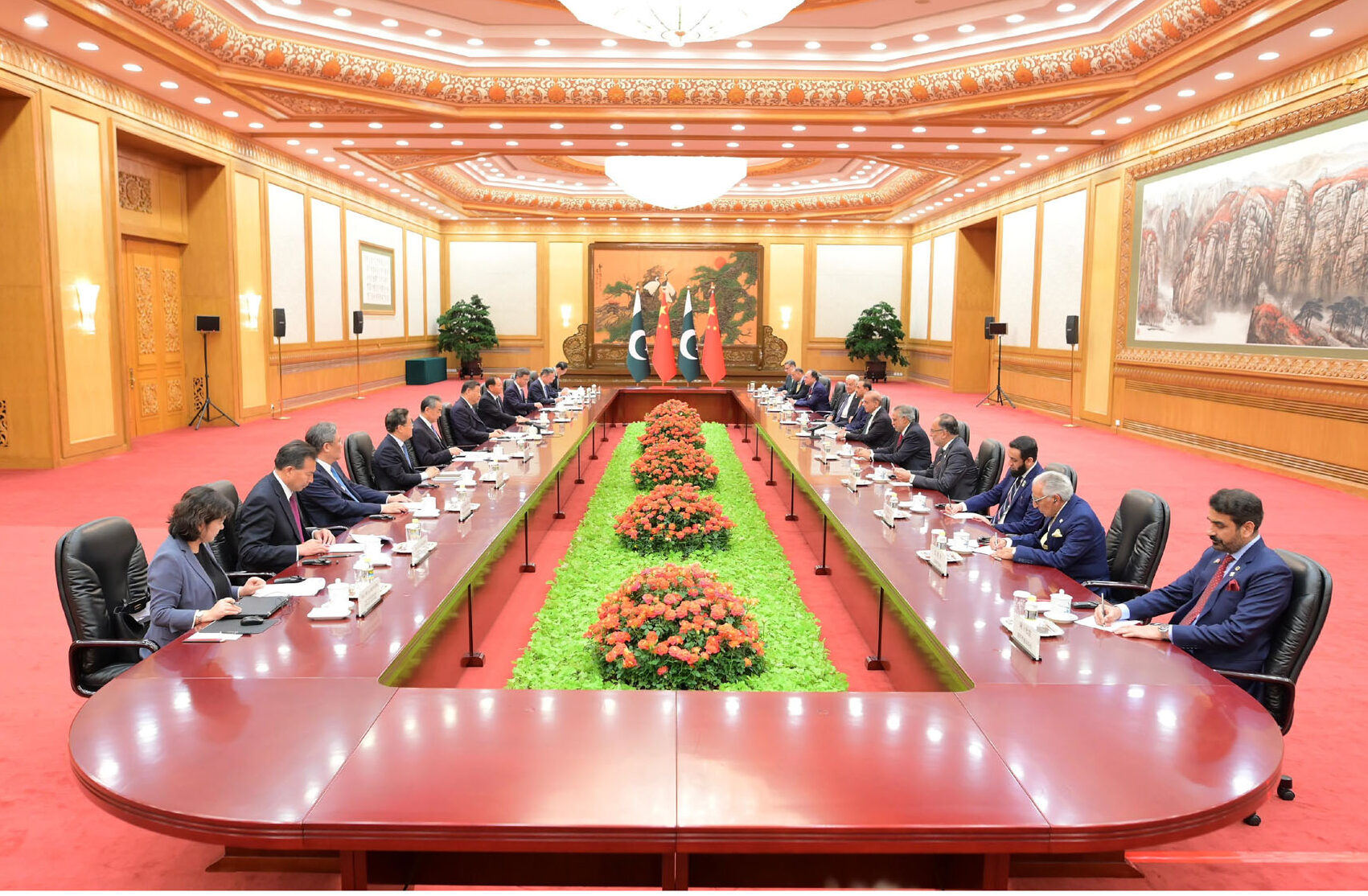

Pakistani Prime Minister Sharif met with President Xi Jinping and other Chinese officials earlier this month but returned home with almost nothing. China did not commit to investing in Pakistan’s big projects with any clear timeline. The only public outcome of the meeting was a few memorandums of understanding (MOUs) signed between the two sides and typical Chinese assurances. There are various views on the visit, but it certainly did not meet Pakistan’s expectations of Chinese assistance in this time of economic crisis. This cold response may indicate that China’s enthusiasm for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which has seen an upswing in recent years, is fading. Delays in payments, political instability and security issues in Pakistan seem to have led the Chinese leadership to believe that Pakistan, their all-weather friend, needs major policy reforms to qualify for the next round of investments. Therefore, unless dramatic reforms are made, Islamabad should keep its expectations of Beijing low.

A less than stimulating work relationship

Beijing and Islamabad’s experience over CPEC, launched in 2013, did not inspire confidence in future Chinese infrastructure investments in the country. Touted as the flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), CPEC has been plagued by unexpected delays since its inception. The first phase of CPEC was completed in record time as Chinese companies led the construction process as in most cases of BRI projects. However, the so-called second phase began to slow down in 2019 as the Pakistani side failed to meet deadlines. Despite an agreement between the two sides to speed up the process, several large projects remain incomplete. Notable among the delayed projects are the Chinese-model Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in all provinces and the federal capital, and the Karachi to Peshawar railway line (ML-1), which China declared a strategic project in 2017.

This political instability and infighting exacerbates the bureaucratic confusion and incompetence that are impeding progress on China’s infrastructure investment.

The delays on the Pakistani side were due to a combination of poor economic decision-making and environmental factors. A series of misfortunes in Pakistan further delayed already questionable payment arrangements. The country experienced a severe balance of payments crisis from 2017 to 2023, and the COVID-19 pandemic adversely affected the economy and stalled CPEC projects. Moreover, Pakistan suffered its worst floods in recent history in 2022. Payments to Chinese independent power producers (IPPs) suffered as the country’s leadership had already over-promised. Over the past three years, Chinese IPPs had frequently complained about payment delays.

Domestic political instability

The second major issue influencing Beijing’s lukewarm response to Islamabad’s requests is Pakistan’s political instability. Since the CPEC project began, Chinese officials and business have been negotiating with four Pakistani governments, all of which have been mired in protest, unrest and uncertainty. Protests against the governments postponed President Xi Jinping’s visit to Pakistan in 2014 and paralyzed Islamabad for four months. The Chinese leadership has also been confronted with corruption allegations surrounding infrastructure projects, political tussles for local influence, friction among elites and public discourse over Pakistan’s concerns about CPEC, including fears that economic benefits are not being delivered to the Pakistani people.

This political instability and infighting have further exacerbated the bureaucratic disarray and incompetence that have stymied progress on Chinese infrastructure investment. The previous Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) government changed the agency responsible for implementing CPEC projects three times. The responsibility shifted from the Prime Minister’s Office to the Ministry of Planning and finally to the Board of Investment (BOI). During the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) era, it returned to the Ministry of Planning and finally settled with the newly established CPEC Authority, headed by a retired three-star general. Each change brought new faces, new policies and new ways of working. However, these changes did not have a positive impact on the progress of CPEC. Promises were not fulfilled and phrases such as “one-stop operations” suggesting stakeholders would go to one place to submit all the required documents and “revolving accounts” for automatic payments to Chinese investors remained mere phrases. Repayment arrangements remain fragile, sometimes forcing the intervention of the Prime Minister’s Office.

Security concerns exacerbate Chinese insecurity

Another factor that poses the biggest potential risk to Chinese investors is Pakistan’s unstable security environment and the rise in militant attacks targeting Chinese workers. Between the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021 and June 2023, terrorist attacks in Pakistan surged 73 percent and total casualties increased 138 percent. Two provinces, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), an artery connecting China with Pakistan, and Balochistan, home to the CPEC centerpiece Gwadar port, saw attacks soar 92 percent and 81 percent, respectively, over the past 22 months.

The Chinese leadership is rightly concerned about the safety of Chinese nationals working in Pakistan. According to one study, there were eight terrorist incidents targeting Chinese nationals in Pakistan between 2004 and 2010, but since 2011, the number of incidents targeting Chinese nationals has soared to 25. The intensity and geographical scope of these attacks have also increased. The surge in attacks has also come after Pakistan set up two special security forces and a naval task force to protect Pakistan’s CPEC and Chinese workers. Following other recent attacks, as well as an attack on March 24 that killed five Chinese workers in Shanla area of KP province, the president, prime minister and army commander have separately assured the Chinese authorities of the safety and security of their nationals. A recent China-Pakistan joint statement released by the Pakistani foreign ministry also underlines this point.

China officially wants to expand CPEC into Afghanistan and Iran, but the matter is complicated by Pakistan’s uneasy relations with its neighbors except China. In 2024, Pakistan exchanged fire with both Afghanistan and Iran. Tensions with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan remain particularly high.

This trend is bound to make Chinese investors uneasy. As long as Pakistan’s relations with its neighbors remain poor, the dividends from Chinese investment in CPEC construction will remain slim, as border tensions will negatively impact trade and thwart potential connectivity projects. Another concern for Chinese leadership is that without Taliban support to curb the threat of the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP), Chinese personnel and projects in Pakistan will face growing terrorist threats. China has been trying to improve relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan in 2023, but so far there has been little improvement.

Islamabad is doing all the right things in terms of messaging to Beijing, but Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership needs to conduct a policy review with an eye on long-term goals.

Can Pakistan save CPEC?

Prime Minister Sharif’s visit to China under difficult circumstances demonstrates his commitment to the project, but it also makes clear that there are limits to what Pakistan can expect from its relationship with China. Statements from the Prime Minister’s Office and policy decisions indicate that the Pakistani leadership is aware of these challenges. After all, for the past six months, the message from Beijing has been that without streamlined business activities, political stability and adequate security measures, nothing will change.

Islamabad has tried to show that it is working to improve all three dimensions to convey to Beijing that CPEC is a priority. On the economic front, the Pakistani government released billions of rupees to Chinese energy companies ahead of the Prime Minister’s visit to China. On June 21, the Chinese government held the third round of the Joint Consultative Mechanism, a forum for dialogue between the Chinese Communist Party and Pakistani political parties, suggesting to the coalition that it can work with other political stakeholders for CPEC. The meeting was attended by representatives of all major political parties and reaffirmed China-Pakistan bilateral cooperation and their commitment to CPEC. On the security front, Pakistan’s Supreme Committee (comprising civilian and military leaders) decided to launch a nationwide counter-terrorism operation, “Azm-e-Istekam (Resolve for Stability),” on June 22. It is not surprising that Pakistan announced this plan, coming after the Prime Minister’s visit to China and the visit of Chinese Communist Party members to Pakistan.

Islamabad is doing all the right things in its messaging to Beijing. But Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership needs to undertake a policy review with an eye on long-term goals. Pakistan already has an unremarkable history of projects and initiatives that are incomplete or delayed year after year. Without an economic charter with the backing of all mainstream political actors, zero tolerance towards extremism and radicalism, normalization of relations with neighbouring countries including India that would ensure peace on the border and help Islamabad channel its limited resources into constructive areas, and the political stability required for long-term planning and commitment, nothing substantial is likely to come from Beijing in the coming years. Till then, China-Pakistan economic relations will be subject to what can best be described as a “makeshift arrangement”.

***

Also read: Economic Outlook: Prospects of China-Pakistan air cargo connectivity

Image 1: Roads constructed by CPEC, Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif meets with President Xi Jinping on June 7, Ministry of Foreign Affairs