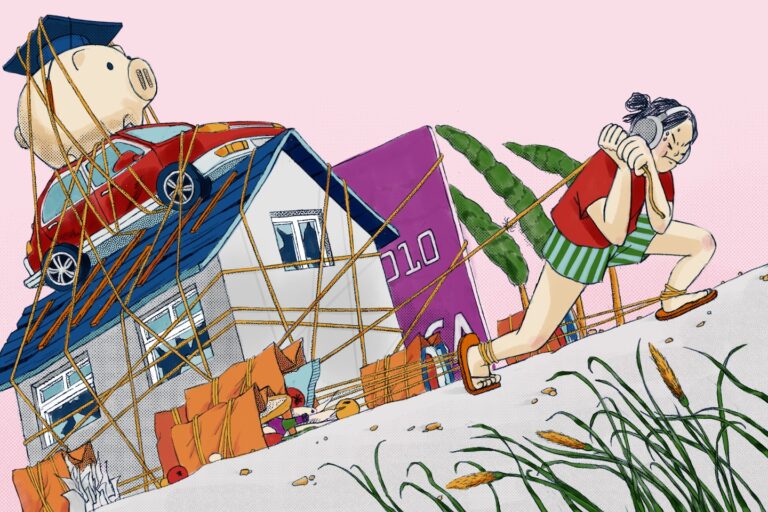

So far, Gen Z workers are more likely than millennials to have attended college, held jobs, and earned more. But they also pay 31% more for housing than their peers a decade ago, after adjusting for inflation. Spending on auto insurance for people ages 16-24 more than doubled between 2012 and 2022, and spending on health insurance for this age group is up 46% after adjusting for inflation, according to BLS data.

By comparison, inflation-adjusted incomes for this generation have grown just 26% over the same period, federal data shows.

“Generation Z consumers have been hit hardest by the pandemic and its aftermath on their finances, even more so than the challenges millennials faced as a result of the global financial crisis,” said Michelle Ranelli, head of U.S. research at TransUnion. “While both generations have emerged from difficult economic times, Gen Z is struggling even more to cover new living expenses.”

The economic hardships plaguing Gen Z may help explain why President Biden is struggling to connect with younger voters who cite inflation as their top concern. According to a University of Chicago GenForward poll, in May only 32% of voters under 30 said they would support Biden if the election were held today, putting him two points ahead of Donald Trump.

Compared to millennials of the same age, Gen Z has more debt of all kinds, including credit cards, auto loans and mortgages, after adjusting for inflation, according to TransUnion’s internal records. Credit reporting agencies have found that today’s 22- to 24-year-olds are more likely to default on credit card and auto payments than previous generations.

And Gen Z’s debt is growing faster than their incomes., Gen Z’s debt was equivalent to about 16% of their income at the end of last year, up from 12% for millennials a decade ago, according to a TransUnion survey.

Sarah Martin, 21, of Pittsburgh, began racking up credit card debt a few years ago on impulse purchases of clothes, makeup, and other items after pandemic restrictions were finally lifted. A dental emergency caused things to spiral out of control, maxing out one credit card and nearly maxing out another. In total, Martin owed about $8,000 and is still working to pay it off.

Financial hardships are inevitable, she said: Martin was in elementary school during the Great Recession, when her parents lost their jobs and then their home. Now, as a young adult, she’s facing similar financial challenges and feeling anxious about her future.

“I grew up in financial turmoil and it feels like it’s always been that way,” said Martin, who lives with her parents while studying to become a medical coder. “With high interest rates, it feels like you’re always on the hook for debt repayments, but you’re never going to be able to pay them off.”

Roughly one in seven Gen Zers has maxed out their credit cards, more than any other generation, according to the New York Fed, and the ripple effects of that debt are much greater than in the past, with average credit card interest rates now at an all-time high of nearly 22%.

“Even when accounting for inflation, the balances on these credit cards are [among Americans in their early 20s] “It’s up about 25 percent. Young people are delinquent at higher rates than they’ve ever been in the past,” says Ted Rothman, a credit card analyst at Bankrate. “When you’re just starting out and you’re already behind, it’s hard to break that cycle.”

Timing also matters, economists say: The pandemic forced Gen Z to stay home during the prime of their high school and college years, when they would have been hanging out with friends, going to concerts, and traveling. When the world reopened in 2021, many were eager to make up for lost time.

It was also around this time that banks began to loosen credit card eligibility requirements, making cards more accessible to even the youngest borrowers.

Thomas Black got his first credit card when he turned 18 in 2021 and quickly maxed it out, spending about $1,000 on gas and Christmas gifts before his car broke down and he found himself thousands more in debt.

“I spent the first three years of my adult life paying off debt,” said Black, who works for a security company in Akron, Ohio. “I worked 84-hour weeks, taking on as much overtime as I could to pay off my debt.”

Gen Z is coming of age at a very different time than millennials, whose early years in the workforce coincided with two recessions. Many struggled to find work, especially after the Great Recession, when the national unemployment rate hovered around 10% for more than a year. Their wages also took a big hit. According to economist Kevin Linz, millennials lost about 13% of their income on average between 2007 and 2017.

In contrast, the recovery since the pandemic has been swift and broad-based. Unemployment rates are Through May, wages were trading at less than 4% for the longest time in 50 years, with younger workers seeing the highest growth: Wages for 16-24 year olds rose 8.6% in the past year, compared with 5.2% overall, according to the Atlanta Fed.

Still, rising prices are hitting Gen Z hard: Compared to other age groups, adults under 27 spend more on basics like housing, dining out, gas, and car insurance — all of which have risen significantly in price in recent years, according to Moody’s data.

“We are at a tipping point. [Gen Z is] “They’re coming of age in a time of rising inflation and interest rates, and that’s going to stick with them,” said Jimmy Lentz, a professor of finance and economics at Duke University who studies generational behavior. “There will be immediate effects, like higher monthly credit card payments, but there will also be longer-term effects, like it becoming harder to buy a home.”

Housing costs, which have risen sharply since the pandemic, have so far been the biggest burden on Gen Z. Adults under 35 are more likely to rent than own a home and tend to move more frequently, both of which can increase the frequency of price increases.

Overall, Gen Zers can expect to spend an average of $145,000 on rent by the time they turn 30 — well above the $126,000 spent by millennials at the same age, when inflation is taken into account. Census data via RentCafe. Rent costs in major coastal centers like the San Francisco Bay Area, Boston, and Honolulu are especially high for today’s young people.

In Birmingham, In Alabama, the rent for the apartment where Edward Wyckoff, 25, lives with his mother has jumped from $900 to $1,300 in the past few years, a 44 percent increase.

Wyckoff was a sophomore when the pandemic began and put her studies on hold to help her family make ends meet, but she says it’s becoming harder to finish her degree. She already owes $18,500 in student loans and worries about falling further into debt.

“I have this idea that debt is a trap,” he says. “Everyone I know seems to be drowning in debt.”

Wyckoff hopes to go back to school and is working a variety of jobs, including driving a snow cone truck and working as an assistant in a law firm, to save up money and apply for scholarships and grants to help ease the financial burden.

“The cost of everything is so high that it’s forced me to work more than I thought I would,” he says. “I thought I could manage if I combined school and work, but now I have to choose my job. It feels like a dead end, especially since I already have student loans to pay off.”

Gen Z is not only more likely to have student loan debt, but they also have higher debt balances than millennials, according to the St. Louis Fed: As of June 2022, the average student loan debt for borrowers ages 20 to 25 was about $21,000, which, when adjusted for inflation, is 13% more than millennials of the same age.

They are also the first generation to have a higher unemployment rate than the general population, and according to the New York Fed, in a stark reversal of long-held belief that recent college graduates are having a harder time finding work than other generations.

Spencer Kammerman graduated from the University of California, Irvine with a degree in computer science and engineering three years ago. Since then, the 25-year-old has worked at two technology companies: I was fired from both.

His latest unemployment streak began eight months ago, when he applied for hundreds of jobs and was a finalist multiple times, including for SpaceX and a government drone contractor, only to lose out to other candidates.

Kammerman, who ran out of unemployment benefits several months ago, recently moved back in with her parents in Orange County.

“I feel like the odds are stacked against me,” he said. “It’s been hard to get the business going, but I’m not giving up.”

Andrew Van Dam contributed to this report.