PUBLISHED

December 28, 2025

A new report by the UN Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team lends international credence to a claim Pakistan has made for years: Afghanistan has once again become a staging ground for militant groups and a haven for terrorists. More damning still, the findings cut directly against the Taliban’s repeated denials, reinforcing Islamabad’s argument that the region’s security challenges cannot be wished away by rhetoric alone.

The UN document — released early this month — confirms the Taliban’s growing control over major Afghan cities but warns that the regime’s governance and security model remains insufficient for effective policing, rule of law, and counterterrorism, particularly in rural and border areas. “Structural weaknesses, corruption, limited accountability, and internal factionalism further erode their capacity to ensure lasting security,” states the report.

In the 2021 Doha Agreement, the Taliban committed to preventing Afghan soil from being used for militant operations against any country. However, they appear to have reneged on their pledge as the UN report says, “Afghanistan continues to host more than 20 international and regional terrorist organisations, some of which use Afghan territory to plan, facilitate or launch external attacks.”

The regime in Kabul insists that no terrorist groups operate in or from Afghanistan. That position, however, collapses under the weight of evidence presented by UN member states. As the UN monitoring committee puts it, the Taliban’s handling of terrorism remains the central concern. “The de facto authorities continue to deny that any terrorist groups have a footprint in or operate from its territory. That claim is not credible,” adds its report.

The terror ecosystem

Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K) emerges as the most potent threat emanating from Afghanistan — both domestically and internationally. “Although Taliban counterterrorism operations in 2025 have degraded the group’s leadership and reduced the number of attacks inside Afghanistan, IS-K remains resilient and operational,” says the UN committee.

The group operates in small, covert cells in northern and eastern Afghanistan, retaining the capability to target foreign interests. The report says that IS-K increasingly uses AI, cryptocurrencies, and encrypted platforms for propaganda, recruitment, funding, and operations. The UN estimates the group’s strength at around 2,000 fighters, with leadership mostly Afghan and the rank-and-file increasingly Central Asian.

The UN committee tears into the claims of Taliban chief spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid, who alleged in September this year that IS-K leaders and members had been relocated to Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa — provinces he claimed were being used as training and indoctrination hubs for the group.

Much to Mujahid’s embarrassment, however, the UN report acknowledges that Pakistan’s actions have degraded IS-K’s operational and media capabilities, particularly citing the arrest of IS-K top propagandist Sultan Aziz Azzam in May 2025 as a “significant development.”

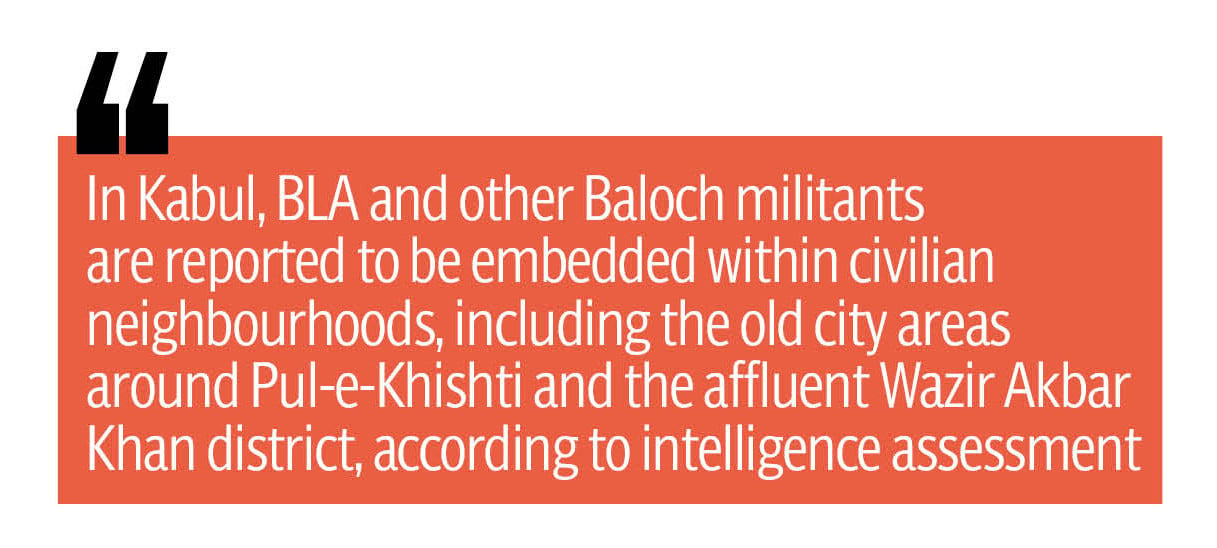

The committee also reinforces Pakistan’s concerns about the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the umbrella group behind much of the country’s violence. It identifies TTP as the most immediate and destabilising regional threat, particularly for Pakistan. “The TTP operates from Afghan territory and has carried out numerous high-profile attacks inside Pakistan during the reporting period,” states the report.

The TTP has intensified attacks on Pakistan’s military, state institutions, and economic targets, including military-owned businesses and Chinese-linked projects, with over 600 incidents in 2025, many involving complex, coordinated operations. Attacks prompted cross-border strikes, casualties, and border closures, straining Afghanistan-Pakistan relations.

“The Taliban continue to harbour TTP leadership, provide logistical space and financial support, despite internal disagreements over the group,” reads the report. The UN assesses TTP’s strength at around 6,000 fighters, based mainly in eastern Afghan provinces, and notes that Taliban leaders are unlikely to act decisively against TTP due to ideological, historical, and personal ties.

Apart from IS-K and TTP, the UN monitoring team also flags the ongoing presence of several other militant groups, including the Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement/Turkistan Islamic Party (ETIM/TIP), which has expanded into Badakhshan and the Wakhan corridor, and promotes attacks against Chinese interests; Jamaat Ansarullah, which seeks to destabilise Tajikistan and Central Asia; Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU); Khatiba Imam al-Bukhari; emerging groups such as Ittihad-ul-Mujahideen Pakistan, considered a front for TTP; and al Qaeda operations.

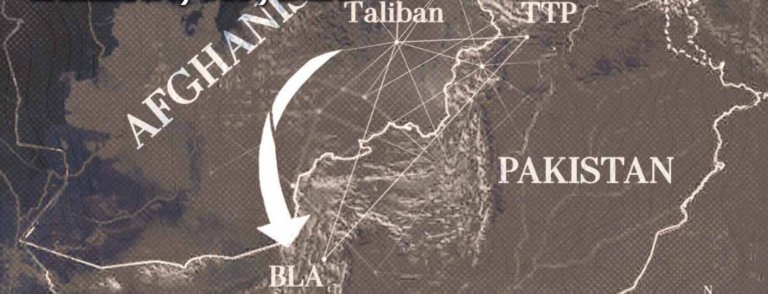

These groups operate mainly in eastern and southern parts of Afghanistan, though they maintain a presence in almost the entire country. In the southern provinces of Kandahar, Helmand, Zabul and Uruzgan, the TTP, Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and al Qaeda have shared training camps. Afghanistan’s eastern provinces, particularly Kunar and Nangarhar, continue to function as havens for militants of various affiliations. Ghazni and Khost have emerged as key training and relocation zones for TTP fighters. Kabul, meanwhile, is the strategic coordination hub, particularly for ETIM/TIP engagement with Taliban regime officials.

These groups operate mainly in eastern and southern parts of Afghanistan, though they maintain a presence in almost the entire country. In the southern provinces of Kandahar, Helmand, Zabul and Uruzgan, the TTP, Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and al Qaeda have shared training camps. Afghanistan’s eastern provinces, particularly Kunar and Nangarhar, continue to function as havens for militants of various affiliations. Ghazni and Khost have emerged as key training and relocation zones for TTP fighters. Kabul, meanwhile, is the strategic coordination hub, particularly for ETIM/TIP engagement with Taliban regime officials.

“Many of these groups maintain working relationships with the Taliban, avoid confrontation with the de facto authorities, and exploit Afghan territory for training, recruitment and financing,” says the UN report. “The continued presence of these groups poses a direct threat to neighbouring states, exacerbates regional instability, and undermines international confidence in Taliban counterterrorism commitments.”

In a latest development, militant groups held a highly secretive meeting in Aybak, the capital of Afghanistan’s Samangan province, on November 4-5, 2025. Representatives from TTP-Jamaatul Ahrar, East Turkestan Liberation Front (ETLF, a faction of ETIM), Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), Taliban Movement of Tajikistan (TTT), BLA, and Iran-based Sunni militant group Jaish al-Adl attended the meeting.

No official representatives of the Taliban regime attended the meeting. Sources said logistical support was provided by Mullah Karamat Ullah, son of Balkh Governor Mullah Yousaf Wafa. While the outcome remains unclear, the meeting was reportedly aimed at improving coordination among the groups. Key attendees included Hassan (Mohsin) Qadir (TTP-JuA), Hamza Uzbek and Yahya Uighur (ETLF/ETIM), Abdul Rahman Badakhshani (TTT), Haml Munshi (BLA), Maulvi Salman Farsi alias Farooq Shadida, (Jaish al-Adl), and Abdul Razzaq al-Marzooq Muhammad (IMU).

The Taliban’s continued deniability has tested Pakistan’s patience amid a surge in terrorist attacks, prompting punitive strikes against TTP sanctuaries inside Afghanistan earlier this year. The reprisals ignited deadly border skirmishes between the two neighbours, accompanied by a sharp escalation in rhetoric as diplomatic ties sank to their lowest point.

Taliban interim foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, for his part, argued that preventing TTP crossings was Pakistan’s responsibility, citing its military and border security apparatus. He dismissed Islamabad’s demand for guarantees that the TTP would not use Afghan territory to launch attacks as “unrealistic”, instead accusing Pakistan of repeatedly violating Afghan territory through drone strikes.

The deadly nexus

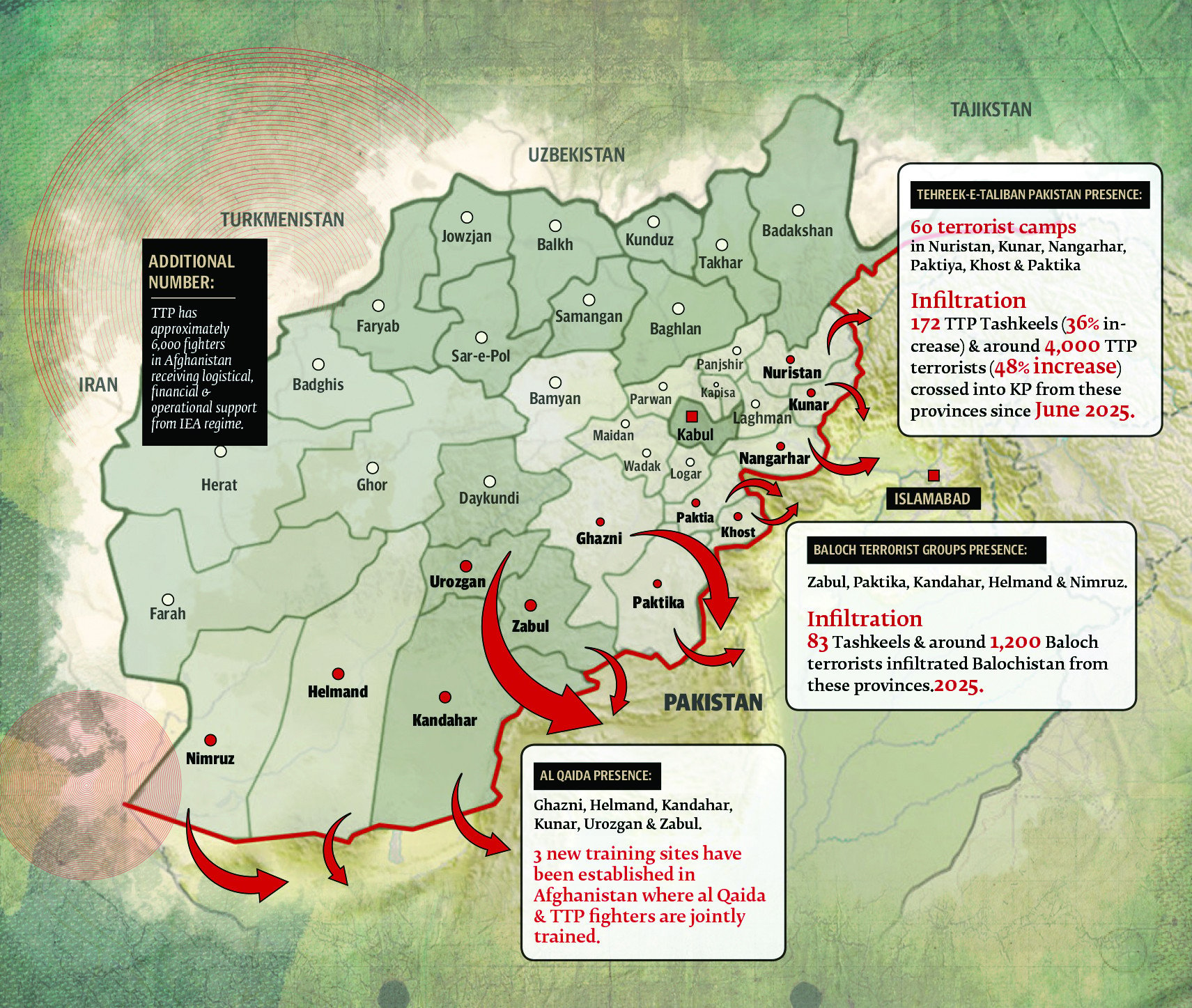

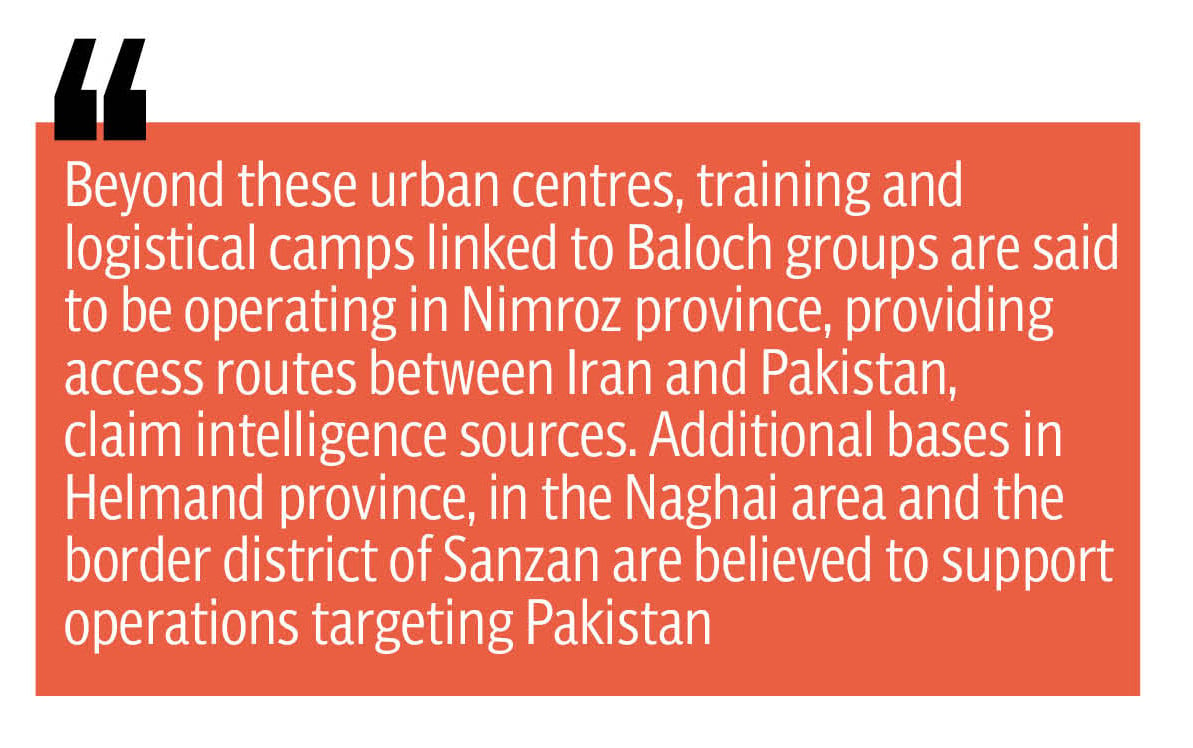

Intelligence assessments point to a sustained presence of Baloch militant groups, including BLA, in Afghanistan. Senior figures are believed to be operating from Kandahar and Kabul, with Kandahar’s Ain-o-Mina area long identified as a logistical hub. A senior BLA operative, Aslam Achhu, was killed there. In Kabul, militants are reported to be embedded within civilian neighbourhoods, including the old city areas around Pul-e-Khishti and the affluent Wazir Akbar Khan district.

Beyond these urban centres, training and logistical camps linked to Baloch groups are said to be operating in Nimroz province, providing access routes between Iran and Pakistan, claim intelligence sources. Additional bases in Helmand province, in the Naghai area and the border district of Sanzan are believed to support operations targeting Pakistan.

While the most recent UN monitoring report does not address the issue directly, the UN Security Council’s Sanctions Monitoring Committee reported in July that member states had confirmed close coordination between the BLA, including its elite suicide unit, the Majeed Brigade and the TTP in parts of southern Afghanistan. The groups are known to receive ideological and weapons instruction from al-Qaeda-linked facilitators at shared bases.

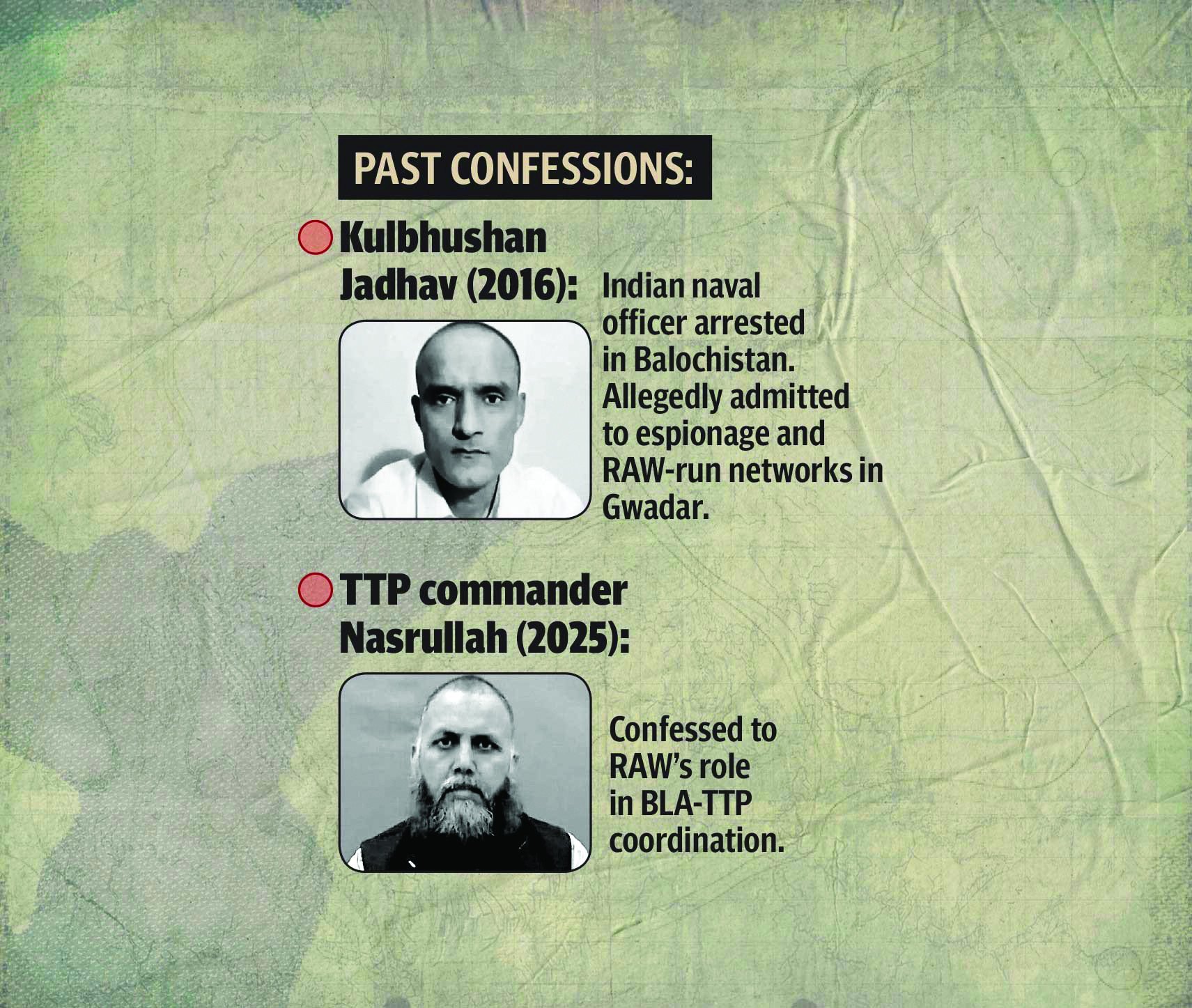

Confessions from arrested senior militants reinforce these findings. Nasrullah, also known as Maulvi Mansoor, head of the TTP’s Defence Shura, told investigators that senior leaders, including TTP’s Noor Wali Mehsud and BLA’s Bashir Zeb, had met repeatedly in Kabul to align strategies, with a particular focus on Pakistani security forces and CPEC projects.

Analysts argue that public evidence of a unified command-and-control structure remains limited. However, several recent BLA terror attacks — including the high-profile Jaffar Express train hijacking in March that killed nearly three dozen people — have demonstrated a level of sophistication suggestive of shared planning or support.

A 2023 policy brief by the Indian Council of World Affairs noted that TTP has sought to broaden its appeal in Balochistan by amplifying long-standing grievances, including enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and the exploitation of local resources. When the BLA carried out attacks in Nushki and Panjgur in February, the TTP publicly welcomed them, with its spokesman declaring that the groups shared a common enemy.

Since mid-2022, at least four Baloch factions have aligned with TTP for logistical support and influence, according to the brief. The TTP has since established two operational chapters in Balochistan, one covering Baloch-majority areas along the Makran coast and another in Pashtun-dominated districts bordering Afghanistan. Both lie along critical sections of CPEC’s western route, including Gwadar, a centrepiece of the project.

Given the situation, China has repeatedly raised concerns about security risks in Pakistan, and political and economic pressures have already slowed progress on CPEC. Security assessments indicate that the deepening alignment between the TTP and Baloch groups has further undermined the investment climate.

India’s visible footprint

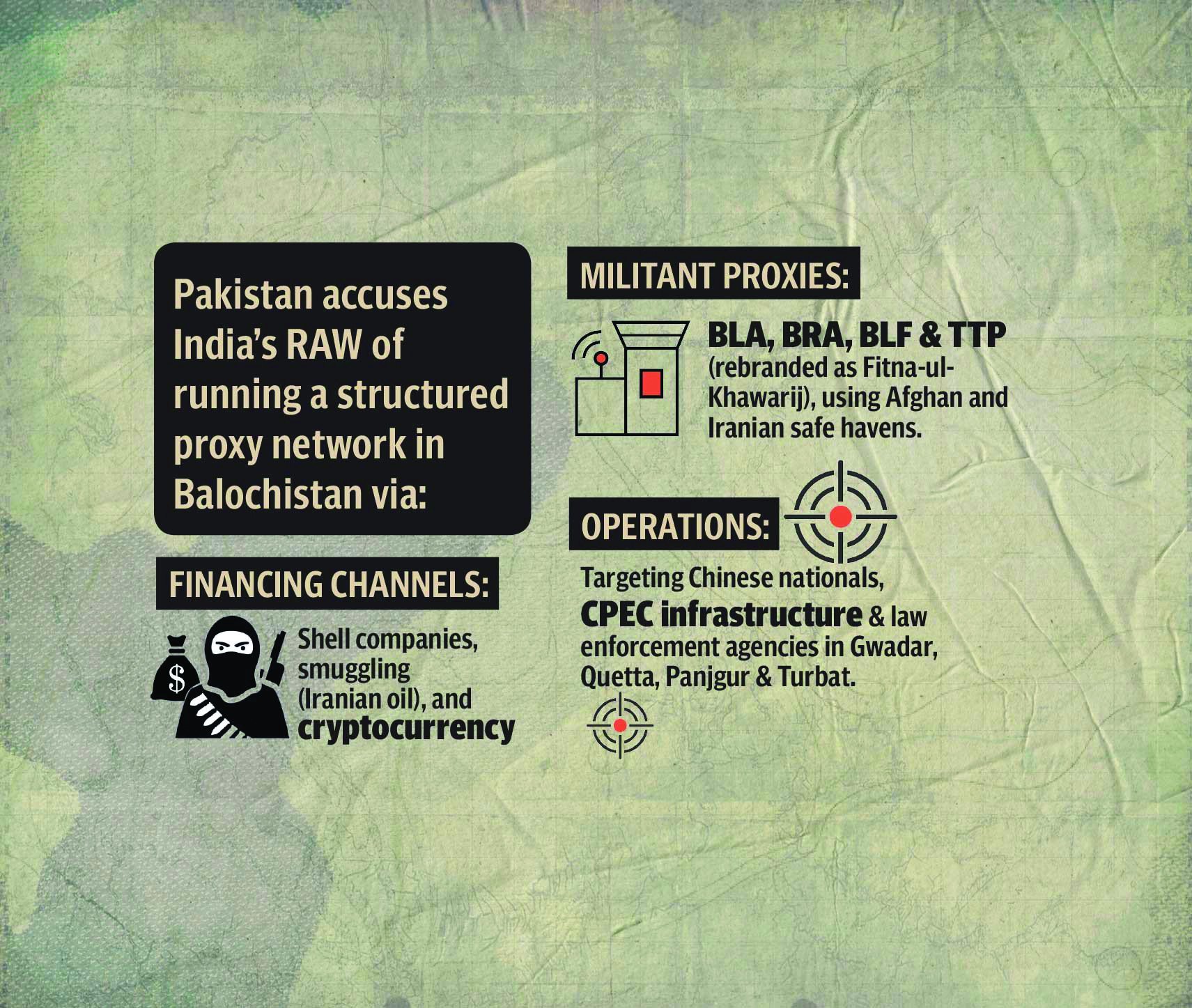

Islamabad has long accused India, its intelligence agency RAW in particular, of using Afghan territory to support terrorist groups, notably TTP and Baloch outfits, as part of what Pakistan calls the ‘Doval Doctrine’, aimed at destabilising the country through hybrid warfare. Pakistan is so convinced of Delhi’s involvement in unrest in Balochistan that it has officially designated the BLA and other Baloch groups as “Fitna al-Hindustan.”

In 2018, various Baloch groups joined hands to form the Baloch Raji Ajoi Sangar (BRAS), or Baloch National Freedom Movement, to mount a coordinated campaign against the state. According to sources, in a recent development, senior Taliban military officials, Logar province commander Qari Karimullah and brigade commander Haji Din Dost met in Kandahar in March 2025 with BRAS leaders Bashir Zeb, Gulzar Bugti, and Rehan Kurd, alongside an Indian delegation.

The meeting followed an earlier BRAS gathering in Iran, where Indian operatives reportedly proposed launching a two-front proxy campaign against Pakistan and Iran. “Initially, BRAS chief Bashir Zeb and BLF leader Allah Nazar were reluctant, fearing Iranian retaliation that could cripple their networks,” a source confirms. “The deadlock eased after the Taliban representatives assured them of protection and logistical support, arguing that the Taliban’s strained relations with both Islamabad and Tehran created room for cooperation.”

During the Kandahar meeting, according to sources, India pledged full backing to the Taliban against Pakistan, including financial support for TTP, and urged Kabul’s rulers to allow BRAS to resume operations from Afghan soil. In return, India is said to have offered fresh investment commitments in Afghanistan.

BRAS reportedly sought control of its former camp in Kandahar’s Ain-o-Mina area, while India proposed financing a new Taliban military facility in Takhta Pul district, in exchange for stationing BLA fighters there. After consulting his father, former Kandahar governor Haji Yousaf Wafa, Taliban official Qari Karimullah gave conditional approval, subject to the consent of Taliban supreme leader Mullah Haibatullah Akhunzada, sources said.]

Free flow of weapons

The question remains as to who is financing this terror industry. Intelligence assessments point to a mix of diaspora donations routed through informal transfer systems, extortion, smuggling, and kidnappings for ransom. India, meanwhile, is also viewed as contributing to these funding channels. The Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, providing a permissive environment, has heightened fears of strategic-level coordination between Kabul and New Delhi.

Since the fall of Kabul in August 2021, TTP and BLA have carried out increasingly deadly attacks. Pakistani officials argue that the groups gained access to modern weapons left behind by US forces, while porous borders and shared training camps allowed them to familiarise themselves with sophisticated arms and receive tactical instruction.

The US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) has exposed the scale of the misstep. In its report released earlier this month, SIGAR notes that the US spent over $148 billion attempting to build a stable, free Afghanistan, with roughly 60% allocated to security initiatives. That included procurement of 96,000 ground vehicles, 51,180 tactical vehicles, 23,825 Humvees, nearly 900 armoured combat vehicles, 427,300 weapons, 17,400 night-vision devices, and at least 162 aircraft.

“When the United States evacuated in August 2021, it left behind roughly $7.1 billion in equipment it had provided to the ANDSF (Afghan defence forces),” the report states. “All of it fell into the hands of the Taliban. These US taxpayer-funded weapons, equipment, and facilities now form the core of the Taliban’s security apparatus.”

The intricate struggle

According to an official tally, the Pakistani military has conducted more than 78,000 intelligence-based operations (IBOs) across Balochistan this year alone. These operations have led to the arrest or elimination of 707 terrorists. But the human cost remains high: 202 security personnel and 280 civilians have been killed in attacks across the restive province. Officials say IBOs are not large-scale campaigns; they are precise, intelligence-led actions designed to dismantle networks while minimising collateral damage. Rights activists, particularly the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), allege abuses, including enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

Government officials, in turn, argue that BYC seeks legitimacy for BLA, a US-designated global terrorist organisation. They say Aslam Achhu, founder of Majeed Brigade, was closely linked with Abdul Ghaffar Langove, father of BYC chief Dr Mahrang Baloch. Both were supporters of BLA founder Khair Bakhsh Marri and his son Balach Marri. Officials claim Achhu drew Langove into active militancy.

Gulzar Imam, alias Shambay, founder of the Baloch Nationalist Army (BNA), who surrendered in 2023, described Langove as a “grassroots organiser” of the Baloch insurgency, contradicting narratives of state involvement. Officials say that the Langove family later received state support — including a scholarship and government employment for Mahrang — yet the BYC chief continues to support secessionist groups and refuses to condemn rights abuses.

Balochistan’s vast mineral wealth — gold, copper, coal and rare earth deposits — gives the province enormous economic potential. Western nations are also showing growing interest, while China is developing the Gwadar port as part of its multibillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative. But the province’s promise remains unrealised while violence and instability persist.

Analysts warn that the convergence of so-called jihadi groups, such as TTP, with ethno-nationalist outfits like BLA combined with continued Indian support has expanded the operational theatre for Pakistan’s security forces, enabled more sophisticated attacks, and allowed militants to exploit cross-border sanctuaries. High-profile attacks and fragile diplomatic relations with the Taliban add pressure on authorities.

Analysts say the complexity of the threat in Balochistan calls for a multi-pronged response combining security, political, and diplomatic measures. They argue that targeted operations are needed to disrupt militant alliances, especially TTP-BLA nexus, while longer-term stability depends on addressing local grievances through political inclusion, economic development, and improved governance. At the diplomatic level, analysts advocate a dual-track effort to press the Taliban regime to give up support for transnational groups and to draw international attention to India’s use of militant proxies.