PUBLISHED

February 22, 2026

PESHWAR:

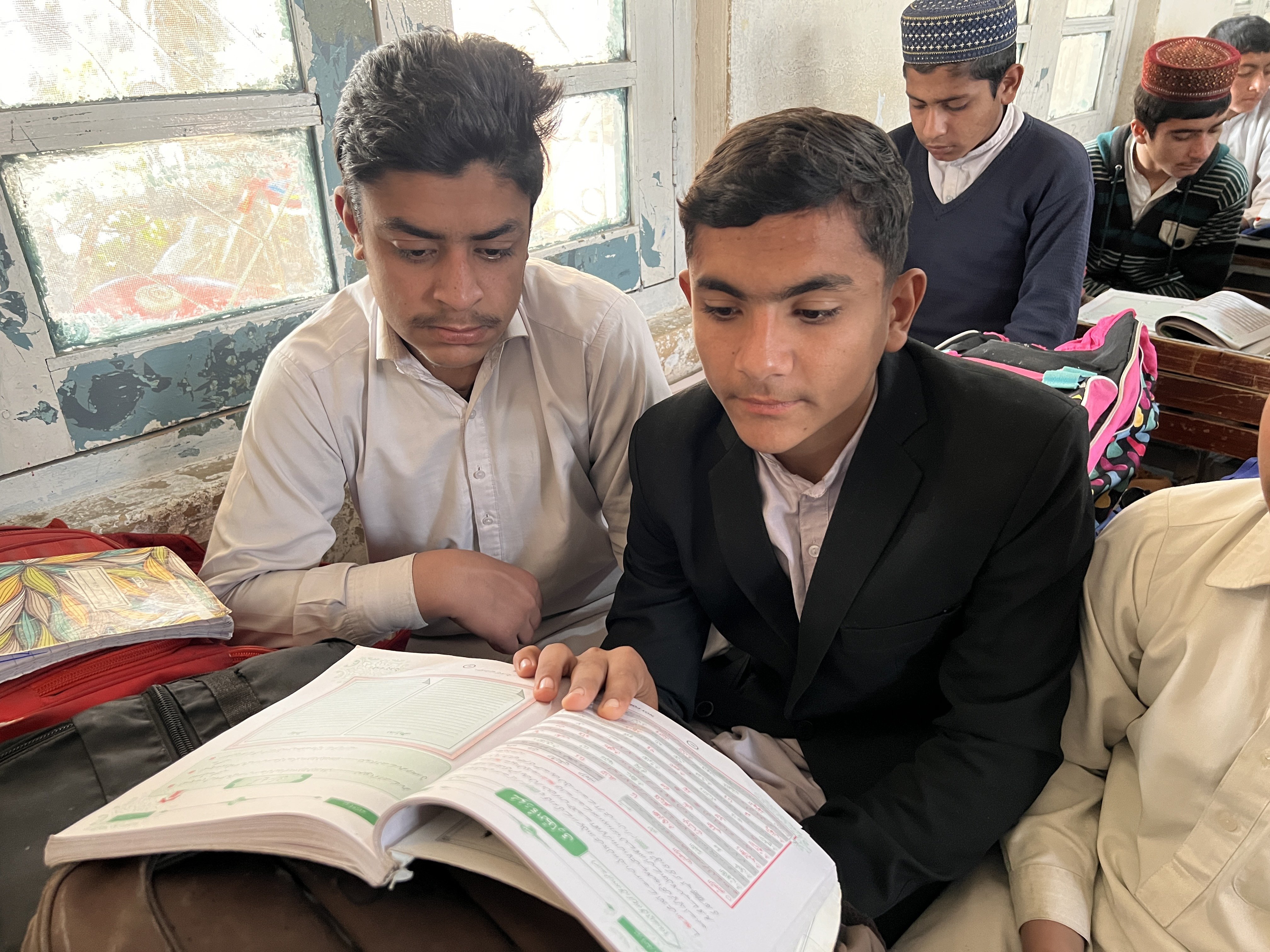

Every day, 15-year-old Mashal Khan, a sixth-grade student, walks three kilometres from his home to his government high school in Jalala. The journey takes him longer than other children and is especially arduous because he was born with disability in both feet.

“It is very difficult for me to reach school on time and I try to start out earlier than other children,” says Mashal. “But on rainy days, I cannot attend school and miss classes because walking on slushy ground is dangerous for me.”

Mashal’s father is a mason whose earnings hardly meet the expenses of his family, so he cannot afford to buy Mashal a wheelchair.

Regarding accessibility for children with special needs, Mashal says there is no dedicated washroom for students with disabilities. He finds it difficult to use the school’s washrooms because they are located at an elevated level.

Umar Ghani was born with a spinal condition that caused paralysis in one of his legs. However, now 33, he holds a bachelor’s degree and completed his education despite his disability. Ghani, a resident of Gunjai village in Mardan district, says, “From primary school to college, accessibility in educational institutions was a constant challenge for me, but I did not give up.”

He added that his aim was to secure a government job, but due to the high rate of unemployment, political influence in recruitment and limited vacancies in various departments, he failed to find employment and now runs a grocery store near his home.

He believes that people with disabilities should not be discouraged from pursuing education or developing skills, as through hard work they can achieve their goals with dignity rather than depend on others in society.

According to the Special Life Foundation, an organisation working for the rights of persons with disabilities in K-P, almost 98 percent of government-run schools are inaccessible for special needs children, forcing most of them to stay at home without education.

Zawar Noor, chairman of the organisation, told The Express Tribune, “Although the Building Accessibility Code 2006 makes it mandatory for every government and private building to be accessible for persons with disabilities and to have ramps and washrooms for wheelchair users, the law is still not implemented.”

He said that the education of about 90 percent of children with disabilities was affected by inaccessibility, while the remaining 10 percent were those living in major cities with access to separate special educational institutions.

He added that he had raised the issue with the Education Department but it still has not been addressed.

According to the 2023 Census, K-P has about 1.29 million people with disabilities, representing 3.16 percent of the population. Of these, around 11.16 lakh (87%) live in rural areas, while the remaining 1.69 lakh (13%) reside in urban areas.

Zawar believes that the number of persons with disabilities is much higher than reported in the latest census. Referring to World Health Organisation and World Bank reports, he mentioned that there are about four million persons with disabilities across the province.

“Across the province few special education complexes and institutions are established where almost 2,000 to 2,500 students are enrolled while the remaining special children are denied their right to education,” he says.

The Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR) at the Institute of Management Sciences, Peshawar (IMSciences), is currently conducting a study to promote equity in budgeting for elementary and secondary education (E&SE) in K-P.

One of the key objectives of this initiative is to ensure equitable access to education and opportunities for vulnerable groups, including children with disabilities, girls, the transgender community, and refugees.

Dr Zafar Zaheer, Coordinator at the centre, confirmed that approximately Rs 363 billion has been allocated for elementary and secondary education for the 2025-26 fiscal year, adding that the share of the development budget is relatively low.

He said that the allocated budget is insufficient for the enrollment of 4.9 million out-of-school children, adding that the government needs to prioritise basic education, provide more financial support, and strengthen monitoring and teachers’ capacity to overcome these challenges.

“About 80 percent of the province’s population lives in rural areas, where dropout rates are high because children face difficulties accessing schools,” Dr Zaheer highlights. ““In these areas, vulnerable groups face severe hardships. For example, persons with disabilities do not have accessible infrastructure in schools, and girls face cultural barriers and security challenges.”

To increase school enrollment and address these challenges, he stressed that the government needs to allocate the education budget on an equity basis and attract more international donors to provide technical and financial support to the education system.

Naghmana Sardar, Director of Elementary and Secondary Education K-P, says that the government had made its best efforts to enroll children who were of school-going age but not attending classes. She added that for this purpose, enrollment campaigns were being carried out throughout the year.

According to Sardar, accessibility issues were being addressed, alternative learning programmes had also been launched, and a large number of out-of-school and dropout children had been admitted to schools.

“In areas where primary schools exist but middle schools are lacking, or where schools are overcrowded, double shift schooling has been introduced in existing buildings, which has proven to be a successful step,” she says. “Monthly stipends are also provided to girl students, linked to their attendance and performance, which has helped attract them to education.”

Regarding accessibility for children with disabilities, she said that the new schools are being built with facilities such as ramps, special washrooms, and other necessary amenities. Also in existing school buildings, these facilities are being provided whenever there is construction of additional classrooms or other infrastructure, to facilitate children with disabilities.

The data from K-P’s Social Welfare Department shows 57 government-run educational institutions established in different areas of the province, including the newly merged districts, where 3,950 special children are enrolled.

Talking to The Express Tribune, Rizwan Ahmad, deputy director Special Education Complex Peshawar, said that according to the Benazir Income Support Programme, the number of children with disabilities in K-P stands at 370,000, aged between one and 18 years.

Talking to The Express Tribune, Rizwan Ahmad, deputy director Special Education Complex Peshawar, said that according to the Benazir Income Support Programme, the number of children with disabilities in K-P stands at 370,000, aged between one and 18 years.

He added that children with physical disabilities, visual impairments, hearing and speech impairments and intellectual disabilities are currently receiving education at those institutions.

“Among children with disabilities, the enrolment ratio is 1:3, meaning that for every one girl, three boys are admitted to educational institutions,” he says. “The disparity in enrolment is largely due to taboos and cultural barriers.”

Regarding budget allocation, he said that most of the budget for those institutions was spent on staff salaries, adding the remaining portion was utilised for students in hostels and for providing pick and drop services free of charge. “We have a separate mandate from the Elementary and Secondary Education Department, but we provide technical and other support to it,” he adds. “Last year, 25,000 special needs children were enrolled in regular schools, and this year the number has reached around 30,000 students.”

Sajjad Aziz, 17, a resident of Jalala village in Mardan district, belongs to a poor family, said that he became paralysed because of polio at an early age and was forced to leave school in the second grade due to lack of facilities, including special washrooms and ramps for children with disabilities in both public and private schools in nearby areas.

It was his dream to obtain a graduation degree, but due to financial issues and the hardships he faced at school, he had to discontinue his education. He now helps his father at a general store.

On condition of anonymity, an official from the Elementary and Secondary Education Department said that six-room schools constructed after 2013 were made accessible to children with disabilities, while two-room schools built earlier lacked such facilities.

“There is no available data showing how many government-run schools are accessible to special children,” explained the official. “Of some 33,000 schools in K-P, only about 300 to 400 have such facilities. No specific budget is allocated for these facilities. Facilities are provided in newly built schools and institutions where new classrooms are constructed through a fully allocated budget.”

Despite Article 25-A of the Constitution guaranteeing free and quality education for every child, millions across Pakistan remain out of school. Unicef estimates that 25.1 million children aged five to 16—around 35 per cent of this age group—are not attending school, while official data shows that 4.9 million children in K-P alone are out of school, with girls most affected. For children with disabilities, however, the crisis is even more severe, as they must navigate not only poverty and weak education systems but also inaccessible school buildings, a lack of specialised facilities, mobility challenges, and persistent social stigma that further limits their chances of staying in education.

Peshawar-based child-rights activist Imran Takkar stressed that free and quality education is a constitutional right and that laws exist in all four provinces, yet inadequate budgets, low government priority, limited community awareness, harsh economic conditions, and outdated curricula continue to keep children away from school.

For children with disabilities, these systemic failures translate into even deeper exclusion, underscoring the urgent need for inclusive infrastructure, accessible facilities, and targeted institutional support. Had such systems been meaningfully in place, individuals like Umar might not have been forced to rely on small self-employment for survival, but could instead have pursued stable professional opportunities in offices and other skilled, white-collar roles—contributing to society in ways their education had prepared them for.

Abdur Razzaq is a Peshawar-based multimedia journalist. He tweets @TheAbdurRazzaq

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer