But as the city prepares to welcome dozens of heads of state and government, few are in a party mood; a US president who has called for reviving NATO is in deep trouble; and far-right isolationist politics loom large on both sides of the Atlantic.

NATO is celebrating its 75th anniversary and is still going strong, but it’s hard not to wonder where NATO will be a year from now, and whether it will be around for its 76th anniversary.

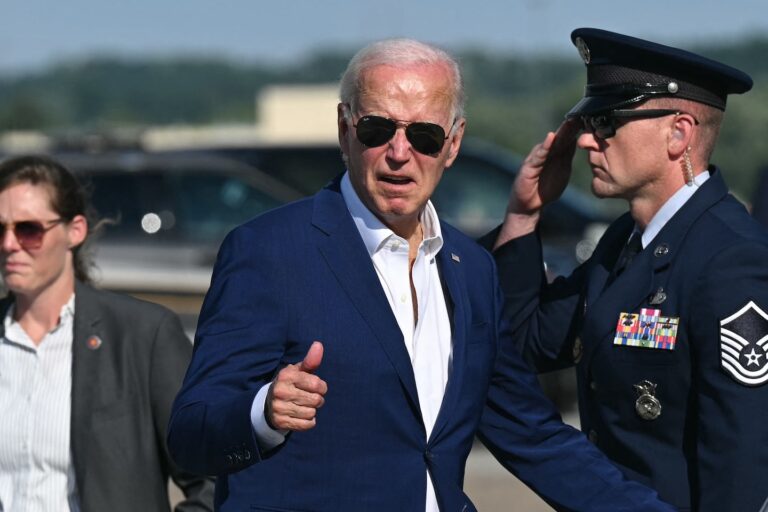

In a three-day meeting that began on Tuesday, President Biden and Western leaders He argues that NATO and the post-World War II order will move forward in a positive direction.

Allies will recall the history that unites them and rally around the need to counter a vengeful Russia, they will explain how they are working to support Ukraine, and they will suggest that NATO is closely watching the budding military alliance between Beijing and Moscow.

Outside the hall of the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, where the official business of the summit takes place. — The storyline is not so optimistic, Biden’s eligibility to become president, President Trump’s chances of re-election, and political turmoil in France.

The summit’s messaging will be tailored to defend the alliance and try to weather the political storm unscathed. The allies will likely emphasize a big increase in defense spending and offer Ukraine more military aid, but the amount will be less than some in NATO circles had hoped for and there will likely be less progress on membership.

This confusion is “All European leaders” said this ahead of the summit, Camille Grand, a former NATO deputy secretary-general and now a distinguished policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Get caught up in

Stories to keep you up to date

“They don’t want to put it on the table out of respect for Biden,” he continued, “but it’s something that everyone is thinking about.”

Focus on US politics

Holding NATO’s anniversary summit in Washington will have symbolic significance, but perhaps not in the way that U.S. officials and diplomats had hoped.

The Biden administration has sought in recent years to rebuild transatlantic relations that were damaged under the Trump administration, renewing relationships with partners and demonstrating strong support for NATO.

“America is back. The transatlantic alliance is back. And we’re not looking back,” Biden declared at the 2021 Munich Security Conference.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a year later seemed to vindicate him, imbuing the alliance with a new sense of purpose, adding Finland and Sweden to the fold, and resulting in more sophisticated plans for deterrence and defense.

But just months before the Washington summit, Trump destabilized the alliance by suggesting he would urge Russia to attack allies if they didn’t spend enough on their defense. At the same time, a months-long delay in U.S. aid to Ukraine highlighted the fragility of U.S. support.

Allies have responded by trying to “counter-Trump” their own programs. NATO will formalize efforts this week to bring some of the activities of the Ukrainian Defence Liaison Group, the U.S.-led Ukraine coordination body that provides a steady supply of weapons to Kiev, under partial NATO control.

The aim is to prevent Trump from cutting off military aid and training to Ukraine. “Going international will make us more able to withstand threats from President Trump,” said a senior NATO official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the alliance’s plans.

Other NATO officials and diplomats say this and other efforts are well-intentioned but simply not enough to stop a determined Trump from undermining the alliance or its support for Ukraine. Congress has approved measures aimed at preventing any U.S. president from unilaterally withdrawing from NATO. But Trump would not need to formally withdraw from the alliance to seriously weaken it; he could do so by repeatedly suggesting he would not defend allies.

Recent questions about whether Biden will be able to remain the Democratic nominee have further deepened European concern, though most leaders are too polite to say so publicly. Behind the scenes, U.S. officials have tried to calm fears by emphasizing that the alliance has weathered all kinds of political turmoil for more than 70 years. “You can’t stop national elections. It’s just part of the DNA of the alliance,” said a senior State Department official, who spoke to reporters on condition of anonymity.

“The alliance has been through everything,” the official said. “This is not something completely unknown.”

European leaders are in a bind

Still, the challenges appear to be mounting. The Washington summit comes amid major political turmoil in France, where President Emmanuel Macron dissolved parliament and called early parliamentary elections for June 30 and July 7 after last month’s European Parliament elections saw huge gains for Marine Le Pen’s far-right party.

Early projections suggest French voters have mobilised to block France’s first far-right government since World War II, but Mr Macron and his centrist movement will likely be constrained.

Macron has long advocated for Europe’s “strategic independence” from the United States and last year sought to lead the European response to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

But the politics of the alliance will be complicated by the uncertainty surrounding Macron’s foreign policy, and French politics in general. “France being at the mercy of the winds is a problem even in peacetime,” columnist Sylvie Kauffmann wrote in the French daily Le Monde last week. “But it will be even more so in a climate where a warring Russia is redoubling its aggression and ostensibly welcoming unrest in Western democracies.”

In Germany, another powerful NATO ally, Chancellor Olaf Scholz is also struggling with economic challenges, a fragile coalition government and the rise of the far right. According to Spiegel, at a party event last week he said he was worried about the situation in France and was exchanging daily text messages with Macron. “We are discussing the situation and it’s really depressing,” he said.

Ukraine’s future at stake

This turmoil is especially bad news for Ukraine, whose immediate survival and long-term prospects depend in part on the fate of the alliance.

At last year’s summit, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky angered allies with furious tweets about not receiving an invitation to join NATO. This year, he will walk away with few gains: a promise of permanent support, a new NATO structure to coordinate aid to Ukraine, military aid for the next year, and a promise of some kind of “bridge” to membership.

With Russian forces advancing into eastern Ukraine and Kharkov under heavy attack, he is unlikely to be satisfied – certainly less than he would expect and less than some would consider necessary to win the war.

Kate Brady in Berlin contributed to this report.