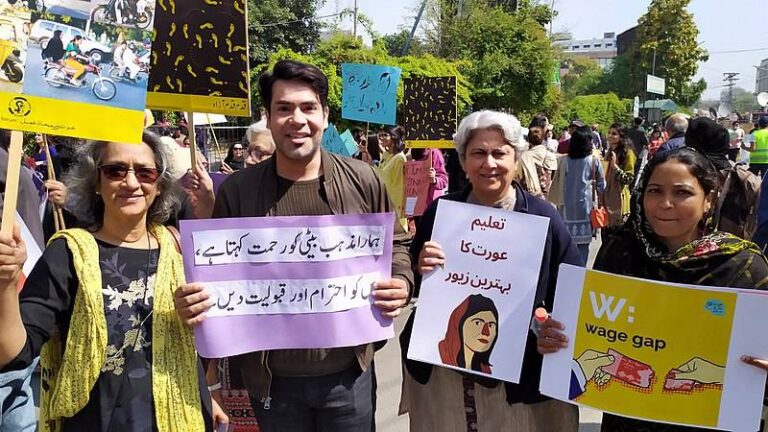

ohOn March 8, 2024, many women in Pakistan participated in demonstrations to show solidarity with International Women’s Day. Conservative religious groups frequently denounce the day as preaching Western ideals. The Aurat March, held in major cities such as Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi, and Faisalabad, sought to raise public awareness of women’s marginalization in the social and political spheres. The demonstrations called for prevention of widespread violence, easy access to healthcare, and economic equity for women, especially in safe working conditions and equal opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing crises, such as gender-based violence, in developing countries such as Pakistan.

During the marches, women typically raise issues such as street harassment, forced labour and lack of representation in parliament. Organisers of this year’s march clarified that the march is dedicated to women’s rights activist Dr Mahlangu Baloch, who is of Baluchi ethnicity. Dr Mahlangu Baloch has been actively protesting against government misconduct such as enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings in Baluchistan. They also expressed concern that with the upcoming general elections scheduled for 2024, only 12 out of 266 members of the National Assembly are actively participating in parliamentary activities.

The Aurat March (Women’s March), a series of protests in Pakistan, has faced legal obstacles and controversy after digitally altered images of women holding signs attracted widespread attention. In 2020, women who participated in the marches were targeted by Islamic extremists. At the same time, conservative religious groups organized modesty rallies in Lahore and Karachi, calling for the upholding of Islamic principles. The marches have been criticized for promoting class and Western ideals in Muslim countries and for disrespecting cultural and religious sensitivities.

On September 9, 2020, a sexual assault case occurred near Lahore, Pakistan, in which a woman was the victim. The incident sparked a debate on Pakistan’s criminal justice system and the root causes of sexual violence. To address the issue, feminists from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, Awami National Party, and feminist groups organized the Islamabad Women’s Freedom March. The increase in sexual violence cases in the country was attributed to victim blaming, flaws in the criminal justice system, and inadequate education curricula. Media and civil society debated the issue.

In Pakistan, Islamists say sexual assault is the result of “behayai,” or “immorality.” The rise in coeducation has led to an increase in sexual assaults against women, girls, and boys. According to their belief, when boys and girls study together in school, it increases the chances of developing extramarital relationships, which is forbidden in Islam. In response to this issue, Islamists have called on the Pakistani government to legalize public executions of rapists under the Islamic penal code, which prescribes public execution as a beheading. The road attack incident sparked a widespread debate about violence that specifically targets individuals on the basis of their gender. In December, the government enacted a new law against rape, promising speedier legal procedures and tougher penalties. However, the country’s response to violence against women has failed to address underlying factors and should focus on prevention. In addition, there is a demand for policies such as national hotlines, shelters, legal aid, and psychosocial support.

Women are vulnerable to violence because of their economic dependence on family members, including fathers, brothers, and spouses. Women are expected to manage household chores and are discouraged from taking up employment outside the home due to poor working conditions and public spaces. The shadow economy is largely made up of women working for low wages and is vulnerable to external economic forces. The dominance of men in controlling household finances and assets, combined with the expectation that women should tolerate violence to protect their families, exacerbates these gender gaps. Pakistan’s patriarchal norms maintain these gender role disparities, resulting in the establishment of systematic hostility towards women in both political and governmental spheres. Although there are laws banning child marriage, workplace harassment, domestic violence, “honour” killings, and acid attacks against women, these laws are often not enforced.

According to the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Report, Pakistan ranks 153rd out of 156 countries. Only Afghanistan, Yemen and Iraq rank worse. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, 47% of married women have suffered sexual assault, including rape, and 90% have experienced domestic violence from a spouse or family member. The Thomson Reuters Foundation ranks Pakistan as the sixth most dangerous country in the world for women. Women make up just 22% of the (paid) labor force and 18% of national labor income.

In Pakistan, Muslim individuals, primarily male and female, have organized “haya” (or “morality”) marches to protest against feminist actions, which they see as promoting immorality in the Muslim-majority country. They promote policies that increase women’s participation in public life, such as improved access to higher education and economic opportunities, freedom to choose a spouse, and equal rights to inherit land. Islamists advocate for restricting women’s participation in public life and religious commitment. They believe that sexual violence is a result of the presence of both genders in the public sphere, and they have intellectual support from government institutions. They promote the implementation of Islamic law in all aspects of society. Islamists create discriminatory materials, particularly targeting feminists, and urging government institutions to hold victims of sexual assault accountable. Additionally, they use physical force against supporters of feminist causes.

Pakistani feminists are challenging Islamic pretensions of women’s rights and empowerment through protests, marches, speeches and sit-ins. They use rhetoric like “my body, my choice,” “mera jism meri marj” and “hak mehal (bride gift)” to challenge the assumption that the small amount of cash given to women as a divorce settlement does not constitute divorce compensation. Their goal is to change public perception and oppose the practices of dowry and murder.

During the dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s, women’s civil rights were restricted and the government used religious politicians to consolidate its power. The pioneering feminist movement, the Women’s Action Forum, rose to power during this upheaval by repealing the Hudood Ordinances, which discriminated against non-Muslim women who testified in rape and gang-rape cases. A demonstration calling for women’s awareness and basic rights was held on Mall Road in Lahore, where tear gas was used to disperse and arrest protesters. The Women’s Action Forum has consistently campaigned for justice, particularly for minorities and women. In 2006, the law was amended to remove the requirement of four witnesses, reflecting the organization’s commitment to addressing injustice against minorities and women.

With the slogan “No Sexual Harassment at Workplace”, the Alliance Against Sexual Harassment (AASHA) became the second most prominent feminist movement in Pakistan in 2000. Bushra Khaliq, a member of the Global Women’s March, and activist Fozia Saeed reached out to key stakeholders including political parties, lawmakers, media and grassroots women. Their efforts were fortunate enough to result in the passage of a law in 2010 to protect women from workplace harassment.

In 2015, Pakistan’s parliament passed 20 ordinances and provincial assemblies enacted 120 laws, with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa having the most laws. The 18th constitutional amendment expanded provincial statutory powers, and provinces continued to exercise their powers to enact significant legislation. Islamic doctrine permeates the police, courts, media, politics, education, and academia, leading to discrimination against women. Sexual assault is sometimes portrayed as a public nuisance rather than a criminal act, but the laws against it are strong and carry severe penalties.

Authorities try to blame the victims in cases of sexual assault, claiming that they converted to Islam because they loved their perpetrators. This allows perpetrators to easily evade criminal laws. The conviction rate for sexual violence cases is 2.5%. A weak judicial system and political discourse condones and encourages sexual violence against vulnerable groups, including children, women from low-income families, religious minorities, and transgender people. The Aurat March has been planned since 2018 to bring together people from disadvantaged groups, but it has only been held in a few cities and has not gained support in rural areas.

Pakistan’s mainstream media has harshly condemned the movement, religious pundits, political establishment and the public, and the criticism has been intensified by retaliation by the Taliban and other groups. Last year, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Provincial Assembly formally condemned the Aurat March, and parliamentarians filed protests.

Critics of the Aurat March argue that Islam and feminism are incompatible concepts based on a patriarchal cultural perspective. Thus, individuals who denounce patriarchy are accused of being irreligious. As religion is integral to Pakistani identity, such claims are difficult to dismiss. Women’s rights groups like the Aurat March must incorporate feminism, modernity, and Islam into their arguments, as well as progressive religious scholars, to avoid division, misunderstanding, and failure. Failure to maintain a spiritual connection could undermine the Aurat March’s ability to build a critical mass for gender justice in Pakistan.

Pakistani women launched the Aurat March movement to mark International Women’s Day, raise awareness about the situation of women, and reclaim their rights in the public and private spheres. The program engages the youth, encourages inclusion, and advocates for the downfall of patriarchal structures and social change. The posters, which are outspoken, humorous, sarcastic, and loud, have sparked controversy and debate both online and offline. Critics allege that the Aurat March is an elite-class movement with immoral demands and Western goals. They argue that social media hype, a patriarchal social system, and the extreme views of opinion leaders have all led to the criticism. However, the Aurat March does not portray the feminist movement in Pakistan in a negative light. It is a day to celebrate femininity, community, and self-discovery, whether transgender or feminine. It aims to teach women of all ages that it is acceptable to ask for respect from their families, and that women have a voice.

[Representational image by Nawab Afridi, via Wikimedia Commons]

Wafa Hussein is a PhD student in Political Science at the International Islamic University of Indonesia. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.