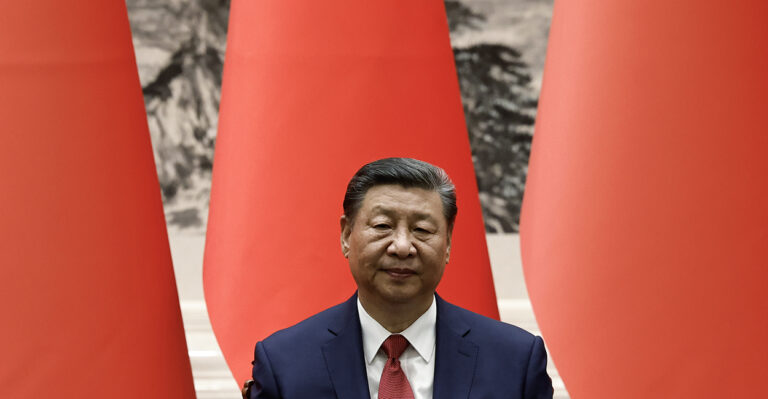

Investors have been volatile in China recently, and President Xi Jinping’s policies have only made things worse. Some are hoping that upcoming meetings of the Chinese Communist Party leadership will improve things, but they are almost certain to be disappointed.

The Communist Party of China’s Central Committee, made up of about 370 senior officials, will hold its third plenary session since taking office in 2022 from Monday to Thursday.

Since 1978, the Third Plenary Session has been associated with economic reform. That year, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping used the session to push through the “Reform and Opening Up” policies that helped transform the then economically struggling country into the powerhouse it is today.

The subsequent third plenary session mostly brought about less dramatic changes, but these meetings are typically focused on long-term economic priorities, making them a natural forum for offering major course corrections. But that seems unlikely to happen.

The upcoming Central Committee Plenum may be momentous, but not for the reasons some might expect: Rather than announcing major policy adjustments aimed at revitalizing the private sector and stimulating a new era of economic growth, the meeting will likely serve to further institutionalize President Xi Jinping’s long-standing agenda.

This was made clear in the official announcement of the event: after finalizing the agenda for the approved plenary session last month, the CPC Central Politburo revealed that one of the key deliverables would be the “Resolution on Comprehensively Deepening Reform and Promoting China’s Modernization.”

For those unfamiliar with party jargon, “deepening reform across the board” has been the name given to President Xi Jinping’s policy agenda for over a decade. It was also the theme of his first Third Plenary Session in 2013.

The result of this plenary session was the formation of a body called the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform, a power grab in itself that gave Xi Jinping much of the policy-making power that had previously been held by China’s premier. (In 2018, this body was strengthened and renamed the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform.)

To most observers, Xi Jinping’s approach to governance is the antithesis of reform: While he has liberalized some areas of the economy, most of the reforms he has implemented over the past decade have fallen far short of the liberal reforms that private businesses want.

But that is not how the Chinese Communist Party measures its success: Xi Jinping’s “reforms” have supposedly made the party stronger than ever, and the party sees its growing influence over business as a good thing.

The Chinese Communist Party not only sees big business as a threat to its monopoly on power, but decades of weakly enforced regulations, combined with Beijing’s total focus on rapid economic growth, have exacerbated risks and imbalances that, if left unresolved, could trigger a crisis and threaten China’s leadership.

Since coming to power, Xi Jinping has sought to reshape the economic model from one focused on quantitative growth to “quality growth” that is slower but better aligned with Beijing’s strategic interests and, in the CCP’s view, more sustainable in the long term. This growth model is characterized by an emphasis on long-term efforts such as technological innovation, high-end manufacturing, supply chain security, and reducing the wealth gap.

This is not just Xi Jinping’s challenge: China’s Communist Party leadership recognized the risks inherent in its growth model long before Xi Jinping came to power, but his concentration of power and ruthlessness have given him unique tools to break down vested interests and institutional obstacles and change the trajectory of the economy.

Many of these efforts will hurt businesses and curb growth in the short term, but party leaders are willing to pay the price in the hopes that they will help China escape the middle-income trap and prevent even bigger problems in the future.

That’s where the upcoming Plenum comes in. Judging by reports so far, a major focus will be on China’s efforts to achieve technological self-reliance and transition to the world’s leading technological power by 2035. This has become especially urgent for the Chinese Communist Party in the face of increasing crackdown measures by the United States and other major suppliers aimed at denying Beijing access to sensitive technologies it deems vital to its economic interests and military modernization.

The meeting is likely to adopt significant measures to advance China’s technology goals, but like other outcomes, these measures will contain few concrete details. What they mean in practice will only become clear as they are implemented over the coming months.

The meeting is also likely to discuss risks related to China’s struggling real estate sector and heavily indebted local governments. Fiscal and tax reforms may be proposed to address these issues. Other possible moves include rural land reform, further easing of China’s household registration system, and breaking down regional protectionism to integrate the country’s various regions into a unified market.

These are all deep-rooted problems that the Chinese Communist Party has no easy way to solve. It would be significant if the decisions announced at the plenary session could resolve some of these problems.

But that’s not the reform businesses want or need.

Of course, the Communist Party cannot ignore the plight of the private sector, and it will likely announce a series of measures aimed at improving the business environment, which hit a 30-year low last year, and attracting more foreign investment.

The Communist Party is concerned about China’s serious economic problems and fears that a worsening situation could lead to social unrest. China also needs to continue to achieve reasonably high growth to reach its goal of becoming a “moderately developed economy” by 2035.

But the CCP does not believe a crisis is imminent: Maintaining growth and appeasing investors is secondary to resolving longer-term structural challenges that could ultimately result in an even deeper crisis for the CCP.

Therefore, attempts to create favorable conditions for Chinese private companies will be limited and will backfire on the “tough love” treatment the party has employed in recent years.

Investors can expect changes and may even be pleasantly surprised at the meeting, but the Chinese Communist Party believes it is on the right path, so a radical course correction seems unlikely.