Editor’s Note: This story contains disturbing accounts of sexual violence.

CNN

—

Steve Fishman was still in his teens when he came face-to-face with a serial killer.

At 19, he was hitchhiking from a friend’s place in Boston to Norwich, Connecticut, where he was an intern at a newspaper.

Fishman was not far from his destination and sticking out his thumb when a man pulled over in a green Buick sedan, said his name was “Red,” and told him to hop in. The man appeared friendly and had a balding head with wispy patches of red hair, likely the reason for his nickname.

But as Fishman would learn later, the man harbored a dark secret: His name was Robert Frederick Carr III, and he was a serial killer who preyed on young hitchhikers.

Three years earlier, Carr had raped and strangled two 11-year-old boys and a 16-year-old girl who’d hitched a ride with him in the Miami area. When he gave Fishman a ride, he was on parole after serving time for a rape in Connecticut.

Fishman’s ride lasted only about 15 minutes — Carr dropped him off unharmed — but his memories of that fall 1975 encounter have haunted him for decades.

About six months later, Carr was arrested for an attempted rape of a hitchhiker in the Miami area and then startled detectives when he confessed to kidnapping and raping more than a dozen people and killing four of them. Edna Buchanan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Miami police reporter who wrote a book about Carr, once said: “He was about the most evil person I ever met.”

Fishman was stunned when he saw Carr’s picture on a breaking news alert. He recognized him instantly as the talkative man who’d given him a ride.

In retrospect, Fishman said, he missed several major red flags that day. First, the sedan’s door latch on the passenger side was jammed and Fishman had to roll down the window and open it from the outside. And Carr had casually mentioned he had just got out of prison.

“I’m an intern at a local newspaper. And I’m thinking, ‘Wow, that could be a good story about a guy getting out of prison, trying to reintegrate into the community,” Fishman told CNN. “I really didn’t stop to think or ask him what the crime was. I didn’t have any idea.”

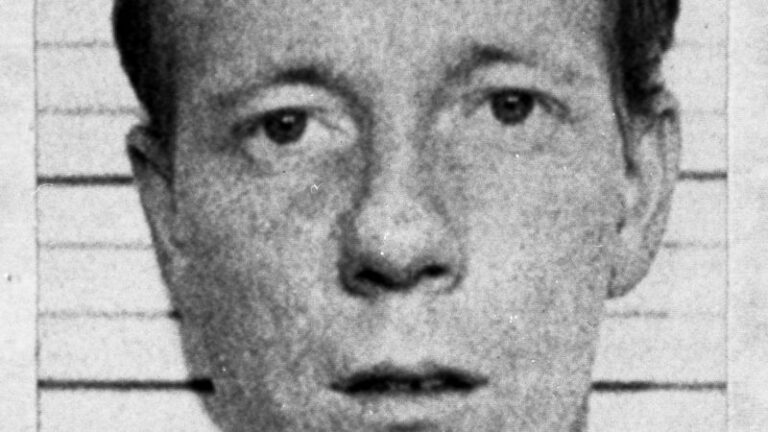

Courtesy Steve Fishman

Carr’s rapes and killings in the 1970s made headlines and stunned the country.

Nearly five decades later, Fishman and Carr’s daughter, Donna, are unraveling lingering questions about the pedophile and killer in a new season of the “Smoke Screen” podcast titled, “My Friend, the Serial Killer.”

In the podcast, they explore Carr’s brutal crimes and and deceptions by digging through confession tapes, a box of his personal items from prison and hours of interviews with detectives.

Although her father died in a Florida prison in 2007, Donna continues to struggle with her family’s dark past. And Fishman still wonders how he made it out of Carr’s sedan alive.

In the 1970s, hitchhiking was considered a safe way to get from point A to B.

“It was a pretty regular mode of transportation back then,” said Fishman, who as an intern constantly relied on random strangers to drive him where he wanted to go.

“Depending on where you lived, we hitchhiked a lot. It was so safe, there were moms who picked me up hitchhiking, with their kids in the backseat with groceries,” he said.

Carr may have played on this belief to carry out his crimes, which mostly targeted hitchhikers.

A TV repairman and car salesman, Carr lived in Norwich with his wife and two kids: Donna and her younger brother. But he traveled nationwide for work and used that opportunity to prey on underage children. Nearly all his crimes, which occurred in the 1970s, involved children under age 18.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Robert Frederick Carr III discusses the murder of a Connecticut woman with a state trooper in July 1976.

In 1972, Carr picked up two 11-year-old hitchhiking friends, raped and strangled them, then buried them in Louisiana and Mississippi. He also picked up a 16-year-old girl and drove her from Miami to Mississippi before he strangled her. He strangled his fourth victim, Rhonda Holloway, 21, not long after his encounter with Fishman and buried her in Connecticut.

Carr would later take investigators on a cross-country trip to show them where he’d buried his victims.

“What he did to those children was truly unprintable,” David Simmons, a detective involved in his arrest, said in a 2007 interview. “In my 33-year career in law enforcement, Carr ranks as the most dangerous child sexual predator-murderer I ever investigated.”

A daughter changes her last name to escape her father’s shadow

Five decades later, Donna is still living in the shadows of her father’s horrific legacy. She is married, with another last name, and asked CNN to withhold her full name for safety reasons.

In an exclusive interview with CNN, Donna tearfully described an adolescence filled with bullying and jokes about having a serial killer dad. She barely looked people in the eye as a child, she said. Those who knew who she was pointed and talked about her father in hushed tones.

Donna said she first learned about her father’s murderous rampage when she was 12. But she didn’t believe he was the monster he was portrayed to be until he led police on a road trip to unearth his buried victims in Louisiana, Mississippi and Connecticut.

“When he agreed to take the detectives on the search for the bodies, the denial could no longer be. Just every range of emotions you could possibly think of for a 12-year-old girl to go through,” said Donna, 60, who now lives in West Virginia. “And that’s when I started to withdraw.”

Courtesy Steve Fishman

Serial killer Robert Carr’s daughter, Donna, in an undated photo he’d kept with him in prison.

Today Donna has a 27-year-old daughter and worries that a public connection to her father could lead to a new wave of harassment for them. She dropped her father’s last name years ago in favor of her married name, and has told her daughter about his history.

“Sometimes in life, his name can come up on things like background checks for employment, and so on,” Donna said. “I raised my daughter to be very mature and to understand things. I didn’t want to lie to her.”

Donna said she wishes people would show more compassion for relatives of convicted killers. They grieve too, but dare not verbalize their loss, she said.

“No one sees what’s happening in the lives of those people just by hearing about a news story,” she said. “They’re humans and they have feelings and they get hurt, and they suffer trauma. And they are very much victims, too, but in a different sense.”

After her father’s crimes became public, Donna spent much of her adolescence holed up inside their Norwich home with her mother. But one day Fishman, still an intern at the newspaper, knocked on their door after her father’s arrest. He pleaded with Donna’s mother to let Carr know that the guy whose life he’d spared months earlier would like to visit him in jail for an interview.

Fishman finally got a chance to interview Carr in prison in the mid-1970s after numerous attempts.

In hours of recorded jailhouse interviews, Carr never pretended to be a saint, Fishman said. He talked about how he stole cars and offered sex to men for money when he was younger. He confessed to killing his victims and sounded not the least bit remorseful, Fishman said.

Courtesy Steve Fishman

Steve Fishman in a recent photo. After Carr’s arrest he interviewed the killer in prison and asked, “Why not me?”

“One of the questions that I had for him was, ‘Why not me?’ And that feels like a really bizarre question to ask. But I did. And he basically shrugged and said, ‘I thought you were too big,’” Fishman said.

Fishman’s paper published his interview with Carr. But as Fishman grew up, got married and became a dad, he started rethinking the tone of his coverage.

“An interview with a serial killer was a big story. It was a big journalism scoop that really kind of sent me on the path to be a journalist. And yet, it was a story that I didn’t really like to think about because I did it when I was 19 and 20, and I was really afraid of what my focus had been,” Fishman said.

Fishman said he believes his friendly conversation with Carr during the ride may have clouded his perspective and humanized the killer a little too much.

“I was really afraid that I had gotten the story wrong, that I somehow didn’t understand or appreciate the horror of the story,” he said. “Back then, I looked at it as a societal problem of how do we treat criminals? How do we rehabilitate rapists? And the utter depravation of it kind of slipped by me.”

That is partly why Fishman is excavating the story in his podcast. He hopes that by understanding Carr better, he can correct the record from a more mature and nuanced viewpoint.

“I’m a father now a few times over. I think about crime and victims differently,” Fishman said. “And that’s kind of why I went to look for Donna.”

After deciding to make the podcast, Fishman sent Donna a Facebook message introducing himself. “She immediately responded with, ‘I’ve been wondering what happened to you,” Fishman said.

Turns out, Donna had spent her lifetime trying to understand her father. She’d wondered: Did he kill people because he was mentally ill and had no access to psychiatric treatment — as Fishman had once written? Or was he just an inherently evil person?

She’d tried reaching out to Fishman over the years and even had called the Norwich paper.

But the decision to be a part of the podcast was not easy.

“I was hesitant, because I really have not spoken much about it. Very few people know that part of my life,” she said. “It took me a little while to make that decision, and then I decided if I was going to do it with anyone, it was going to be Steve.”

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Sheriff Gordon Martin at a shallow grave that held the body of 11-year-old Todd Payton in June 1976 in St. James Parish, Louisiana.

Donna said she believes her father had manipulated Fishman, like he did with everyone in his life. So she and Fishman agreed to meet at her West Virginia farm to understand the complexities of the story from a new point of view.

They looked through boxes stuffed with Carr’s items from prison, including letters Donna had sent him at age 15. “Dear Dad, I love you. I’m sorry I haven’t written in so long,” one said.

Her father responded with letters urging her to find Jesus. He claimed he had found Jesus, too. But he also sent her sexually suggestive letters, leading her to cut off communication with him.

Donna told CNN that she knew her dad was a monster, but she was holding on to the childhood dream of having a nuclear family. In between her flashes of terror and anger, there were happy memories of family camping trips and the Christmas when her father unwrapped a large stereo he’d bought for the family.

Donna said the inappropriate letters from her father finally gave her the strength to severe ties with him. But they were so unnerving that she said she constantly called the prison to make sure he had not been released on parole.

One day in the summer of 2007 she found out he was no longer listed as being in prison and had a brief moment of panic, thinking he’d been set free.

But a call to the prison confirmed that her father had died of prostate cancer. He was 63.

Only after his death did her sense of peace slowly start creeping back.

Donna said that despite her initial reluctance, working on the podcast has been a therapeutic experience that has given her a better sense of who her father was.

“As many diagnoses as my father had as far as his mental state — and there were a lot — I believe he was just born evil,” she said. She’s in counseling and hopes to keep making steps toward healing.

“I kept everything boxed in for so many years. I would just push everything down,” she said. “It was nice to finally talk about it freely.”