PUBLISHED

July 13, 2025

KARACHI:

In Karachi, danger doesn’t always lurk in dark alleys or stormy skies — sometimes, it crashes down from above.

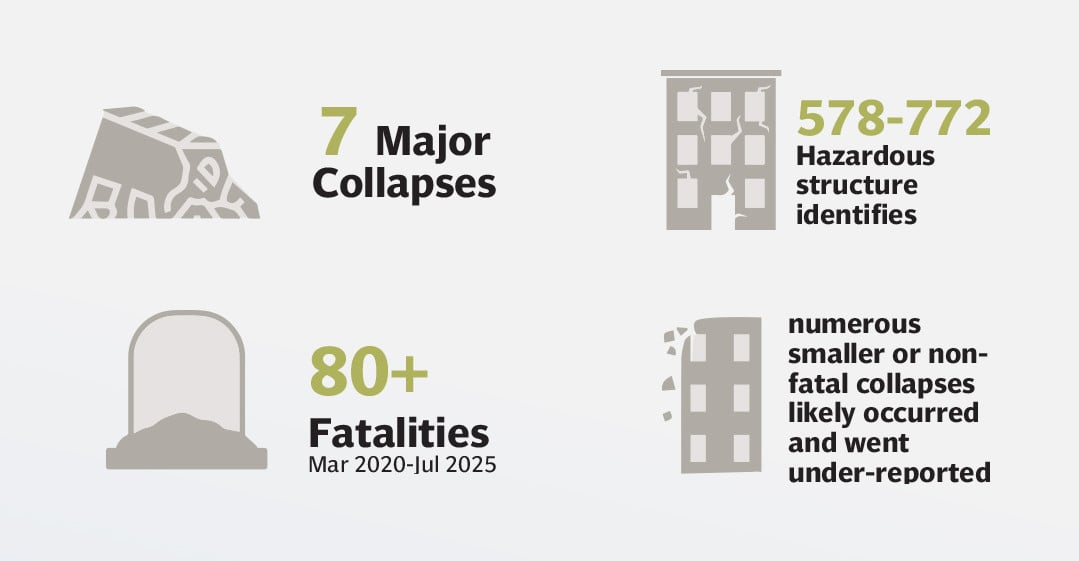

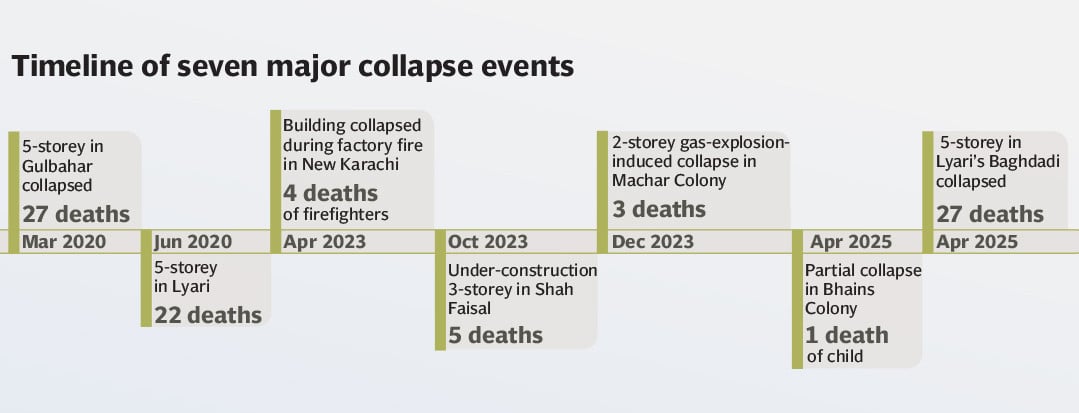

Pakistan’s largest city and economic heartbeat has recently witnessed a disturbing trend: buildings collapsing without warning, turning homes into death traps and lives into statistics. At least seven significant building collapses occurred in Karachi between 2020 and mid-2025, killing over 80 people. These are just the catastrophes that have been publicised or became news headlines because dozens of people lost their lives — there are also innumerable smaller collapses, such as crumbling walls, shattered rooftops, and disintegrating slabs, that happened randomly, fortunately not causing loss of lives, and hence went unreported, uninvestigated, and perhaps still remain unresolved. From the crowded lanes of Lyari to the streets of Saddar that are steeped in tradition, the city’s skyline is decaying. A complex network of corruption, tax regulations, and a profit-driven construction mafia is hidden behind the crumbling facade.

“Their whole life collapsed along with those bricks,” shares Nadeem Shah, a resident of Lyari Baghdadi, who lives two lanes away from the building that collapsed. “For years we have warned the builders from time to time, and even the residents, of all of these illegal constructions, but no one ever paid heed.”

Shah was also of the view that making extra floors is very common, and residents are equally responsible in this as much as builders. “Because of the financial constraints, people keep building floors to accommodate their families when their sons get married, because investing in construction seems better than paying rent for the rest of their lives, especially in low-income areas,” he lamented.

Despite repeated warnings, unauthorised structures continue to rise, and aging residential blocks, some over 70 years old, stand vulnerable to the next rainfall or rogue additions. “In the last five years, all collapses have happened in residential areas with overcrowded neighbourhoods and almost all of them had extra floors built than allowed,” said a former employee at the SBCA, adding that when new construction is done for which the columns/pillars are not ready, and the weight on them increases, it eventually puts pressure on the lower floors and collapses happen.

What’s causing the collapses?

Among the several reasons and factors involving these collapses, there are a few aspects that everyone is aware of and are not to be neglected, such as aging and poorly maintained structures, illegal constructions, additional floors and substandard materials.

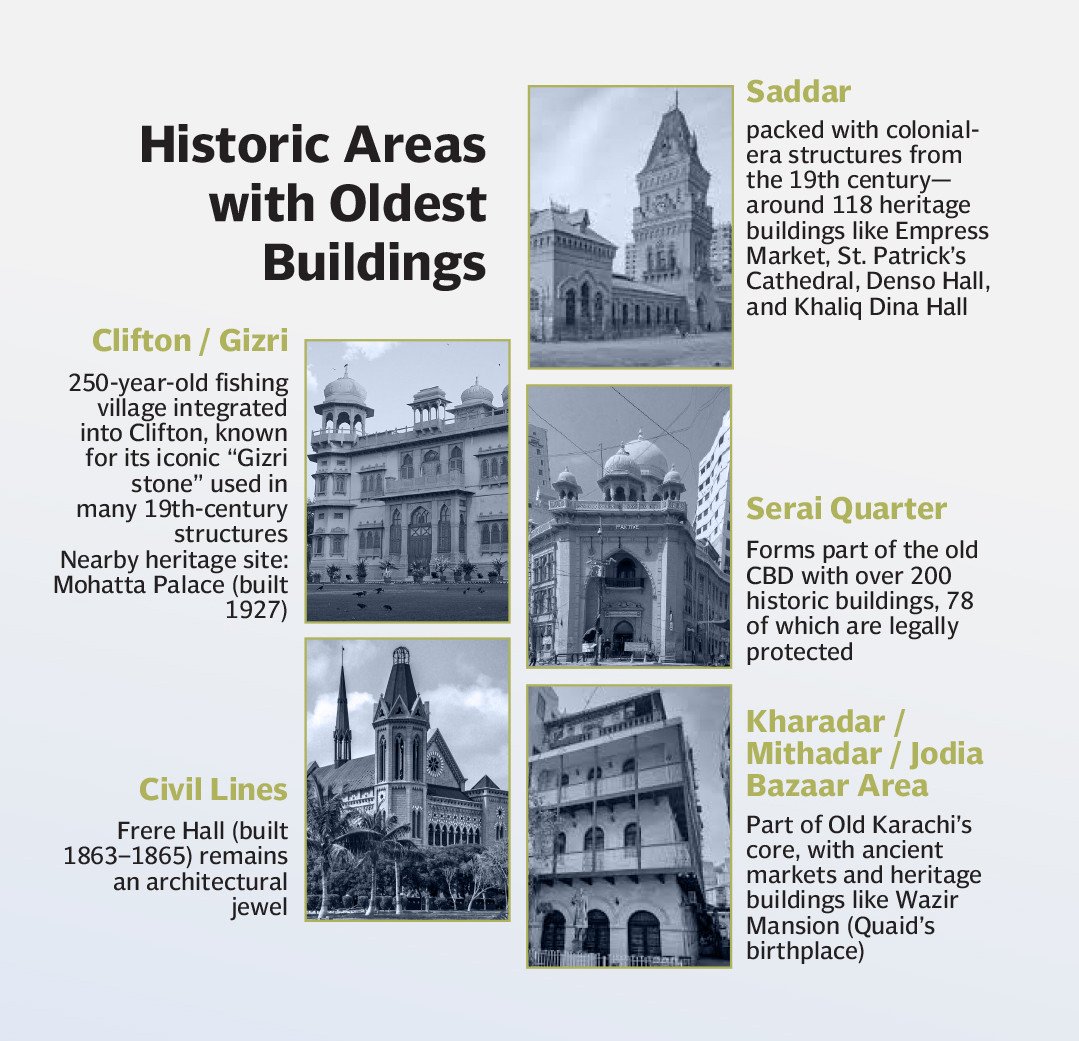

The majority of the structures in Karachi’s Saddar, Kharadar, and Jodia Bazaar neighbourhoods were constructed during the 1940s and 1970s. These structures are crumbling under their weight due to a lack of maintenance. Illegal conversions of two-storey buildings into five-storey flats are occurring; these conversions frequently lack building plans, have poor foundations, and have no safety exits. “Each construction and structure has to be made after a map passed by the SBCA in which they mention floor plans, pillars and even ratio of cement and iron used but majority of the constructors do not follow the map even for cement and iron,” the SBCA officer mentioned adding that there are officers who after acquiring degrees in civil engineering do the calculations, approve these maps and where they find illegal constructions they even take action, but the responsibility here lies with the builders as to what quality they are using.

The usage of weak iron rods, inferior cement, and even salt-mixed sand has been discovered in post-collapse investigations, resulting in dangerously unstable constructions. Karachi lacks a legal framework for regular inspection or certification, in contrast to cities worldwide where structural audits are required by law. “This issue of not following maps and ratio of cement and soil can be resolved for a fraction if the inspectors of each area inspect each construction that has been approved by SBCA, as each area has a designated officer to inspect the buildings,” he suggested.

Rusting and foundation rot are caused by dampness and rainwater seepage, particularly in coastal areas such as Clifton, Keamari, and Gizri.

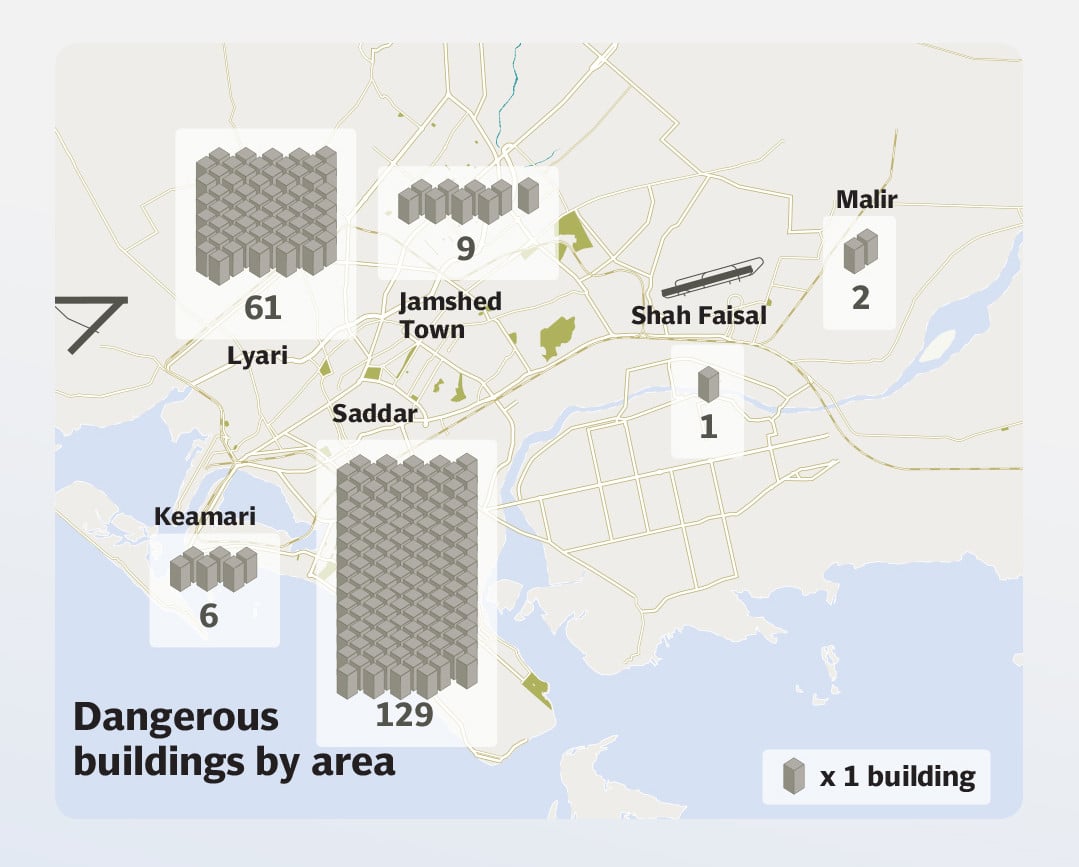

Danger zones

According to the Sindh Building Control Authority (SBCA) and Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), at the heart of Karachi’s collapse crisis is SBCA, which is mandated to approve and oversee building designs. Serious accusations against the agency include lack of accountability after the catastrophe, bribes taken for approvals, fake NOCs, and delayed action against unlawful buildings.

Other than the SBCA and KMC, hand-in-hand work builders and contractors make the very fabric of this city with their architectural responsibilities, but none of them claim the responsibility when a building collapses and there is a loss of lives.

KMC offers municipal supervision and points out unsafe structures, but it lacks the resources and legal authority to take action. These developers, who frequently use frontmen, disappear after selling illegal apartments. The lack of a documented ownership trail in the majority of collapse instances is a legal loophole that renders victims defenceless.

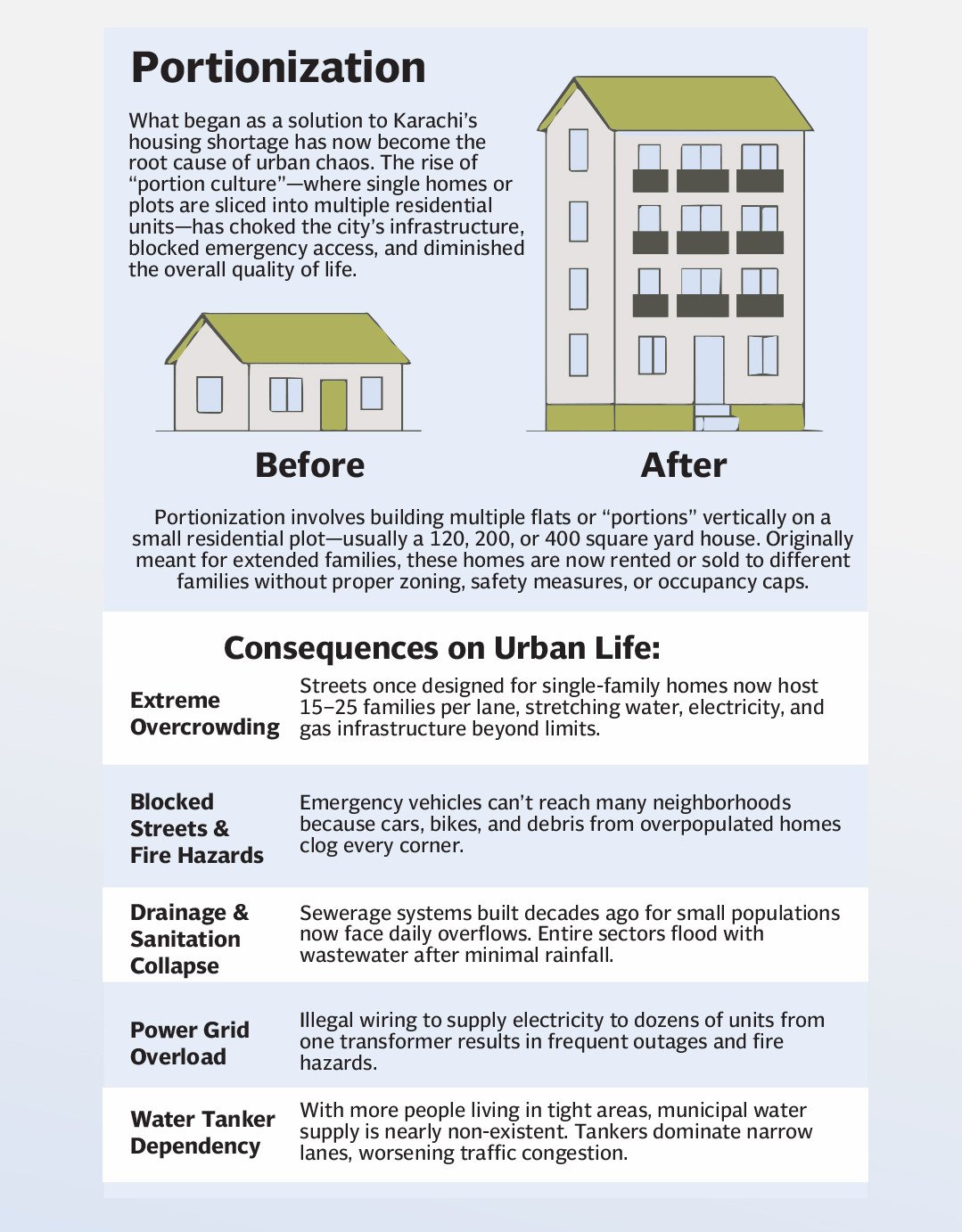

Portion mafia and the rise of vertical slums

Portionisation is an uncontrolled phenomenon that has emerged in Karachi due to the housing demand. “Portions initially seem a good idea to accommodate the increasing population,” shares architect Tauqeer Ahmed. “But it should have been done with proper planning because construction was mainly done in marginalised areas, mostly where each unit was meant to accommodate one family. But now it bears the load of 20-25 families with an increased demand for water, sewerage, parking and other necessities.”

What started as joint-family accommodation has turned into a catastrophe for the city. Plots are converted into multi-storey apartments without any safety, sewage, or structural compliance. In the Federal B. Area, Liaquatabad, North Karachi, Gulistan-e-Jauhar, Korangi, and Gizri/Clifton, these so-called portions are a popular choice. These portions have led to an increase in population, but interestingly, it has resolved the problem of property divisions among a segment of people who couldn’t afford to buy separate places. “I lived with my in-laws in a 120-yard house which was a two-side, corner, west-open plot,” explained Anam Ali. “My husband has three brothers. Three years ago, one of the builders contacted my husband and offered us a hefty amount for the house where he planned to build a six-storey building with two apartments on each floor.”

They accepted his offer, and asked him to reserve a few apartments for them so they could all have their own space. “From the total amount, the builder deducted the cost of four apartments,” she added. “In this way, the four brothers now live separately, so we all have our own houses without having to adjust in a 120-yard house.”

The problem in these constructions right now is that it looks great from the outside, but in the long term, the problem of low-quality construction exists because the builders mostly use low-quality material, and their connection with SBCA and other authorities get them approvals. “They construct five storeys on a two-storey foundation,” says Ahmed. “After that, they pay off officials, and vanish, not worrying about the consequences that people may face later. Each portion built on such constructions costs between 2.5 million to 7 million.”

Evacuation orders don’t do much to help the city’s impoverished. The majority of people refused to vacate when SBCA sent notifications to more than 500 structures before the monsoon season in 2024, alleging a lack of evacuation plans, compensation, and alternative accommodation. “People don’t have anywhere else to go, and they live in that bubble or false belief that the building they live in won’t collapse, which is why such incidents claim lives,” he explains. Other than the builder mafia, SBCA corruption, and portionisation, Karachi’s buildings do not have a computerised registration, history, inspection log, or risk map, which can help in improving the current situation. “Construction maps as old as 70 years are in the record of SBCA, and any investigation on the buildings that collapse can be done accordingly to prove that the cement, soil, iron, and ratio that was approved was used or not,” reveals an SBCA officer.

What should we do?

To curb the menace of buildings, construction, demolitions, maintenance, and bribery surrounding these aspects, the best solution is to digitise the building registry, where a central database with age, structure type, blueprints, and modification history. Other than that, mandatory structural audits can also help in keeping a track of older structures and the quality of these buildings, a law requiring every building to undergo safety checks every 10 years, especially the ones that are over 25 years old.

On the government level, penalties and criminal procedures should be imposed for illegal construction, be it citizens or the builder mafia. Strict jail terms and fines should be imposed for illegal builders, SBCA staff enabling corruption, and contractors using substandard materials. After incidents like recent building collapses, where dozens lost their lives, and the help arrives late due to narrow streets and construction of floors more than allowed, public service campaigns must be organised so that citizens also understand the consequences of building extra floors. Campaigns can also include examples from global cities that are building state-of-the-art constructions, keeping in view their circumstances. Tokyo, for instance, mandates retrofitting of earthquake-prone buildings, Istanbul launched a government-led safety audit and rehabilitation programme, and Singapore enforces strict inspections with legal consequences for non-compliance.

The collapse of buildings in Karachi is a sign of systemic failure rather than an isolated tragedy. Institutional silence, mafias, and corrupt approvals have made homes into death traps. The next collapse is not if, but when, unless authorities do anything about it, not merely send out news releases and notices.