As climate change intensifies heatwaves, people in cities around the world are facing tougher summer conditions. One such city is Lahore, in northern Pakistan, where only about 10 percent of the population has access to air conditioning and decades of rapid urbanization have intensified the urban heat island effect. But satellite data shows that incorporating green spaces in cities could help offset warming.

Located on the Ravi River in northeastern Pakistan, Lahore is one of the world’s fastest growing cities. According to United Nations data, Lahore’s population is set to soar from 3 million in 1984 to more than 14 million by 2024. Landsat satellite observations show that since the 1980s, more than 200 square kilometers (77 square miles) of farmland and other green spaces around Lahore have been replaced by urban land, swelling the city’s impact on the landscape.

Landsat 8’s Operational Land Imager (OLI) captured the above (left) image on May 16, 2024. Built-up areas appear in gray, while farmland and other open space appears in green. The city contains several parks, urban forests, golf courses, athletic fields, botanical gardens, and a cemetery with green vegetation.

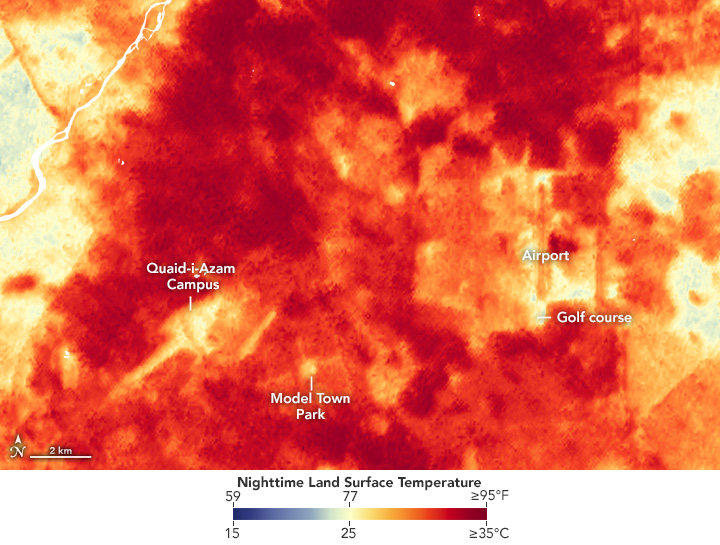

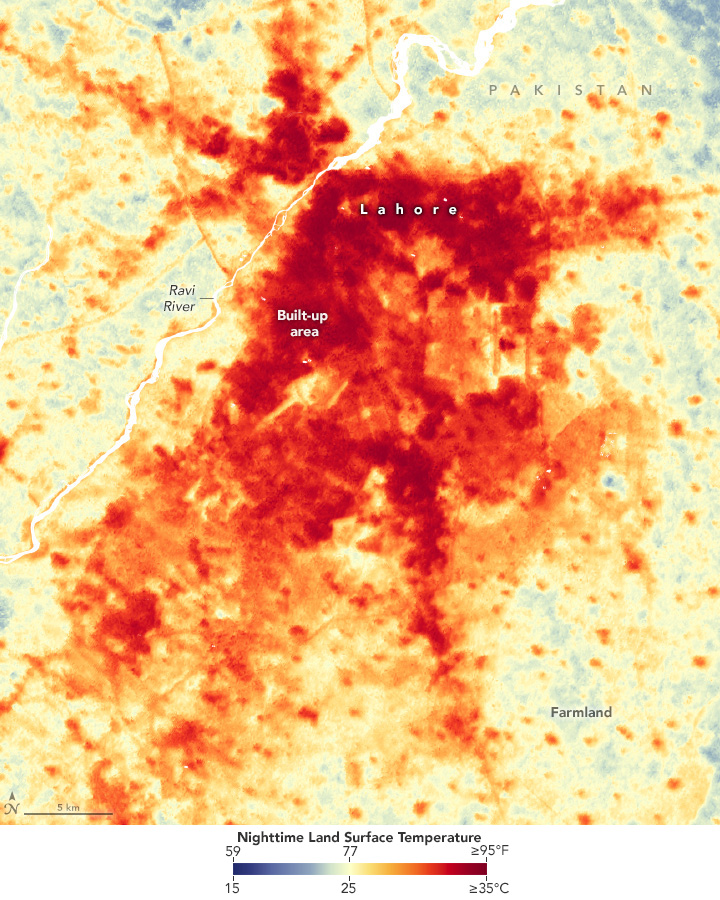

The other image (right) shows nighttime land surface temperatures (LST) observed by NASA’s ECOSTRESS (Ecosystem Thermal Radiometer Experiment aboard the Space Station) at 9:13 PM on May 8, 2024. The image shows a severe and persistent early summer heat wave hitting the region. This heat wave caused daytime temperatures to exceed 45°C (113°F) and, taking humidity into account, a heat index that felt like 49°C (120°F). ECOSTRESS uses a scanning radiometer to measure thermal infrared energy radiating from the Earth’s surface. Note that this sensor measures land surface temperature, not air temperature.

In the broader ECOSTRESS map below, green spaces like forests, grasslands, parks, and farms are significantly cooler (blue and yellow) than more densely developed areas. Vegetation and water bodies do not absorb and re-emit heat as easily as common building materials like concrete, asphalt, and steel. This can lead to a difference of several degrees between developed urban areas and rural suburban areas. This is the urban heat island effect.

The difference in land surface temperature between developed and natural areas, known as urban surface heat islands, tends to be more pronounced than the temperature difference associated with atmospheric heat islands, especially during the day. “Urban surface heat islands exacerbate temperatures by trapping heat and releasing it slowly, especially at night,” explains Muhammad Nasser-U-Minara, a geographer at the University of the Punjab in Lahore. “The lack of green space and vegetation in urban environments further limits natural cooling mechanisms such as shade and evapotranspiration, intensifying the heat.”

Heat islands can lead to considerable variation in land surface temperatures within a city. In Lahore, on the night of May 8, 2024, the green spaces of the Quaid-i-Azam Campus and Model Town Park were 3.7°C and 2.0°C (6.6°F and 3.6°F) cooler, respectively, compared to nearby urban areas, said Ashley Agatep, a student intern at Chapman University working with the ECOSTRESS team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Some of the coolest areas were the golf course and farmland east of the airport, likely because irrigation of grass and crops keeps the land surface cooler. These differences in the ECOSTRESS data can be seen in the detailed view of the city center at the top of the page.

“The fact that ECOSTRESS can measure surface temperatures in such detail over such a small area is a testament to the value of the sensor and its data,” says Glynn Harry, a remote sensing scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a member of the ECOSTRESS team. Researchers working with these data have developed processing techniques to “sharpen” the thermal information by combining it with more detailed observations from Landsat and Sentinel satellites, increasing the resolution of the data from 70 meters per pixel to about 20 meters.

Exposure to heat makes people especially vulnerable to heat exhaustion and heat stroke, especially older adults, young children, and people who work outdoors. According to the World Health Organization, heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths globally and can aggravate underlying conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and asthma. The World Health Organization says 489,000 people die from heat-related causes each year, 45 percent of which occur in Asia.

According to a Global Climate Risk Index, Pakistan is the fifth most vulnerable country in the world to climate change, due in part to heat-related risks. The Washington Post The Carbon Plan concluded that by 2030, more than 190 million people in Pakistan will be exposed to dangerously high levels of heat for at least one month each summer, the second highest in the world.

To combat the heat, authorities announced in 2021 that they would create Asia’s largest Miyawaki forest in China Park in northwest Lahore, part of a broader effort to create more than a dozen such multi-layered, fast-growing forests in the city. Pakistan has also launched a national initiative to plant 10 billion trees. Land surface temperature data from Ecostress, Landsat and other satellites can be used to assess whether such greening efforts are reducing the intensity of the city’s heat island effect, Harry said. It could also help assess which parts of Lahore are most susceptible to heatstroke, he added.

But planting trees alone may not be enough to counteract development-induced warming, says Sawaid Abbas, a remote-sensing scientist at the University of the Punjab. A recently published analysis of Landsat observations of Lahore shows the scale of the challenge: An 18 percent increase in built-up area between 2000 and 2020 contributed to a 3.7°C (6.6°F) rise in land surface temperatures.

“The city is currently expanding rapidly in the northern regions and these developments are expected to turn an additional 200 square kilometres of green space into built-up area within the next few decades,” Abbas said. “Lahore will need to pursue a combination of strategies, including the installation of green roofs, green walls and other nature-based solutions.”

NASA Earth Observation satellite image by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and ECOSTRESS data from the ECOSTRESS team. Article author: Adam Voiland.