PUBLISHED

February 22, 2026

It is rare for a fiction writer to portray his city and its crushed inhabitants in a manner that allows an entirely new world to emerge before the reader. A world that, despite its resemblance to the reader’s own city and neighbourhoods, carries a subtle sense of unfamiliarity, prompting the reader to feel as if he is entering a magical forest or the unknown.

Iqbal Khursheed has accomplished this. He has rendered the last three to four decades of blood-stained Karachi, the Karachi that exists in reality, with such clarity and craft that a seasoned writer like Irfan Javed has described Khursheed as a chronicler of truth.

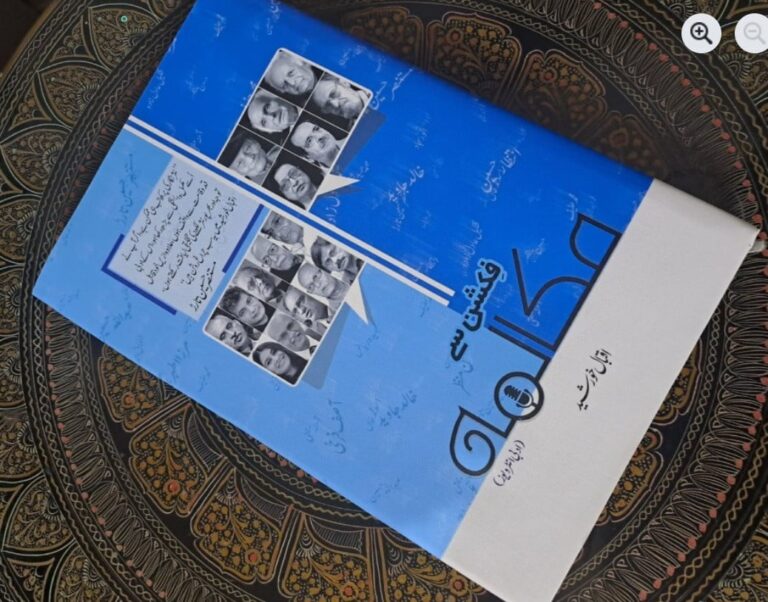

Khursheed has already established himself as a fiction writer, journalist, interviewer and film critic. In his latest book Chhinal Aur Degar Afsanay, he appears to take a fresh leap as a fiction writer. This leap carries a sense of renewal, yet it is not a rebellion against tradition. Rather, it is a rediscovery of it.

The stories portray age-old human concerns such as the complex relationship between men and women, the bitter bond between power and weakness, and a society divided along class lines. Alongside a strong sense of narrative and storytelling, the book also reflects mature experiments in technique and style, making it a work that speaks for a distinctly modern sensibility.

Because of these experiments in technique and style, Ahsan Saleem, a leading poet of prose poetry and editor of the literary journal Ijra, described Khursheed’s stories as so gripping that they leave the reader breathless. He also saw Khursheed’s style as a return to the manner of Rajinder Singh Bedi. This assessment feels justified, as Iqbal’s prose is mature and tightly woven. His sentences are brief yet sharp, marked by a measured or bold choice of words, and infused with the linguistic flavour of Karachi’s middle and working classes, a quality that lends his writing a distinct identity.

At the same time, there is a sense of freshness in the structure of his sentences. At places, one encounters sentences made up of just a single word. In this way, the style becomes Iqbal’s signature. This is clearly evident in his stories such as Cake Aur Kuttay, Mako Dada Ki Asateer, and Stage Dancer.

On the other hand, there are creative experiments with style and form in his work that surprise the reader and encourage them to rise above the level of an ordinary, conventional reader. While such experimentation can be seen throughout the book, the final story, Man o Tu, stands out as a significant instance of creative daring.

Here, Iqbal adopts the forms of modern fiction and infuses them with his own touch of madness, breaking several established conventions of storytelling. A similar approach is evident in stories like Ek Pagal Kahani and Stage Dancer.

Typically, a fiction reader is drawn primarily to characters and events, and these elements reach their peak in Iqbal’s other stories such as Chand Mamoon and Sard Khane Ka Mulazim. However, these are not ordinary incidents.

In these stories, the language appears simple on the surface, yet beneath lies a subtle complexity. Exaggeration and detachment—two seemingly opposing qualities—are handled with remarkable skill, a point noted by the renowned critic and poet Rafiullah Mian in his essay. The effect is genuinely striking. Opposing elements such as darkness and light, joy and sorrow, anxiety and calm are often woven into a single sentence, through which Iqbal challenges the conventional hierarchy of binary oppositions.

One aspect that critics should pay particular attention to is the irony and sharp humour present in the book. At its core, these are stories of the oppressed classes and their sorrows, yet instead of turning them into a tragedy, Iqbal infuses them with life through his dark humour and enduring characters. This is why, whether it is Chand Mamoon or Mako Dada, these characters linger in the reader’s mind long after the story ends.

Overall, this is a fresh attempt to portray Karachi’s oppressed classes with solid craft, powerful style, and full command of technique – an effort rarely seen in the past. In fact, this anthology deserves to reach non-Urdu readers and dissolve borders.

It captures the Karachi of the last 40 years, a city that very few have observed with such empathy, anguish, and wit. Those who have chronicled the elegy of this Karachi can be counted on one hand, and with this book, Khursheed stands out as the most prominent among them.

The writer is a freelance contributor

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer