The space station is, after all, an orbital laboratory, and while there, the astronauts’ job is to conduct science experiments and maintain the station. Now that there are two sets of hands, the work, including the most tedious chores (yes, a little toilet maintenance) is distributed among nine astronauts who live in a spacecraft the length of a football field and with the living space of a Boeing 747.

Williams and Wilmore arrived at the space station on June 6 for a roughly eight-day mission that, as of Friday, had stretched to 51 days. The delay was caused by the sudden shutdown of five of the spacecraft’s thrusters during its approach to the station, followed by a small but persistent helium leak from the propulsion system. Since then, Boeing and NASA engineers have been conducting tests to determine what went wrong and ensure the spacecraft is fit to return Wilmore and Williams safely.

During a briefing on Thursday, NASA officials couldn’t yet say when that might be. They said the Starliner is probably still healthy enough to return with a crew on board, but that decision will be made in a thorough review involving top NASA and Boeing executives, which they said could be scheduled as early as next week.

But they have repeatedly said the astronauts are not being left behind and that in the event of an emergency they can return home on the Starliner. SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft has been ferrying astronauts to NASA’s space station since 2020 and could be used as a backup if needed, NASA officials said.

The mission will be Starliner’s first crewed flight and will test the spacecraft’s capabilities before NASA allows four astronauts to stay aboard the space station for up to six months.

Though the journey to the space station has been eventful, the astronauts said this month they have complete confidence in Starliner and are enjoying their long stays in space while keeping in touch with friends and family back home. Wilmore, 61, is a former Navy captain and fighter pilot from Tennessee. He is married and has two daughters. Williams, 58, is a former Navy captain and helicopter pilot from Massachusetts. He is married and enjoys spending time with the family dog.

“We’ve been very busy here and integrating with the crew,” Williams said at a press conference. “It feels like I’m coming home. It feels good to be floating. It feels good to be in space and working with the team on the International Space Station. So I’m just happy to be here.”

“It’s a great place to live and work,” Wilmore added.

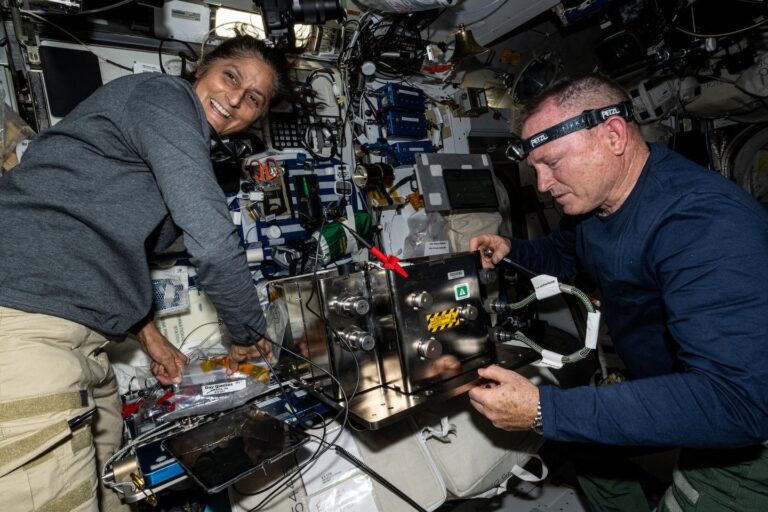

Since arriving at the space station, they have been using ultrasound machines to scan veins and gather data on how space affects the human body. Williams has worked on “using microgravity to produce higher quality optical fiber than we can produce on Earth,” and “using fluid physics, such as surface tension, to overcome weightlessness when feeding and watering plants grown in space.”

In addition to scientific research, there are chores to do, including “some maintenance that’s been on the cards for a while — work that’s been scheduled for a little while,” Williams said.

There, like the crew of a ship at sea, they were tasked with inventorying the base’s food supplies. They replaced a urine-treatment pump. Wilmore, a handyman who builds tables and huts for the church, was tasked with maintaining two freezers that store lab samples and refilling the coolant loop on one of the base’s water pumps.

They’ve also had a bit of a scare. At one point last month, all of the astronauts had to scramble to their spacecraft after a satellite broke apart at high altitude near the space station and posed a potential hazard. Williams and Wilmore hopped aboard Starliner and began preparing to undock in case pieces of the satellite slammed into the station, forcing an evacuation. In the end, the debris passed by without incident, and the crew resumed their work.

Zero gravity is fun, especially once astronauts get used to it and are comfortable flying around the space station. “Gravity is the worst. It’s terrifying,” veteran NASA astronaut Sandy Magnus once said.

But despite the wonder of orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour, experiencing sunrises every 90 minutes, and seeing entire continents within sight, space can get tiring. Even the toughest astronauts get homesick. The space station can feel cramped. Going to the bathroom is a delicate procedure that involves suction and is uncomfortable. And the lack of gravity means astronauts have constant stuffy noses as fluids shift around their bodies.

“I think the ideal space mission would probably be about a month, so you have enough time to start getting back to normal and then you can go home,” Scott Kelly, a former NASA astronaut who spent nearly a year aboard the space station, said in an interview.

With extra people on the space station, food supplies would run out more quickly and systems designed to remove carbon dioxide from the space station’s air would have to be run more frequently. “It would put a little strain on that,” Kelly said. “On the other hand, four extra people would do more work. And there always seems to be a lot of work to do in space, so that’s a plus.”

Astronauts train for every scenario, especially if things go wrong, he said, and ground crews work tirelessly behind the scenes to keep the astronauts safe.

“They hold our lives in their hands and are very professional,” Kelly said. “Space flight is dangerous and there are risks. Things can go wrong. But you have to trust the hardware and the people, and I’m confident they’ll be OK.”

Extending astronauts’ stays on the space station is something NASA has done before: In 2022, a major leak occurred on the Russian spacecraft carrying NASA astronaut Frank Rubio and two Russian cosmonauts to the space station, forcing Russia to send a rescue ship to bring them home. That doubled Rubio’s planned six-month stay, making him the longest-ever American in space at 371 days.

The extension was difficult at first, he says. “It was tough because I knew it would mean being away from my family for longer than I expected,” he told NPR. “But I also knew they were making the right decision in terms of our safety. … And once I got over the initial shock and surprise, I was focused on doing the best I could and making sure we accomplished the mission.”

He says spending so much time in space has really helped him adapt and adjust well to living and working in a weightless environment. “I was incredibly lucky to be able to put the lessons I learned into practice right away. A lot of people have to wait five, six, 10 years,” he told Space.com. [for a second mission] Until I can put what I’ve learned into practice.”

Before their Starliner flight, Wilmore and Williams had been looking forward to returning to space for years — each had been on two previous space flights, spending more than 500 days in space combined, and were eager to get back on the ground.

In a pre-flight interview, Williams said she recognized that because this was a test flight, she and Wilmore might have to improvise. “We expect everything to go according to plan,” she said. “But if it doesn’t, we can just take a little bit of time to analyze it, talk about it, and we’ll be OK. So we have a high level of confidence in this mission.”

She added: “I’m not unhappy with us staying here for an extra two weeks.”