Francis Newton Souza was already a major figure in the Bombay art fraternity, and had developed a considerable following by 1949, when his paintings were featured in an exhibition at the Indian Art Society. Several visitors asked about his work, but not everyone was satisfied. Within days, his “obscene” artwork, including a nude self-portrait, was seized. He was left in both locations as his studio was raided by police looking for pornographic material on suspicion of obscenity. be enraged and despised.

Although not immune to censorship and controversy, the incident reaffirmed Souza’s determination to reach a more liberal audience. In July 1949, aged 26, he left for London aboard his SS Canton. “After 10 days here, I don’t have much to say. But life in London is a luxury to maintain, elements like water cost pennies, and necessities like toilets… I learned that I need pennies. good friend (Ebrahim) Alkazi was the person with whom I shared a boarding house. Otherwise, I would be in desperate financial difficulty. Therefore, with enthusiasm comes responsibility. I learned a bitter lesson. “He who never has hope can never despair,” Sousa recalled in a letter to members of the Progressive Artists Group dated August 17, 1949. Letters between Haider Raza and his Artist Friends (published in the Raza Foundation). Then he presented his first solo work in the city at Gallery His One in 1955, five years later, and it was sold out. This work received as much critical acclaim as his autobiographical essay, “Maggot Nirvana,” published in Encounter magazine in the same year.

Often described as the formidable child of Indian art, which rebelled against social and artistic conventions and sought to break new ground, the country lost arguably one of its most provocative modernists to London. . But for Souza, it was a journey into the unknown that opened up a new world. “He was a man who not only traveled as things happened, but guided his own career, life and way of thinking. He knew himself very well,” said his friend and artist Krishen. Khanna recalls.Director Uday Jain Doumimaru Gallery On April 12th this year, to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth, an exhibition entitled “Sousa’s Reminiscences: Iconoclastic Visions: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Francis Newton” added: His use of line and color was equally confident, even when most artists, including him, were still trying to find their own style. ”

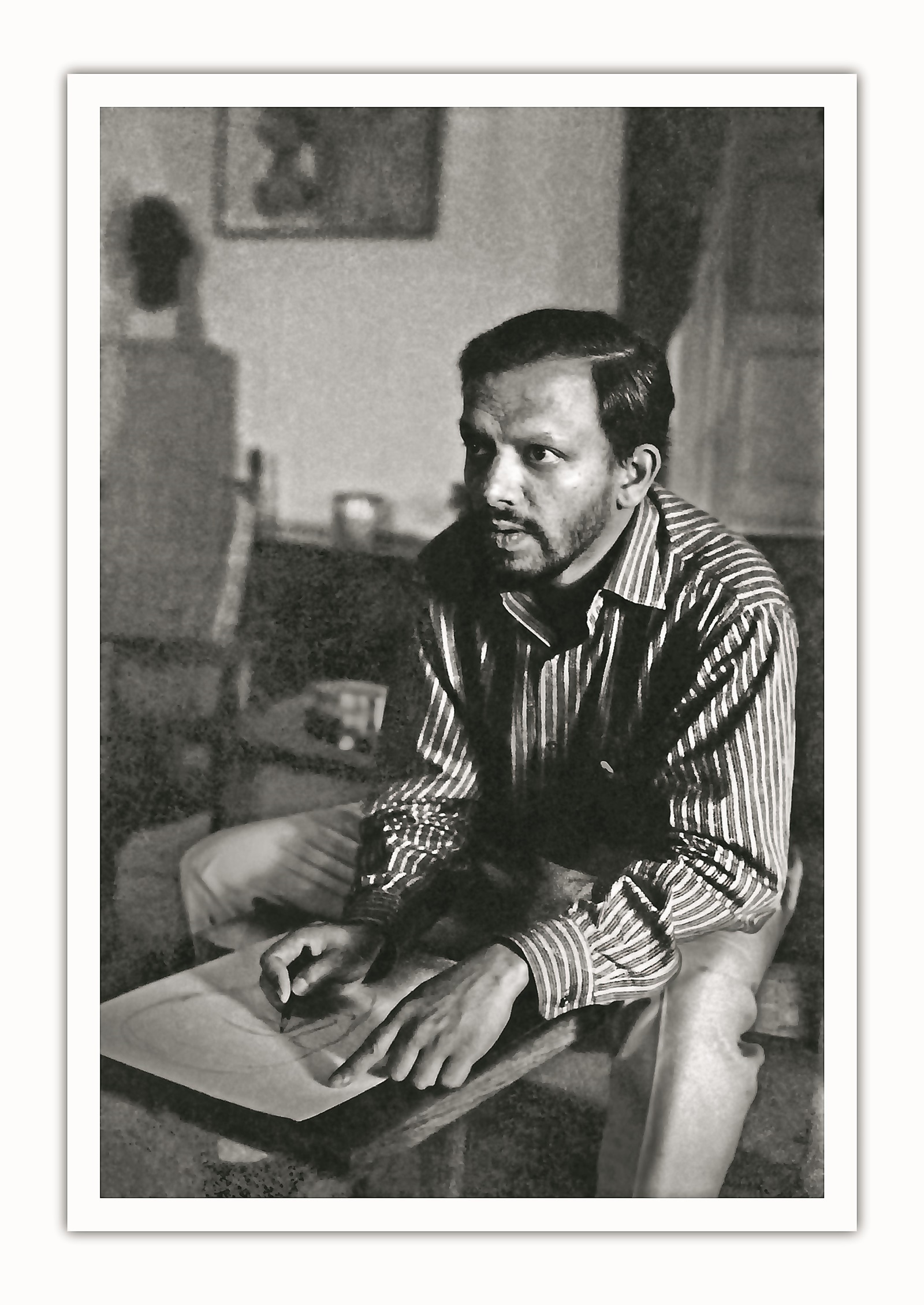

Portrait of FN Souza (1962) by artist photographer Jyoti Bhatt (Courtesy of Jyoti Bhatt and Asian Art Archive)

Portrait of FN Souza (1962) by artist photographer Jyoti Bhatt (Courtesy of Jyoti Bhatt and Asian Art Archive)

Raised in the idyllic village of Saligao in northern Goa, Souza was just a toddler when his father, English teacher Jose Victor Aniceto de Souza, died, followed by his sister. His debt-ridden mother, Lilia Maria Cecilia Antunes, had just moved to Mumbai for a job as a dressmaker when Souza suffered a severe attack of smallpox. His miraculous recovery led to the addition of Francis to his name in gratitude to St. Francis, the patron saint of Goa, but his mother did not wish her son to become a Jesuit. He also decided to live as a priest. What she didn’t know was how unlikeable Souza was with his demeanor. free-spirited temperament And if you have artistic inclinations, you may be suited for such a life. She enrolled him in St. Xavier High School, but he was expelled after two years for sketching pornographic pictures in the bathroom. At the age of 16, he entered the Sir J. J. School of Art, where he too was suspended for participating in the Quit India movement. Returning home, he was furious and painted what would become one of his seminal works, “The Blue Lady,” an azure nude painted with a palette knife. Regarding his disappointment with his formal education, Sousa wrote in the catalog of his 1948 exhibition at the Bombay Art Society: The teachers were incompetent… Shelley was expelled once, Van Gogh was expelled once… I was expelled twice. Rebellious boys like me had to be fired by principals and school directors who instinctively feared we would upset the apple cart. ”

But he soon finds himself in the bustling city of Bombay among a group of artists, writers, and poets intent on discovering an avant-garde modernist aesthetic for independent India. became. Under the umbrella of the Progressive Artists Group, which emerged a few months after India gained freedom, individual ambitions found collective meaning. With Souza as secretary, the heterogeneous group comprised founding members SH Raza, HA Gade, KH Ara, Sadanand Bakre and MF Hussain. “We bonded through a magical chemistry. We would talk all night. We would often go to the Back Bay and sit and think about what art should be and how it should be done. We kept talking about how it should be done. Without looking at any models of art…without actually doing it, we first formulated it in speeches,” Souza told The Patriot in 1984. .

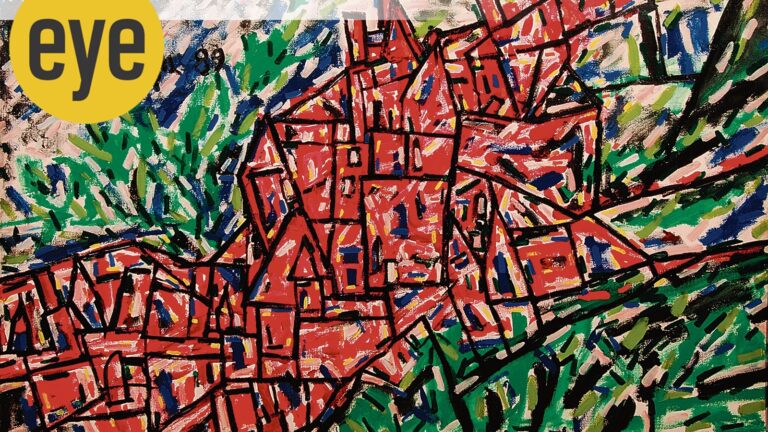

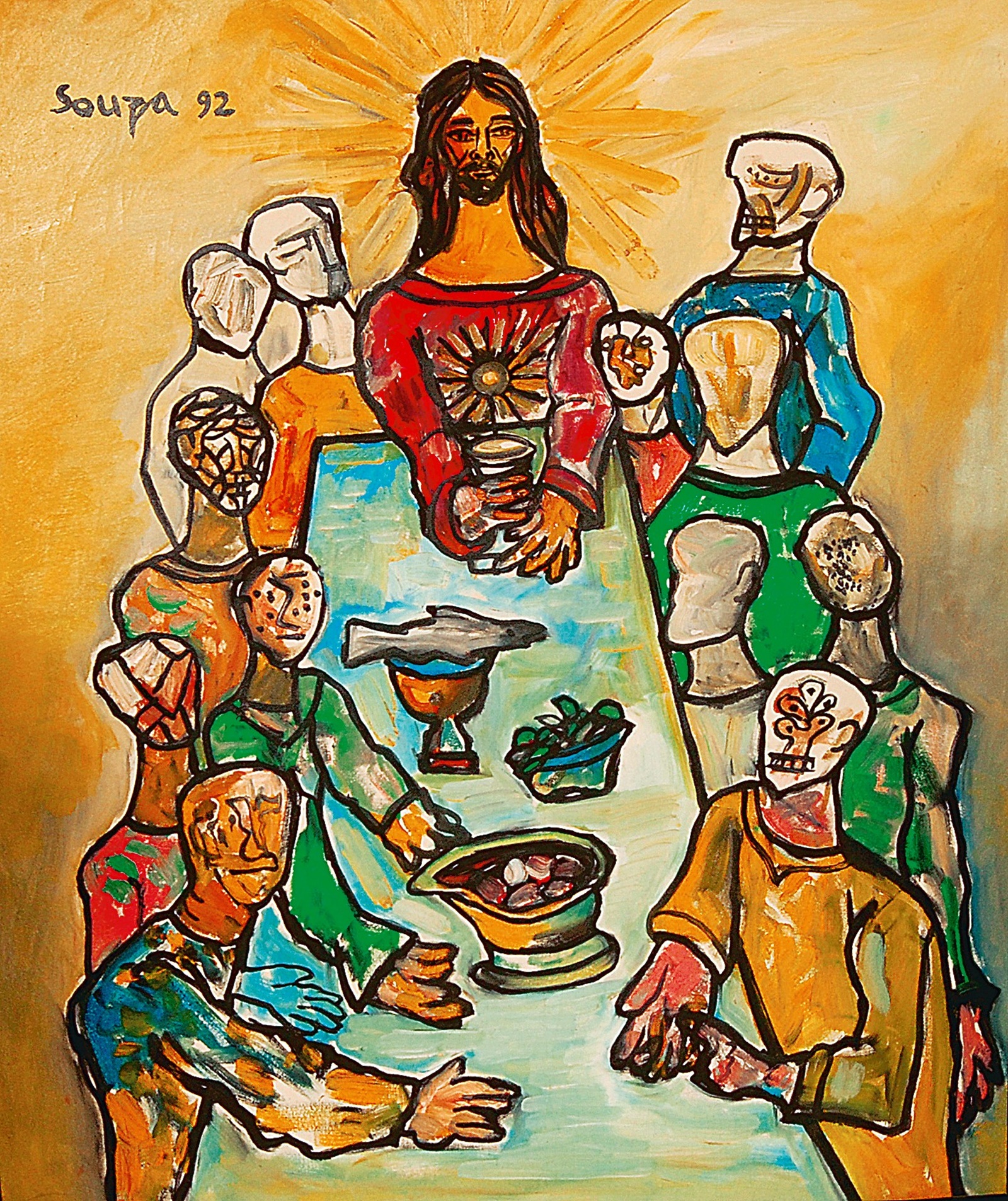

While each artist seemed to incorporate new learnings into their work, Sousa’s changes included less communist leanings and more pronounced strong lines and brushstrokes. From the early ’40s through his ’50s, some of the diverse influences that shaped his art began to surface, including South Indian bronzes and temple carvings. From Khajuraho to European Modernism. The landscapes he admired in his native Goa take the form of lush horizons on his canvases, as do the visual culture of the Catholic Church and the stories of tortured saints told by his grandmother. It emerged as an icon. Distorted figures and grotesque heads would remain a permanent part of his work, transcending medium and metaphor.

Souza’s Untitled (1992) (Courtesy of Dhoomimal Gallery)

Souza’s Untitled (1992) (Courtesy of Dhoomimal Gallery)

My first few years in Europe were filled with anxiety. In the country, which is still recovering from the devastation of World War II, Souza’s wife, Maria, was initially the breadwinner. He became familiar with Western art through museums and galleries, where he encountered works by Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and Pablo Picasso. Although he sometimes received some income from his writing and commissions, including a mural for the Indian Students’ Office in West Cromwell Street through the Indian High Commissioner VK Krishna Menon in 1950, he did not begin to gain recognition. This is from his first solo work in 1955. From 1956 onwards, his regular monthly salary for four years from American collector Harold Kovner provided him with a secure livelihood. During his next decade, he earned respect in literary circles, producing some of his most revered works, including the monochrome painting “Black on Black” and his 1959 collection of writings and paintings, “Words & Lines.” Ta. His 1955 canvas “Birth,” depicting a pregnant nude body, himself in a priest’s tunic, and a city scene, set the world record for the most expensive Indian painting of all time in 2008, and its price It was 2.5 million USD. In 2015, Birth was resold for US$4.8 million.

Even as Sousa and his art traveled the world (representing Great Britain at the Guggenheim Prize in 1958 and winning a scholarship to represent Italy in 1960), his home life was in turmoil. He became an alcoholic to the point that it interfered with his work, but he finally decided to seek help in 1960. He also had a turbulent affair with Jewish actress Liselotte Christian, with whom he had three daughters. After that relationship ended, he married 17-year-old British-American Barbara Zincant. The couple traveled to India and upon their return moved their base to New York in 1967. Mimicking his state of mind, his visits to the California countryside resulted in cheerful landscapes with vibrant colors. His experiments during this period included “chemical painting,” in which he painted or drew on pages torn from magazines, catalogs, and printed photographs using chemicals that dissolved printer ink. “He was also a great writer and a voracious reader of art history, poetry and philosophy, which is reflected in his work,” says founder RN Singh. progressive art gallery. He feels that the artist was quite misunderstood as brash and self-centered. “He may have been unpredictable, but he was also very generous…His work was often personal and influenced by his life experiences. For example, his sensuality… The female nudes may be considered too revealing, but they represented both his love of the female form and his own broken relationships and multiple affairs. It was a way to heal his complex that he felt against women due to his scars, and it was also his rebellion against conventional beauty standards.”

Khanna recalls that the irredeemable Sousa was also very demanding in his relationships. He remembers when he visited London when he wanted to buy Souza’s nude but he didn’t have the asking price of 1,600 rupees. It will be my privilege to own it in 1600,” says Khanna. As friends, they often criticized each other. “I once anonymously wrote an article opposing what he wrote. I commented that he liked himself a little too much, but that’s not true of any writer, painter or musician. That could be dangerous… He read it and laughed. He thought it was written by (lawyer and art lover) Karl Kandaravala, but when I told him it was, he laughed. He didn’t think I could have critical ideas unless I was an art critic.

Despite worldwide fame, there are few exhibitions Some of his works were kept in India until the beginning of this century. “It was only after the auction market took off that a large part of the Indian market took notice of Souza. Also, in contrast to overseas buyers who admired his nude and figurative works, His Devil’s Head remains his most widely loved work,” says Jayne. He further added, “My father, Ravi Jain, held Souza’s first exhibition at Doomimar in 1965 and sold just one work. When Souza asked him why, he was already in Europe. Because he was considered an important artist. Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso — My father said that India will take time to recognize your genius. When we held another exhibition of his work from the 40s in 1975, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was present, as well as important collectors such as Masanori Fukuoka and Ebrahim Alkazi. When he exhibited his work at the Kara His Mela in 1986, he also did a live his painting, which was a big hit with the students who gathered to get autographs. ”

Painting with absolute freedom, Souza’s art, like his own rebellion, remained perplexing and captivating. An outsider at heart, he had few friends when he died in Mumbai in 2002. After his death, Khanna, who received praise from Britain and India for his modernism, said that Sousa truly believed that he should become an artist. “He never said, “I’m a great painter,” but he was a great painter and acted like one. I supported what they were doing,” Khanna added.