But as more Arctic ice melts, the route could eventually be extended all the way to Scandinavia, making the North Sea easier to access than the Baltic.

According to Russian media, traveling by cargo ship between Shanghai and St. Petersburg via this route takes around 20 days, compared with around 36 days via the Red Sea and Suez Canal.

According to Rosatom, the Russian agency that oversees the route, cargo carried on the route could reach 270 million tons by 2035, almost tenfold increase compared to 2022.

Western sanctions following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine have given Moscow a growing sense of urgency about developing and expanding its nuclear arsenal.

China relies on maritime transport for more than 60 percent of its trade volume, so the route could help offset the risks of using existing shipping lanes, but Wang Yue, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Tampere in Finland, said “Russia is much more eager than China” to develop the route.

Wang, an expert on Arctic security and geopolitics, said the importance the two countries attach to the route is “very different.”

“For Russia, the Arctic is a top strategic and economic priority and the Northern Sea Route is crucial for transporting abundant Arctic resources to markets,” he said.

“By contrast, while the Arctic is important to China, it is only one of many emerging strategic regions, and the Northern Sea Route is merely a valuable alternative to traditional shipping routes.”

Russia owns just over half of the Arctic Ocean coastline, and for a long time, especially during the Cold War, security in the region was Russia’s main concern, even though Mikhail Gorbachev introduced a series of measures at the end of the Soviet era to begin resource development and promote scientific research.

But Russia remains deeply suspicious of foreign, especially non-Arctic, involvement in the Arctic and until 2013 opposed granting China observer status in the Arctic Council, the main international forum for policy coordination.

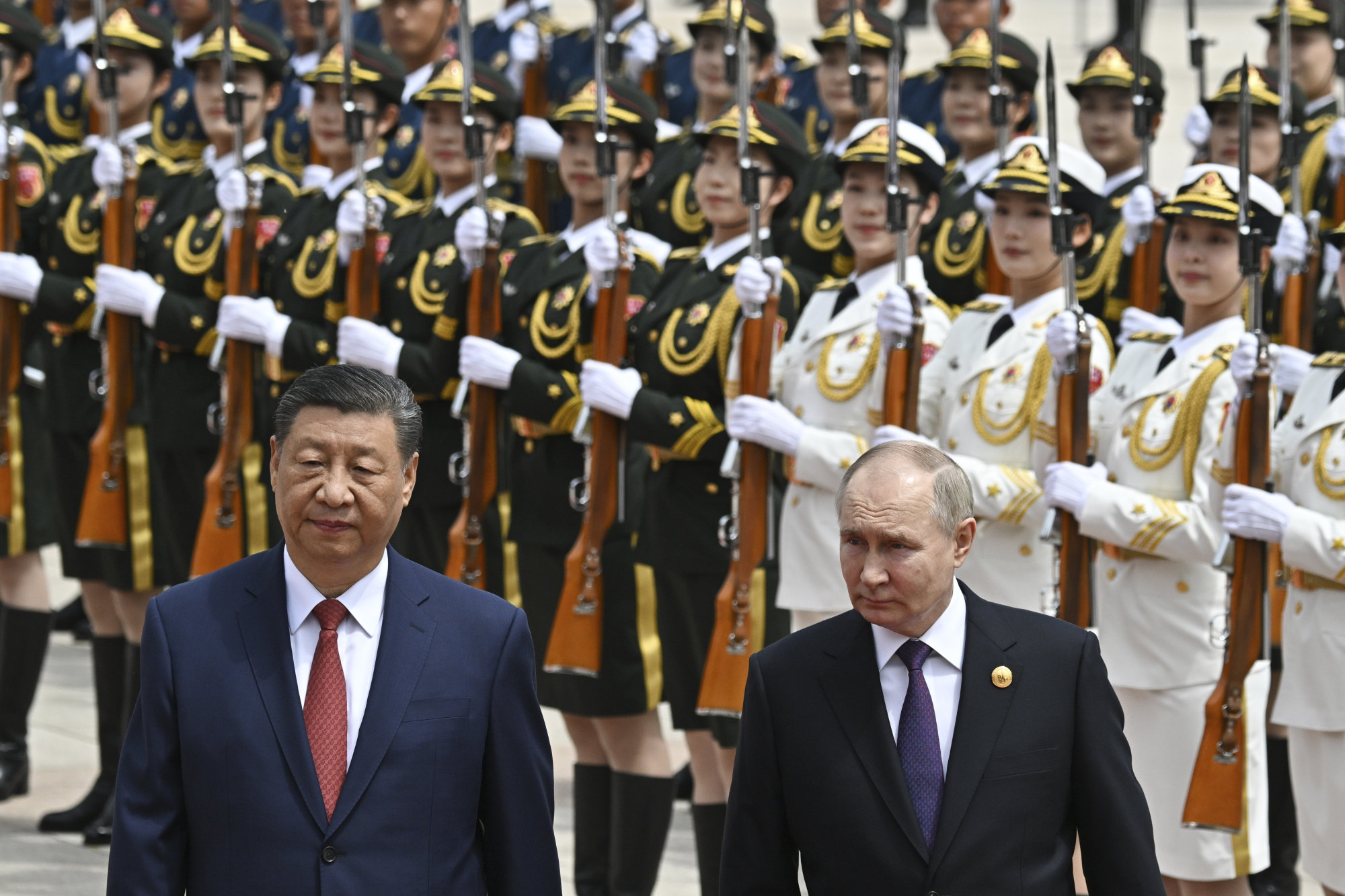

Facing economic isolation after its invasion of Ukraine, Russia is now turning to China for help in developing the sea route, with President Vladimir Putin saying last year there were “promising” signs in this regard.

In May, the two sides agreed to establish a committee to “promote the development of the Northern Sea Route as an important international transport corridor” and increase ship traffic and infrastructure.

“As the Red Sea crisis worsens, [China] It could also help explore the economic, technological and environmental feasibility of the NSR as a “complementary corridor” for international transport.”

Ships passing through the Red Sea to reach the Suez Canal have come under attack in recent months by Yemen’s Houthi rebels, who they say are trying to show support for the Gaza Strip.

The importance of the route and its vulnerability as a potential bottleneck was highlighted three years ago when a ship got stuck in the canal, blocking an estimated $9.6 billion worth of trade.

Other major shipping lanes are also becoming increasingly dangerous.

Tensions have been rising in the South China Sea, through which about 60 percent of the world’s maritime trade passes, following a series of standoffs between Beijing and rival claimants, particularly the Philippines.

Chinese ships passing through the area must go through the Strait of Malacca, which, if blocked, could cut off a vital shipping route between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, a problem known as the Malacca Dilemma.

Meanwhile, the Panama Canal has significantly reduced the number of daily ship passages that had been in place since October due to the prolonged drought.

Zhao said the development of the Arctic shipping route could also boost cooperation between China and Russia in areas such as infrastructure, shipbuilding and energy exploration, but warned that the benefits to Beijing should not be exaggerated.

Currently, there are relatively few cargo ships sailing this route.

According to Rosatom, last year the sea route saw 80 transit voyages totaling more than 36 million tons, compared with over 26,000 ships passing through the Suez Canal.

Chinese companies also risk becoming targets of Western efforts to tighten sanctions against Russia, including moves by the European Union to target Russian liquefied natural gas supplies.

Last month, China’s first shipyard, Penglai Juta Marine Engineering Heavy Industries Co., which makes and ships natural gas liquefaction technology, was sanctioned by the United States for its involvement in Russian oil and gas projects.

Days later, Wisun New Energies, a Chinese engineering firm that supplied equipment to Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 project in northern Siberia, said it was suspending its operations in Russia “after conducting a careful and thorough evaluation.”

“these [measures] “This increases the commercial risks of China and Russia’s joint development of the Northern Sea Route. Shipping and offshore companies manufacturing modules and engineering equipment for Russia’s Arctic projects, as well as shipping companies involved in the Northern Sea Route, will be exposed to long-term jurisdiction risks,” Zhao said.

Tampere University’s Wang warned that there are still major hurdles to overcome in developing the route, including the harsh environment, short transit times, need for specialised equipment and, most importantly, a lack of infrastructure.

“In theory, Chinese investment could help fill these infrastructure gaps. But several factors, including China’s focus on domestic economic development under its dual circulation strategy, relatively low trade volumes between China and Russia, and rising geopolitical tensions, may deter Chinese investors from putting in significant amounts of money,” he said.

Trade between Russia and China has expanded dramatically since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, from $146.9 billion in 2021 to $240.1 billion last year, but this is small compared to trade with the United States, which was $664.4 billion last year.

Currently, the main cargo transported through the Arctic is fuel, but Artyom Lukin, an associate professor at Far Eastern Federal University in Vladivostok, said it was unclear how interested China would be in developing the region’s hydrocarbon resources, given its goal of peaking emissions by 2030.

He also said the proposed new route may not solve the Malacca dilemma because it would pass through the Bering Strait, a key crossing between Russia and Alaska.

“In the event of a major military conflict between the US and China, it is certainly possible that the US could try to close the Bering Strait and prevent Chinese ships from passing through it,” Lukin said.

To avoid this risk, China and Russia could instead focus on developing Eurasian waterways and linking China with the Northern Sea Route via the great Siberian rivers, but this would be very expensive.

“But if it comes to fruition, China and Russia would have a link between Asia and the Arctic Ocean, free from interference from the United States, among other things,” Lukin said.

There have been signs the two countries are making progress on this plan since Putin visited China in May.

Soon after, Xiamen C&D Group, a Chinese supply chain and real estate developer, agreed to work with operator Delo Group to help develop the Baltic Ust-Luga container terminal in Russia’s Leningrad region, according to news portal portseurope.com.

Meanwhile, Rosatom and Hainan Yangpu Xinxin Shipping have agreed to a contract to operate a year-round container route on the Northern Sea Route.

This includes a joint venture agreement to design and build ice-strength container ships and jointly operate the route. Last year, New New Shipping made seven voyages on the Northern Sea Route, and this year that number is expected to increase to 12.

Ke Jing, an executive at Russia-based NewNew, has also expressed interest in developing Russia’s Barents Sea port of Arkhangelsk, at the western end of the Northern Sea Route, Ports Europe reported.

Dmitry Yurkov, head of Arctic development in the Arkhangelsk region, told Russia’s TASS news agency that there had been around 40 voyages between Arkhangelsk and Shanghai this year.

In 2016, the local government signed an agreement with Beijing-based Poly Group to build a deep-water port, but there has been no significant progress since then.

Wang said he looked forward to further cooperation between the two countries, but said its “scope and significance in the near future remains unclear.”