Thirty years ago, Chinese dissidents were being smuggled out of the country in a secret operation called Yellow Bird, and one of them told the BBC that the Chinese government is still tracking them. There is.

June 1992: In the middle of the night in the South China Sea, a Chinese patrol boat approaches a boat en route from the communist mainland to Hong Kong, then a British colony.

When Border Patrol came on board to talk to the crew, their voices could be heard by a group of people packed into a secret room below deck.

These secret passengers had been given emergency orders when the patrol boat was spotted minutes earlier.

“We were told to hide,” said one of them, Yang Xiong. “Please don’t make a noise!”

Most of those hiding were economic immigrants hoping to find work in Hong Kong, but Yang was not.

He is a political dissident and would be in trouble if discovered.

Yang had been smuggled out of China as part of a covert operation codenamed “Yellow Bird.”

Eventually, the patrol departed, and in the early morning, Mr. Yang arrived in Hong Kong, although he had never been on a ship before that night.

After a hearty breakfast, he was taken to the detention center. This was for his own safety, he was told. Walking around town can be dangerous.

Gordon Colella examines the growing tensions between China and the West.

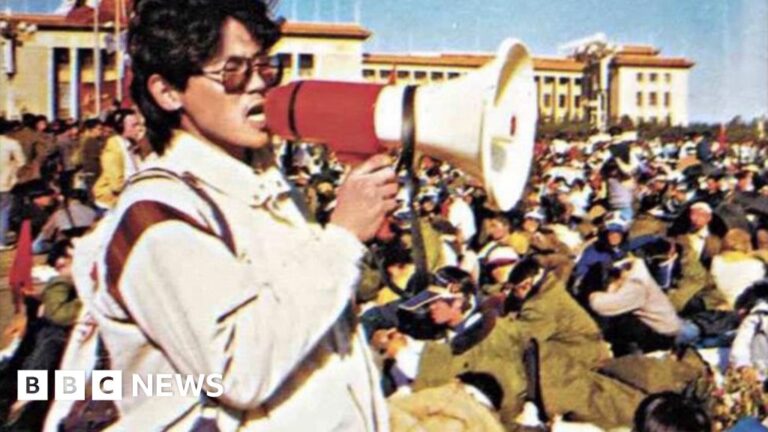

Being detained was nothing new for Yang. He had already spent 19 months in a Chinese prison for his involvement in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. The students were calling for greater democracy and freedom, but the Communist Party sent in tanks to suppress them.

In late June 1989, the Chinese government announced that 200 civilians and dozens of security personnel had been killed. Other estimates range from hundreds to thousands.

Once released, Yang heads to southern China where, in a scene straight out of a spy movie, he is sent from one phone booth to another trying to contact people who can free him. Ta. .

He was not the only dissident to embark on this perilous journey.

In an interview with the BBC for the new series Shadow War: China and the West, Chaohua Wang reflected on his escape.

Although she was number 14 on the list of 21 most wanted people after the Tiananmen massacre, she managed to evade arrest and hid in a small room for several months before heading south to become part of the Yellow Bird escape line.

“I was like a package that was moved from one place to another.” [person] to another person,” she says.

“I didn’t even know the name Yellow Bird for years.”

Yellowbird may sound like classic espionage, but many believed that the intelligence agencies (MI6 or CIA) came up with the idea. But they weren’t.

In fact, this was a private undertaking undertaken by a group of concerned citizens in Hong Kong, motivated by a desire to help those on the run. This included the local film and entertainment industries, and (more conveniently) organized crime in the form of triads.

“They are [the triads] They had a lot of Chinese police in their pockets,” says Nigel Inkster, an intelligence officer based in Hong Kong at the time. This made it possible to move people from hiding places in Beijing and smuggle them across the border.

Britain and the United States only became involved when people arriving in Hong Kong needed to figure out where to go next.

Mr. Yang remembers being visited by someone he called an “English gentleman” who helped him with the paperwork, although he declined to give his name.

“You should go to America instead of England,” the man told him. Within days, Yang arrived in Los Angeles. Chaohua Wang also ended up in the United States.

Former officials told the BBC that Britain was reluctant to host Tiananmen protesters because it was desperate to avoid upsetting China in the run-up to Hong Kong’s 1997 handover.

Britain had signed the agreement in 1984, but the Tiananmen incident five years later raised difficult questions about Hong Kong’s future.

image source, Getty Images

In 1992, a few weeks after Mr Yang arrived in the colony, former Conservative cabinet minister Chris Patten became Hong Kong’s last governor.

He said he was determined to embed greater democracy in the hope that it would survive the handover, and that he is committed to democratic reforms to Hong Kong’s system aimed at broadening the voting base in elections. The proposal was announced.

This reform was opposed not only by the Chinese leadership but also by people in London who did not want to antagonize the Chinese government.

“My main responsibility was to give the people of Hong Kong the best chance of continuing to live in freedom and prosperity, and to do so in 1997 and beyond,” says former governor and current Lord Patten. He also knew about Yellow Bird, but said he was not involved.

The reluctance to allow dissidents to visit Britain, and the anger in some circles over Patten’s reforms, speaks to a central issue of the 1990s that is still relevant today: the West avoided China’s wrath; In particular, how far should we go to respond to the rise of China? What about values like human rights and democracy?

Yellowbird ended on a rainy night in July 1997, when Hong Kong became Chinese sovereign. For several years Patten retained the freedom he had sought to secure. But over the past decade, China under Xi Jinping has taken a more authoritarian turn and sought to bring Hong Kong into line.

image source, Getty Images

Jan obtained American citizenship and lived an exemplary American life. He joined the U.S. Army and served in Iraq as a chaplain.

He may have thought his new home was beyond the reach of the Chinese Communist Party, but he was wrong.

He has decided to run for public office in 2021. He ran in the Democratic primary for New York’s 1st Congressional District.

During the campaign, Yang began noticing some strange occurrences. An unknown car followed him and lurked outside the house where he was staying at 3am. People would try to prevent him from speaking at campaign events.

When the FBI came to talk to him, he found out why. A U.S. private investigator said he was asked to monitor Yang by someone in China. It seems that the idea of a former Tiananmen Square participant entering the US Congress was not accepted.

“He specifically told our private investigator that he needed to undermine the victim’s candidacy,” says FBI agent Jason Moritz.

The FBI was able to monitor the situation because a person based in China suggested that investigators dig up dirt on Yang. If nothing was found, they were instructed to make something. If that didn’t work, it was suggested to hit him or even cause a car accident.

“They are trying to stifle and kill my campaign,” Yang explains.

The person who directed the private investigator evaluated by the FBI was working on behalf of China’s Ministry of State Security. They were charged but could not be arrested because they were outside the United States.

China has consistently denied allegations of political interference. But it is not the only country said to have become aggressive in pursuing people it considers dissidents in other countries. There are also claims that there are “overseas police” in the UK and US and that individuals are being pressured to return to China or remain silent.

Yang’s story makes clear that as China becomes more confident and assertive at home, it is also seeking to expand its reach abroad. And that has led to increasing friction over issues of espionage, surveillance and human rights.

Meanwhile, Yang’s message to Western governments when dealing with China is simple: “They have to be careful.”

‘Shadow War: China and the West’ begins on Monday 13 May at 13:45 on BBC Radio 4 and can also be heard on: bbc sound