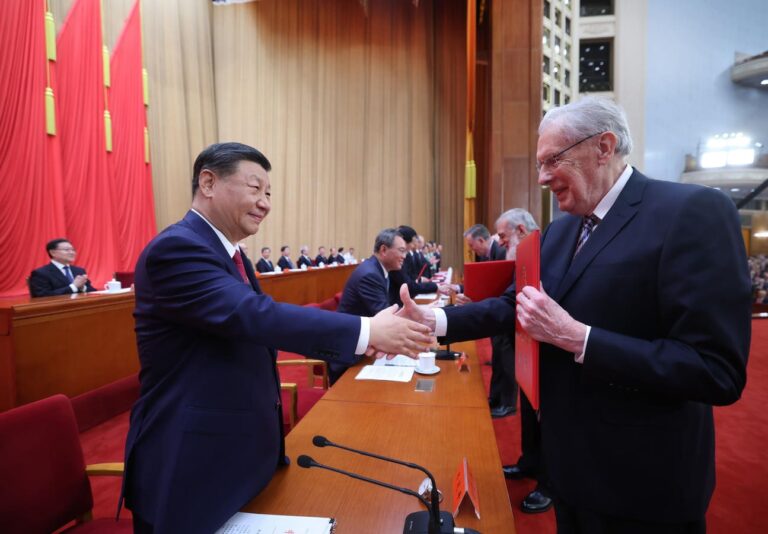

Xi Jinping and other leaders of the Chinese Communist Party and the state, as well as two … [+]

Recent developments highlight the shared interest of the United States and China in divvying up technological developments, an area that has long benefited from globalization.

Leaders in both Beijing and Washington have come to two conclusions. The first is simple: innovation is the best and only key to economic growth and geopolitical leadership. The second is that to gain scientific and technological advantage, countries must take strong measures in the public and private sectors to compete with (and differentiate from) others.

These dynamics existed before the rise of artificial intelligence, but AI’s now-ubiquitous importance has added a new dimension to the technology wars: the Chinese “threat” has combined with the “risks and opportunities” that AI poses to create opportunities for American technology companies to curry favor with their own government and, in the process, stifle AI capabilities in countries where their main competitors are based.

For example, Chinese media reported that OpenAI will take additional steps to restrict API traffic from countries where its services are not supported, such as China. Domestic competitors such as Zhipu AI are trying to fill the gap, but another U.S.-made restriction stands in their way: chip restrictions. This is because U.S. semiconductor export controls aimed at China would limit China’s access to the computing power that Chinese companies need to fully replace OpenAI.

The recent U.S. government actions are two separate and distinct do not have Comparable technological environments: one in the US, the other in China.

For example, on June 21, the Treasury Department released proposed rules to implement last year’s executive order, which restricts high-tech investments by Americans in China. According to Treasury Under Secretary for Investment Security Paul Rosen, “President Biden and Secretary Yellen are committed to taking clear and targeted steps to prevent countries of concern from advancing key technologies, such as artificial intelligence, that threaten U.S. national security.”

Specifically speaking about AI, the proposed rule proposes a “prohibition on covered transactions related to the development of AI systems that are designed or intended to be used exclusively for a specified end use.” This wordy language suggests military use, but its vagueness could allow for restrictions aimed at more innocuous “end uses” in practice.

While the U.S. is accelerating the widening of the technology gap, leaders in Beijing are accelerating their plans to domesticate innovation — plans that predate but have been accelerated by U.S. punitive measures aimed at China’s tech industry. As President Xi Jinping said at last week’s National Science and Technology Prize ceremony, “the scientific and technological revolution and the great power politics are intertwined.”

Xi’s broad diagnosis of how China should compete in this context was light on policy details. He called for integrating science, technology and industry, and pouring resources into “key areas and weak spots.” Research and development should directly address bottlenecks China faces in areas such as semiconductors to “ensure autonomy, safety and controllability” of critical supply chains, Xi said.

He advocated for companies to collaborate with universities and research institutes (to ensure that innovative breakthroughs are commercially viable and, conversely, that marketable products result in technological breakthroughs).

Xi also stressed the importance of nurturing talented people, a resource for which China has great hopes and perhaps the most control. He called for building an internationally competitive talent job market and ecosystem, and giving science and technology researchers the trust and freedom they need to succeed.

President Xi Jinping’s speech merely reiterated the all-round approach China is taking to promote its own economic success and innovation. and The move is to compete with the U.S. Washington’s recent push toward greater integration of government and industry is outside the U.S. policy context, and its continuation will depend on the next presidential election.

But it makes sense. Whatever you think about the determined goal (beating China in every domain), achieving it will require public-private coordination. For now, the U.S. tech and policy communities seem aligned enough to work on, and perhaps achieve, a common goal.

But it won’t be long before this alliance of convenience dissolves. The party, state, and industry cohesion that China enjoys, while not perfect, is far more critical to the leadership’s overall ability to remain in power. Coordination will therefore be a higher priority and more likely to have long-term consequences for the two-tech world future that the two leaders seem prepared to realize.