordination and solutions, said at an MTA board meeting last month. “We want to put in place a comprehensive approach to promote fare compliance that will appeal to young people.”

Cabrera’s comments may seem like a “hey guys” kind of thing, but they’re actually dangerous. According to MTA data, fare nonpayment continues to rise, with 13.6% of subway riders not paying their fares and nearly half of bus riders not paying their fares. The MTA expects to lose $285 million from nonpayment of subway fares and $315 million from nonpayment of bus fares this year. It’s unclear how many of those who do not pay are students. But MTA Chairman Jano Lieber has suggested he believes students are among those illegally passing through turnstiles.

“They have student MetroCards in their pockets, which means they lack the education and culture to understand what fare evasion means,” Lieber said. “They’re part of New York and we’re going to address that problem. We need them to play by the same rules as everyone else.”

Curious commuters

Question from Martin from Brooklyn

Why do the trains run so slowly sometimes? Some days it feels like an amusement park monorail, but other days it’s normal. I usually take the B or Q from Brooklyn to Manhattan or Manhattan to Brooklyn.

Clayton’s statement

There are two main reasons subway trains move slowly along the tracks: traffic jams and track work. According to rail operators we spoke to, subway tracks on some lines tend to get clogged during rush hour, slowing down the entire system. But the “funfair-park monorail” speeds Martin feels are mostly due to track maintenance and construction work. When workers are on the roadbed, subway operators are typically prohibited from running trains faster than 10 mph, even if the train is running on the tracks adjacent to the workers. Trains can move even slower if workers have to “clear,” meaning they need to get into the space right next to the tracks to allow the train to pass a work site.

Have a question? Curious Commuter Questions is exclusive to On The Way newsletter subscribers. Register for free here Check Thursday’s newsletter for a link to submit your question.