Religion is all-encompassing in Pakistan. This is hardly surprising for the only country in the world founded in the name of religion. Every institution, from the military, civilian politicians, judiciary, bureaucracy and the once glamorous cricketers, tries to outdo the others in faux piety and toxic puritanism. Many attribute the decline in religiosity to the late military dictator General Ziaul Haq and the era of Islamism he created, but many since have been equally complicit in turning the country into a hotbed of extremism.

Pakistan’s enduring curse is the persistent and mistaken belief of its leaders that they can somehow harness religion to their own advantage without succumbing to its inevitable harmful consequences. The country’s founding father, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, was the first to believe in this failed logic of running with the hare and hunting with the hounds. Today’s regressive Pakistan bears no resemblance to the one envisioned by Jinnah in his “secular” speech to the Constituent Assembly in 1947, a recording of which was conveniently “lost” and its spirit buried for posterity. Even the relatively modern and secular “establishment” of Pakistan – the army – is now “Imam, Taqwa, Jihad fi Sabilillah(Faith, Piety and Holy War in the Path of Allah)! Fittingly, General Asim Muneer is the first Pakistan Army Chief to become “Hafiz Quran” (someone who has memorised the Quran).

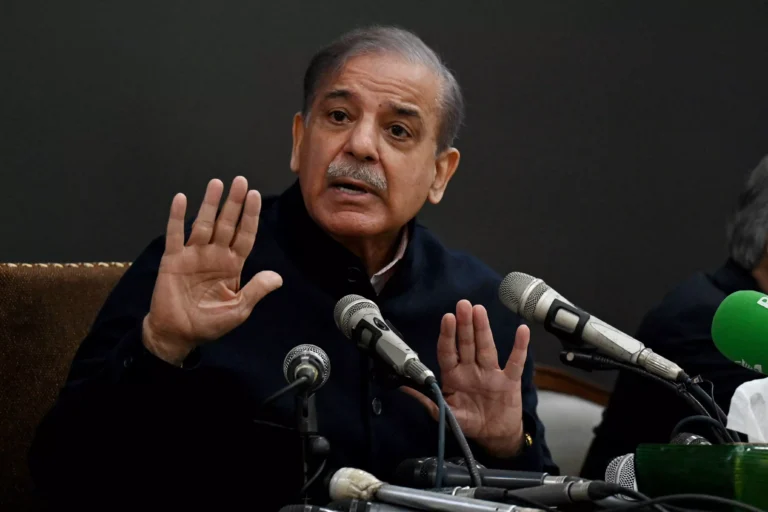

Civilian politicians too often have to pay for inciting religiosity, and so-called secularists like the Bhutto family have blood on their hands for initiating constitutional discrimination against the Ahmadiyas in 1974 and founding the Taliban (by PPP interior minister Nasirulla Babar). Later Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was hanged by the even more bigoted Zia-ul-Haq and Benazir was assassinated by extremists. Nawaz Sharif was General Zia’s hand-picked man and the PML(N) led by the Sharif family ended up making many alliances with many religious parties and clerics. Even former playboy and cricketer Imran Khan, who portrayed Riyasat-e-Madinah as a utopia, later became infamous under the moniker Taliban Khan. As the situation in Pakistan became more dire and desperate, Pakistani society became more intolerant, radical and violent.

The export of religious fundamentalism became an industry (especially in the 1980s and 1990s) and India became an obvious market. Hillary Clinton’s wise warning that “the snake in your backyard doesn’t just bite your neighbor” was ignored until the inevitable happened. Pakistan’s own actions created a Frankenstein’s monster, and the genie of extremism, once unleashed, refused to be put back in the bottle, and terrorism was the inevitable result. And once on autopilot mode, terrorism could not be controlled and soon turned on its parent, the state of Pakistan.

Ironically, the founder of the Taliban is now facing an existential threat from its metastasized organization, the Pakistani Taliban Movement (TTP), one of many independent targets. Over the past two decades, more than 80,000 Pakistanis have been killed by militants from across the Durand Line, far more than the number killed in combat with India. The past 18 months have been particularly devastating, with over 700 terrorist attacks recorded last year alone. This is despite various military operations such as Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad, Operation Khyber, Operation Zarb-e-Azb, and Operation Raha-e-Shahadat, all of which were highly militarized. Yet terrorism thrived.

Finally, a belated but crucial recognition of the nexus between terrorism and potential religious extremism evolved with the conceptualization of Operation Azm-e-Inteqam (Resolved for Stability) as a “multi-sectoral, multi-agency, system-wide national vision for the enduring stability of Pakistan.” There seems to be a recognition that, as always elsewhere in the world, one cannot pander to unchecked religiosity and expect it not to run wild. The crucial difference between numerous previous military operations and Operation Azm-e-Inteqam seems to be the inclusive and expanded “scope” of the operation, which is said to include socio-economic and political imperatives in addition to military operations.

It is too early to speculate on its operational effectiveness, as it depends on the underlying intent, sincerity and integrity of whether the various levers of Pakistan’s leadership – military, politicians, judiciary and even clergy – can purify themselves from instincts institutionalised by decades of religious impulses. This demands a complete U-turn in the narrative on sovereignty. Given that many centres of power within Pakistan are legitimised by religion, it is overly optimistic to expect a complete and uniform withdrawal of religion. Many see the soundness of this course correction as a “whitewash” to convince countries like China, multilateral organisations and even the United Arab Emirates, who are very wary of extending further aid for Pakistan’s bailout without a substantial course correction.

But simply embracing the task of deradicalizing society (as important as military operations) is itself a radical break with the past. Religious extremism is the oxygen that terrorism needs to survive. The moment the state suppresses the relevance of religion (beyond private matters) in the social/governance sphere, it can break free from the shackles of the historical past that has inflamed and imploded Pakistan from within. Curiously, the instability of the coalition government’s public credibility and the unprecedented violence against Pakistani military personnel bode well for generating joint efforts to get out of this extremist mess. But Pakistan has traditionally remained incorrigible in some respects, especially with regard to religion, and therefore one must be realistic (but hopeful) about the success of the “Azmi-Intekam.” At the very least, that is a positive recognition.