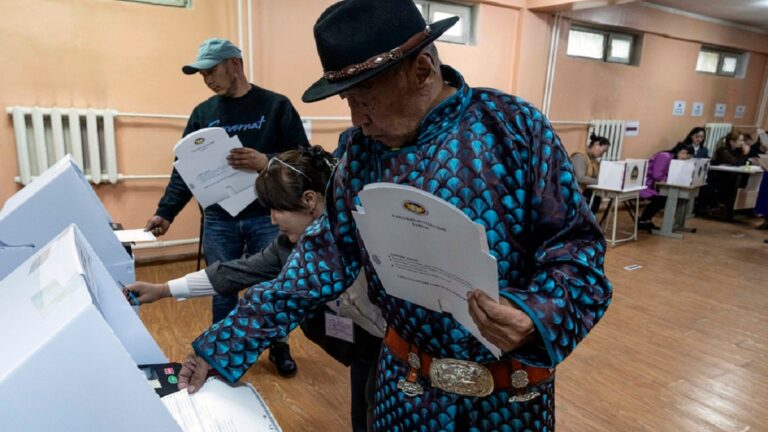

A Mongolian man puts his ballot into a counting machine at a polling station in a ger district on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. AP

Mongolia is voting for its next government today (June 28). The sparsely populated, landlocked Asian country lives in the shadows of two much larger autocracies: China and Russia.

The country’s nomadic people were once extremely ferocious and feared by many. At one point, their bravest people conquered China and expanded westward across Asia to the edge of Europe. As of 2022, only 3.4 million people in this democratic nation live below the poverty line, according to the Asian Development Bank.

The country’s vast mineral wealth, sought after by China and the West, is driving global decarbonization, but it remains dependent on dirty coal, which contributes to some of the world’s worst air pollution. Nomadic livestock farming is vital to the country, but millions of animals have been lost to extreme weather exacerbated by climate change.

What is a Dzud?

Dzud is the Mongolian word for disaster. These extreme weather events, which once occurred once every 10 years, have become more severe and frequent as global warming progresses. The combination of years of drought and harsh, snowy winters has devastated livestock.

Livestock farming is central to Mongolia’s economy and culture, accounting for 80 percent of agricultural production and 11 percent of GDP. The impact of the dzud has been devastating. This year’s dzud was the sixth in the past decade and the worst on record, with more than 7.1 million animals killed. Thousands of families lost more than 70 percent of their entire livestock.

What is the state of the mining industry in the country?

Mongolia derives almost a quarter of its GDP and about 90 percent of its exports from mining. The Oyu Tolgoi mine in the Gobi Desert in the south of the country is known to be one of the world’s largest deposits of copper and gold. Some in Mongolia hope that growing demand for so-called critical minerals will give the country an edge over its larger neighbors as it seeks to decarbonize.

But Mongolia has struggled to share the benefits and costs of its mineral wealth. Nomads, who make up a third of the population, denounce the loss of pastures and alleged land grabbing. Mass protests erupted in Mongolia in 2022 over allegations of corruption in the mining sector.

Why does the election matter here?

After six decades of communist rule, protests in 1990 sparked a shift to democratization. Inflated hopes that democracy would bring prosperity and solve all the country’s problems have succumbed to reality. As voters elect a new parliament this week, many are increasingly frustrated with a system they see as riddled with corruption and biased toward mining and other business interests over ordinary people.

Voters will be choosing a larger parliament, with 126 seats, up 50 from the last election. The ruling Mongolian People’s Party is likely to win, but its current overwhelming majority may lose some seats. The MPP ran the country during communism but is now a centrist left-wing party.

Why is air pollution so bad in Mongolia?

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital, has some of the worst air quality in the world, with annual concentrations of inhalable particles known as PM2.5 nearly nine times what the World Health Organization considers safe. Children are particularly at risk.

Climate shocks like dzud are forcing more and more people to move to cities, living in traditional tents called “gers” and burning coal or wood for heat during the country’s harsh winters, adding to the smog produced by Mongolia’s coal-fired power plants and diesel vehicles.

What is the history of Mongolia?

National hero Genghis Khan rose to power and became leader of Mongolia in the early 13th century, then began conquering lands to the south and west. His descendants, known as Genghis Khan in Mongolian, conquered China and ruled it for nearly a century as the Yuan Dynasty.

In the 20th century, Mongolia sought independence from China and received assistance from the Soviet Union, which helped improve public health and education, but at the same time turned Mongolia into a de facto satellite state, and Mongolian traditional culture came under the influence of Russian communism.

Since Mongolia gained full autonomy and transitioned to democracy, Genghis Khan has been a linchpin in efforts to reclaim the nation’s heritage, with his image appearing everywhere, from vodka bottles to a 40-metre-tall stainless steel statue of him on horseback outside Ulaanbaatar.

Input from AP

Find us on YouTube

subscribe