PUBLISHED

January 25, 2026

KARACHI:

The Taliban regime is not collapsing — yet. But the strain is unmistakable. What once appeared to be a unified movement is increasingly revealing deep internal divisions that the leadership can no longer hide. In truth, the Taliban were never a monolith. They were a coalition of disparate fighters, tribesmen, clerics, and madrassah students bound together by a common objective: driving US-led forces out of Afghanistan.

That objective was achieved in August 2021. What followed was not unity, but a slow, grinding struggle over control of the post-war order. At the heart of this struggle lies a widening rift between the Kandahari clerical establishment, guardians of the movement’s ideological core, and the Haqqani Network, the insurgency’s most formidable military arm. For two decades, the Haqqanis carried the burden of the battlefield, while the Kandaharis provided religious legitimacy. Since the Taliban’s return to power, however, that fragile balance has steadily eroded.

Those tensions have now boiled over, spilling into the open. A leaked audio recording of the Taliban’s reclusive supreme leader, Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada, laid bare the schisms. In the audio, he warned that internal infighting could bring down the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” (IEA), a name they use for their regime. Interestingly, the speech was delivered a year ago at a madrassah in Kandahar, the ideological mecca of the Taliban. The chasm has only widened since, encouraging centrifugal forces to challenge Kabul’s writ. Dormant ethnic groups have dusted off their weapons, seeking to exploit the Taliban’s infighting.

Kandaharis vs Haqqanis

Differences surfaced three days after the Taliban’s victorious march into Kabul. The movement’s Supreme and Administrative Shuras convened to decide who will get what in the new political set-up. The Kandaharis wanted to deny the Haqqanis key positions.

According to sources, Sirajuddin, who was second only to Hibatullah, saw himself as the rightful choice for the prime minister’s post. However, the Kandaharis, particularly their key leaders Mullah Amir Muttaqi, Mullah Abdul Salam Hanafi, Mullah Muhammad Ali Hanafi, Gul Agha Ishaqzai, and Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar shot down the proposal.

Sirajuddin’s Haqqani Network played a crucial role in the insurgency against American forces. But the Kandahari leaders argued that victory was won not on the battlefield but at the negotiating table, where the Taliban negotiators were predominantly from Kandahar. They insisted, therefore, that the prime minister should come from Kandahar. At one point, the disagreement reportedly escalated into a scuffle between Sirajuddin’s late uncle, Khalil Haqqani, and Mullah Baradar.

But the Kandaharis had the last laugh — thanks to their dominance in the Shuras and Hibatullah’s tacit support. A power-sharing formula was agreed upon under which Kandahari deputies were assigned to all powerful Haqqani ministries. Sirajuddin’s Ministry of Interior, for example, was effectively overseen by Mullah Ibrahim, a Kandahari, who controlled intelligence, which also led to TTP-related issues and border skirmishes with Pakistan.

Haqqanis on the back foot

The conflict didn’t end there. The Kandaharis continued to marginalise the Haqqanis, using a reconciliation commission and controversial actions such as demolishing a madrassah of Sirajuddin’s father Jalauddin Haqqani in 2024. In January 2025, a disillusioned and disgruntled Sirajuddin flew to Dubai, sparking rumours that he had resigned. He was convinced to return in March, but tensions didn’t abate.

As late as October last year, the situation escalated further. Sirajuddin and Hibatullah met in Kandahar to resolve their differences. The former set five conditions for reconciliation: restore the Haqqanis’ share in power; honour agreements; lift girls’ education ban; fulfill international commitments; and implement the general amnesty announced for ‘mujahideen’ who had fought against the Soviet Union, according to sources.

Hibatullah, however, mocked Sirajuddin as an “agent of Pakistan and the United States.” Sources reveal that the meeting ended in bitter exchanges and threats between Sirajuddin and Balkh province Governor Mullah Yusuf Wafa, dashing hopes for reconciliation.

Some analysts downplay these differences. “After Taliban founder Mullah Omar’s declared death over a decade ago, some senior commanders revolted against the then newly appointed supreme leader, Mullah Akhtar Mansoor,” says senior journalist Haq Nawaz, who covers militancy and Afghanistan for international media. “The matter was eventually resolved amicably.”

Agreeing with Haq’s assessment, Imtiaz Gul, Executive Director of Center for Research and Security Studies, points out: “Serious disagreements within the Taliban ranks exist but they should not be misconstrued as serious rifts.”

“The fact that Kandahar placed people of its choice in Haqqani-run ministries itself manifests Kandahar as the GHQ of the movement,” he adds. “Everyone realises that they draw strength from unity under the political mecca and only the supreme leader counts at the moment.”

Hardliners vs pragmatists

The current differences are largely political and administrative, but ideological rigidity and tribal rivalries have only made them worse. “The Haqqanis belong to the Pashtun Zadran tribe, while the Kandaharis come from the Mohammadzai lineage, so there are clear tribal differences,” says security analyst Maj Gen (retd) Inamul Haque. “There is also a divergence in worldview: the Haqqanis are more pragmatic, whereas the Kandaharis are hardliners with a puritanical outlook.”

The Haqqani Network, once considered the deadliest Taliban faction, has always maintained a distinct identity within the movement. Even during the final push to Kabul in 2021, while other groups were absorbed, the Taliban formed a treaty-based alliance with the Haqqanis.

The Kandaharis have since strengthened their control over Kabul as well as the provinces. “The Kandahari group, led by the Amir and his close hardline allies, continues to push radical policies such as a ban on girls’ education, media restrictions, and controls on the internet, etc. The Haqqanis, supported by moderate leaders, have been resisting these steps calling for pragmatic policies compatible with international and regional situations,” explains Mansoor Ahmad Khan, Pakistan’s former ambassador in Kabul.

Analyst Ihsanullah Tipu Mehsud agrees, saying that the split between the “spiritual order and the political leadership” is nothing new for Afghanistan-watchers. Reports of disagreement between Kandahar and Kabul have consistently emerged for a couple of years now. However, this time the disagreements seem to be worryingly deep.

Moderates pushed out

The Taliban ban on female education has effectively prevented more than 2.2 million girls from attending secondary school and barred women from universities. The hardline policy has not only ratcheted up international pressure on Kabul but has also triggered divisions within the movement.

According to Mehsud, who identifies girls’ education, internet restrictions, and the supreme leader’s authoritarianism as main points of contention, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai — a Sirajuddin ally and moderate Taliban figure who played a central role in the Doha negotiations — publicly opposed the ban on female education, and was subsequently sidelined.

“The supreme leader’s interference extends beyond appointing ministers or deputy ministers; it trickles down to the district level, affecting the selection of political staff and lower-ranking officials too,” says Mehsud, who specialises in the Taliban, regional jihadist groups, and security issues. “The interior and defence ministries, led by Sirajuddin Haqqani and Mullah Yaqoob respectively, are particularly unhappy with this intrusion.”

Within the Taliban theocratic order, the Amirul Momineen is assisted by three deputy Amirs: Sirajuddin Haqqani, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, and Mullah Yaqoob. Unlike regular cabinet ministers, the trio considers itself entitled to consultation on key decisions, reflecting its higher standing within the movement.

Family ties & tribal fault lines

The Taliban are riven not only by political and administrative conflicts, but also by struggles over resources and ethnic favouritism — fractures that threaten to destabilise the movement from within.

Under Mullah Omar, the movement was characterised by austere simplicity and integrity, but the current regime is increasingly dogged by allegations of nepotism, self-interest, and tribalism. Competition for control of natural resources, minerals, and trade routes, particularly gold mines in Badakhshan and coal deposits in the north, has sparked deadly clashes between Kandahar-aligned leaders and local Taliban factions.

Ethnic divisions have further exacerbated tensions. The Taliban remain Pashtun-centric, and under Hibatullah, non-Pashtun members, especially Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras in the north, are kept out of key offices. Appointments of Pashtun officials, such as Mullah Yusuf Wafa in Balkh, have fueled resentment, while important figures like Qari Fasihuddin Fitrat, the Afghan military’s Tajik chief, are forced to rely on the Kandahar secretariat due to their non-Pashtun background. These dynamics point to both factional vulnerabilities and governance challenges within the regime.

Fragmentation within the Taliban’s second- and third-tier leadership is reportedly stoked by alleged corruption and the dominance of a handful of powerful families. A coterie of influential figures and their relatives is said to have the final say over major foreign investments in mines and mineral sectors — something even the Kandaharis have resented.

Senior Taliban leaders, including Sirajuddin, have publicly admitted that nepotism is undermining governance. Currently, four families are widely believed to dominate key state institutions, concentrating power and wealth while sidelining veteran fighters. Prominent among them are the families of Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, Deputy Petroleum Minister Shahabuddin Delawar, Balkh Governor Mullah Yusuf Wafa, and Taliban founder Mullah Omar.

Based in Dubai, Mullah Muttaqi’s brother, Ahmed Nabi Muttaqi, allegedly bags kickbacks or partnerships in official business deals. Four other brothers — Muhammad Nabi, Ahmadullah, Abdullah Muttaqi, and Amanullah — also hold top government positions.

Delawar’s family, too, is embedded in the government. His son, Maghfoorullah Shahab, serves as Afghanistan’s ambassador to Uzbekistan; his son-in-law, Shamsuddin, works at the Kabul Development Agency; another son, Roohullah Shahab, is an adviser in the Ministry of Economy; and a nephew, Moeedullah Ehsas, holds a position in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Mullah Wafa sits atop a massive stockpile of sophisticated weapons which he seized from depots in Spin Boldak, Kandahar, and surrounding areas during the US exit from Afghanistan. His son and two brothers also hold influential positions in the regime. During his lifetime, Mullah Omar did not allow any family member to hold any office within the movement. Today, however, his son Mullah Yaqoob, his brother Mullah Manan Omari, and several other relatives occupy senior positions in the regime.

Threatening the emirate

Analysts believe the widening divide between the Kandaharis and the Haqqanis, coupled with allegations of nepotism, favouritism, corruption, and power and resource grabs, is deepening internal divisions within the Taliban and threatening the very foundation of the power structure.

“When internal disputes move beyond ideology to competition over illicit drug trade, taxation, and lucrative smuggling routes, factions may fight to secure financial backing, as witnessed in reports of skirmishes between the Haqqani and Kandahari factions,” says Kabul-based security analyst Hidayat Ullah Tani.

But Ambassador Mansoor doesn’t see any threat to the regime, at least in the near future. “I doubt at the moment they [differences] pose a significant challenge to the Taliban rule. That is why many other countries are gradually increasing engagement with the Taliban government. Thus, a change seems unlikely during the next couple of years,” he adds.

Inam, however, believes that the regime’s unraveling is only a matter of time if these divisions are not healed. “What is happening in Iran, where Western powers are attempting a regime change, could be attempted in Afghanistan as well,” he adds.

The supreme leader’s tight grip

Some analysts believe the regime’s greatest threat could stem from the supreme leader’s authoritarianism, as he literally micromanages government affairs. In October 2025, Hibatullah ordered an internet blackout, but Kabul restored the service. Furious, he summoned Kabul Governor Mullah Aman Noorzai and demanded an explanation from Sirajuddin and two others for “defying” his order.

“Kabul appears to be largely irrelevant in political decision-making. The interim prime minister, Mullah Hassan Akhund, reportedly at one point stopped attending his office, complaining that he was merely a ‘rubber stamp’,” notes Nawaz. “The Taliban political structure is weak, as all final decisions continue to come from Kandahar,” he adds.

In the long term, Gul says, Hibatullah’s highly centralised decision-making and religio-cultural intransigence will neither inspire trust among the majority nor insulate it against external pressures with internal implications.

Nevertheless, the supreme leader is unlikely to loosen his grip on power. “He will respond more aggressively to dissent because he knows he holds spiritual authority over the entire Taliban movement. With the matter now in the media spotlight, he is expected to harden his stance against internal challengers,” says Mehsud.

If battle lines are drawn, the supreme leader is likely to side with Sirajuddin. “Tensions are likely to rise with Mullah Baradar and Mullah Yaqoob. Baradar, a former close confidante of Mullah Omar, sees himself as a rightful successor. Conversely, Sirajuddin commands immense respect due to the Haqqani family’s sacrifices over the past 20 years and his spiritual influence. Problems are therefore expected mainly with the Kandahari group of Baradar and Yaqoob,” he adds.

Denials & resistance

Taliban chief spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid has dismissed reports of discord as “unauthentic and fabricated lies,” claiming that they were based on misinterpretations of the Amirul Momineen’s directives.

“The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan faces no rifts within its ranks. All members follow the same leadership that runs the system,” he adds. “For over two decades, there have been attempts to sow divisions, labeling factions as Haqqani, Kandahari, Quetta Shura, Peshawar Shura, or Waziristan Shura. All such attempts have failed.”

An adviser to Sirajuddin also released an audio clip, purportedly from one of his recent speeches, in which the interior minister praised Hibatullah’s leadership, crediting him with helping the country overcome myriad challenges over the past six years. “When hearts are illuminated by the light of faith, what can the darkness of power and politics do to make anyone lose their way?” he says.

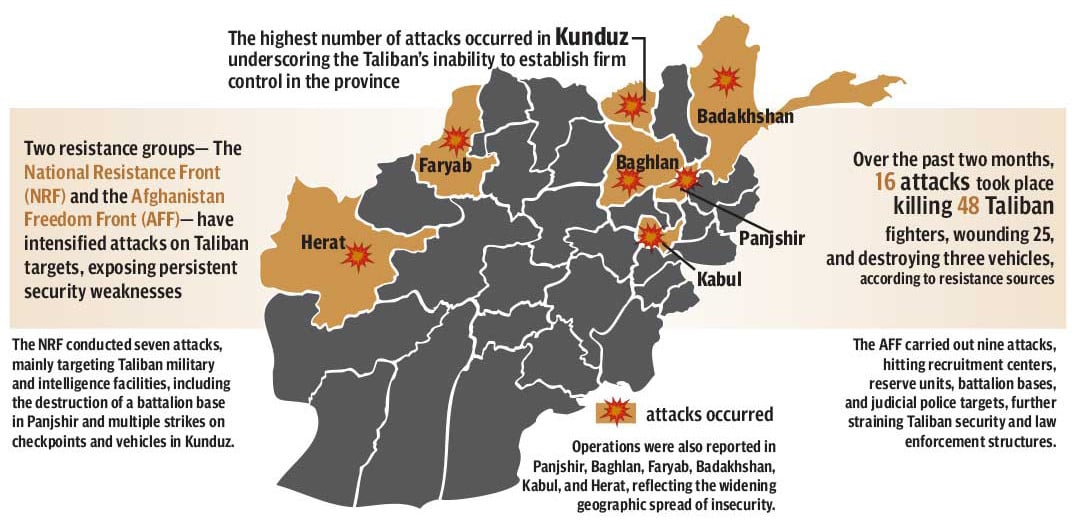

These official denials aside, reports of divisions within the Taliban theocracy have emboldened non-Pashtun armed groups to capitalise on the situation. The National Resistance Front (NRF) and the Afghanistan Freedom Front (AFF) have stepped up attacks on Taliban targets, exposing chinks in the regime’s armor.

In December 2025 alone, the two groups carried out 16 attacks, killing over four dozen Taliban fighters, according to a tally maintained by these groups. The attacks were carried out in the provinces of Kunduz, Panjshir, Baghlan, Faryab, Badakhshan, Herat, and even in Kabul, casting doubts on the Taliban regime’s claim of establishing its writ across the country.

Regional shockwaves

Should tensions escalate into open conflict, transnational groups based in Afghan safe havens could join the fray, likely siding with the supreme leader, to whom they have pledged their allegiance.

“If it becomes clear that these differences are heading toward armed confrontation, other transnational militant groups in Afghanistan will naturally also react,” says Mehsud.

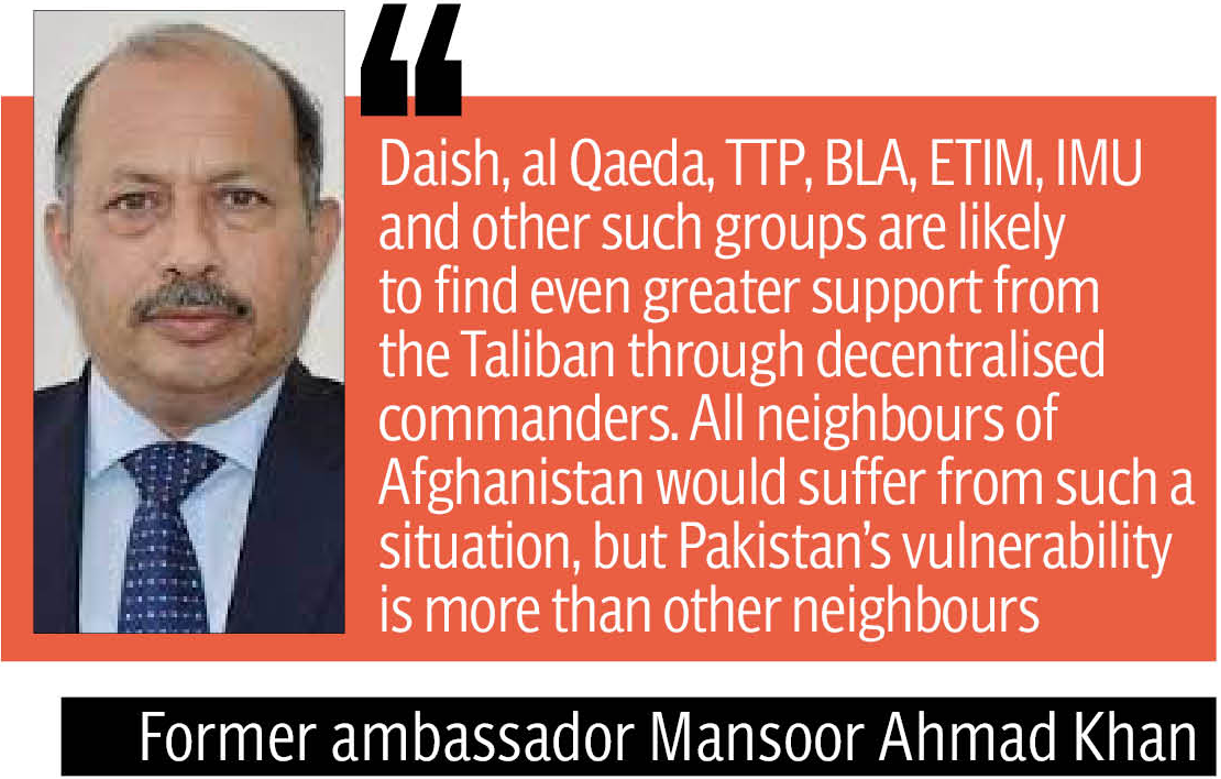

If this happens, Afghanistan could descend into a civil war reminiscent of the 1990s, with neither its neighbours nor the wider region immune to the fallout. “Daish, al Qaeda, TTP, BLA, ETIM, IMU and other such groups are likely to find even greater support from the Taliban through decentralised commanders. All neighbours of Afghanistan would suffer from such a situation, but Pakistan’s vulnerability is more than other neighbours,” says ambassador Mansoor.

Pakistan shouldn’t allow itself to be drawn into this quagmire, he warns. “It is important for Pakistan to let Afghans handle their internal political affairs. Pakistan should remain engaged with the Kabul government regardless of Afghanistan’s internal developments.”

Inam, however, warns that Islamabad cannot remain a silent spectator, as any conflict in Afghanistan could spill over, endangering Pakistan’s security and stability.

The supreme leader’s warning was not rhetorical flourish; it was an admission of vulnerability. Beneath the rigid discipline and religious authority of the Emirate lie unresolved factional rivalries, tribal fault lines, and a growing resentment over corruption and monopolisation of power.

While Mullah Hibatullah continues to rule through centralised control and spiritual legitimacy, the widening gulf between Kandahari hardliners and Haqqani pragmatists, compounded by the marginalisation of non-Pashtun groups, is threatening the regime’s cohesion. For now, force, fear, and faith hold the system together. But these are brittle instruments of governance.

As resistance groups intensify attacks, transnational militant outfits look for openings, and regional actors hedge against instability, the cost of internal paralysis will only rise. Without serious introspection and course correction, the Emirate may discover that a battlefield victory is no guarantee of survival in peace — and that the gravest threat to its rule comes not from without, but from within