Volunteers rose early in the morning to erect knee-high American flags on Freeport’s main street, and snipers kept watch from rooftops as mourners gathered to remember his life ahead of his private funeral on Friday.

Comperatore, who celebrated his 50th birthday last month, grew up in a working-class community along the Allegheny River, graduated from Freeport High School, home of the Yellow Jackets, and married a former classmate, Helen, and together they raised two daughters.

“He was the quintessential family man and father to the most amazing daughters,” his obituary said.

His cousin, Cindy Villela, 58, admired his fatherly nature: When she thinks of Mr. Comperatore, she thinks of a doting father.

“Just genuine and caring,” she said as she walked to the congregation.

She summed up her feelings in one word: “shocked.”

Comperatore worked at a plastics plant in the forested hills of Butler County for nearly 30 years, rising from maintenance supervisor to project engineer. In his spare time, he served in the U.S. Army Reserves and was a volunteer firefighter.

Fire engines flanked a black van carrying Comperatore’s body along country roads to Laube Hall. Christina Moss, 44, said she was moved by the show of solidarity.

Flowers were also delivered in large numbers — the craft store owner noted that the orange and purple roses were particularly beautiful — and as she queued to pay her respects, Moss read a note inside one of the bouquets.

“I don’t know you…” wrote one cheerleader from Texas.

“A lot of people here didn’t know him,” she said, “but the compassion you all feel is really heartfelt.”

Comperatore’s Christian faith guided his life, according to his obituary. Every Sunday, he worshipped at Cabot Church, then went hunting, fishing and walking his two Dobermans, his brother, Steve Warheit, said.

MAGA politics was another passion of his. Warheit said he loved Trump and was excited to attend Saturday’s rally. A few minutes after Trump’s speech began, gunfire shattered the joy. Comperatore threw himself on top of his wife and daughters and died trying to protect them, Herren told Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro (D).

“Corey was the best of us,” Shapiro said at a news conference this week near the Butler Farm Show, a rural venue known for tractor-pulling contests and funnel cakes before the assassination attempt.

The gunman who was shot dead at the scene was a 20-year-old man who had driven from the Pittsburgh area. Suspect Thomas Matthew Crooks, a Republican, climbed to the roof of the American Glass Research building outside the rally’s security perimeter and crouched on the sloping roof with an AR-type rifle. Authorities said the suspect fired eight shots, killing Comperatore, severely wounding two other spectators and striking Trump in the right ear.

Three days later, Trump contacted Comperatore’s widow to ask how she was, she wrote on Facebook. (She told the New York Post that Biden had called first.) Her husband’s political views.

“He was very gracious,” she wrote of Trump, “and said he would continue to call me in the coming days and weeks.”

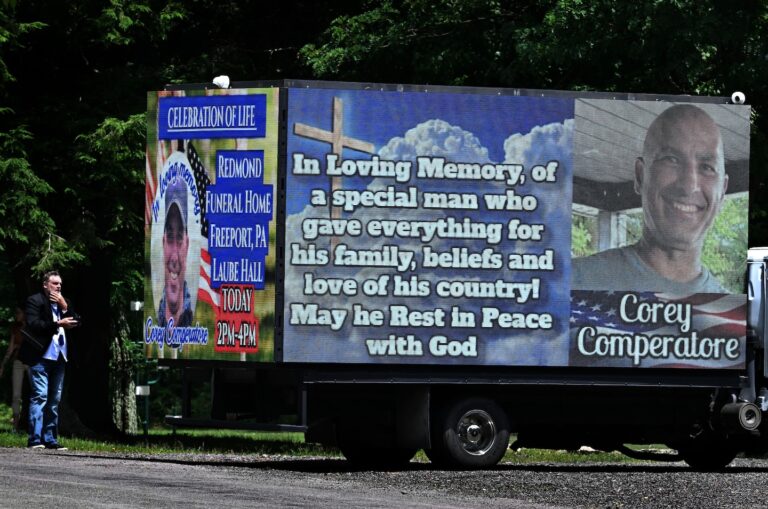

Helen asked Lt. Col. John Placek, 76, to set up a special electronic sign outside Thursday’s rally, he said, looking at his creation. (People in town know he owns several electronic signs, he added.)

“Praying for Corey Comperatore and his family,” the sign featured a photo of Comperatore and an illustration of Jesus Christ with his hand on President Trump’s shoulder.

“For something like this to happen,” Placek said, pausing. “America is in trouble.”

Residents in this Republican stronghold, dotted with Trump signs, have been gathering in churches, restaurants and backyards all week.

They gathered for a candlelight vigil Wednesday night at Lernerville Speedway, a dirt racetrack near Comperatore’s birthplace. Despite the rain, hundreds of people sat in the damp bleachers, clutching votive candles and holding candles. mobile phone.

“This is not a political event,” organizer Kelly McCollough told the crowd. “There is no room for hate here.”

Marissa Timko, a 25-year-old veterinary technician wearing a Buffalo Township Fire Department hoodie, nodded.

She attended the same high school as Comperatore’s daughter, Kaylee, and they were both cheerleaders. One time after a football game, some girls needed a ride home, so Kaylee called her dad.

Timko said she’ll never forget Comperatore arriving in a blue Ford pickup, ready to act as chauffeur, even though the cheerleaders lived in opposite directions.

“He would do anything for his daughters,” she said.

Was they listening to country music that night? Or Christian rock? Timko couldn’t remember, but Kaylee had once told her that Comperatore’s favorite song was “I Can Only Imagine,” a tearjerker by MercyMe about reaching heaven. So as soon as she heard the news, she ordered a piece of glass art depicting those lyrics for her old friend.

Shall we dance for Jesus?

Or are they silent in fear of you?

A few rows back, Jessica Day had her hands together in prayer. Comperatore attended her church, the 48-year-old nurse said. He sat in the pew with his family every Sunday. Day didn’t know him well, but she said she could tell he was devoted to Jesus.

“But even if you don’t believe in God, you can believe in this,” she said, gesturing to the friends, neighbors and strangers who had walked out into the pouring rain.

She was wearing a pink hoodie that she had bought at a fundraiser for a brain-injured teenage boy in town.

“That’s what we do here,” she said. “We come together for each other.”