Enter H-20.

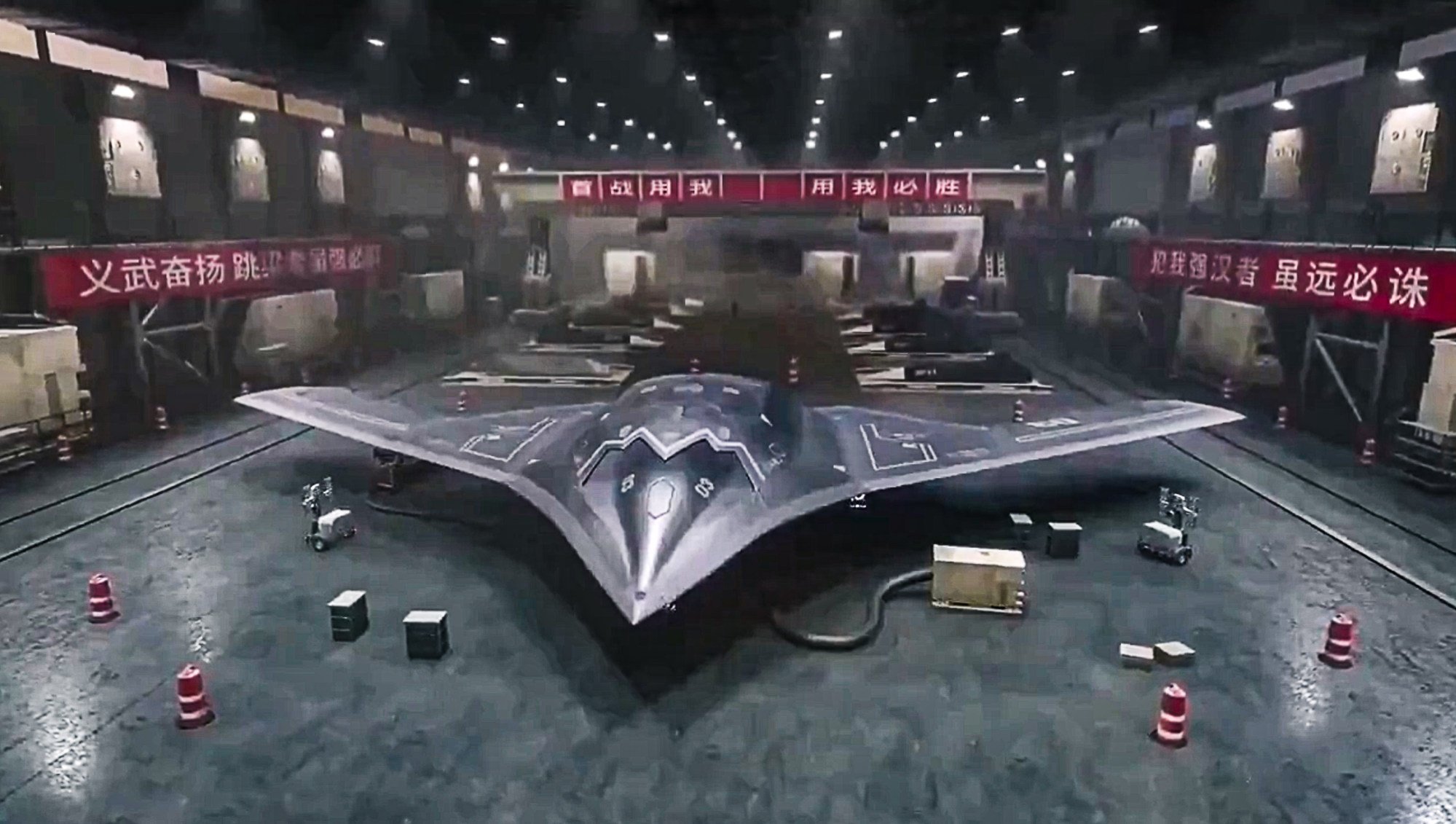

Propaganda videos produced by the People’s Liberation Army Air Force over the years have suggested that the Chinese bomber would feature a stealthy flying wing design and low-observable coatings, like the American B-2.

The H-20’s specifications are unknown, but the Pentagon’s 2021 annual report to Congress said the aircraft would likely have a range of at least 8,500 kilometers (5,280 miles), a payload of at least 10 tons and the ability to carry conventional and nuclear weapons. It could also be equipped with Chinese hypersonic weapons, the report said.

This range would allow for an intercontinental strike radius — for China, that could mean a second Pacific island chain like Guam, or even further out to Hawaii, or the U.S. West Coast with aerial refueling — elevating an air force focused on homeland defense into a global offensive power.

The aim is thought to be to give it capabilities similar to fifth-generation fighter jets, such as stealth, hyper-maneuverability, super-situational awareness and potentially the ability to cruise at supersonic speeds, allowing it to penetrate enemy defenses undetected and become nearly unstoppable.

“[The H-20] “This is a major upgrade, a new generation of new aircraft,” PLA Air Force Vice Commander Wang Wei said at China’s “Two Sessions” political gathering in March.

“A new generation of equipment will bring a new generation of fighting power. That’s something to be proud of and excited about.”

The final jigsaw puzzle of the nuclear trinity

Land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and sea-based ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), along with strategic bombers capable of delivering nuclear warheads, complete the so-called “nuclear triad,” a complete nuclear deterrent once possessed only by the superpowers of the United States and Russia during the Cold War.

In the event of a nuclear attack, it would be difficult for an attacker to simultaneously neutralize all of a country’s nuclear capabilities with a variety of deployment and delivery platforms, allowing that country to credibly maintain the threat of retaliation.

Long-range strategic bombers are the most difficult of the three to maintain and operate, but are essentially strike aircraft intended to primarily target other nuclear powers thousands of kilometers away as part of a nation’s strategic deterrent, though they can also be used to intimidate nearby adversaries.

The advantage of air-based nuclear weapons, or strategic bombers, is that they offer both flexibility and a clear signal of deterrence, said Zhao Tong, a senior fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Beijing-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“Unlike missiles, which cannot be withdrawn once launched, strategic bombers have a degree of flexibility. They can be launched at an enemy in a crisis and withdrawn as the situation changes,” he said.

Meanwhile, the presence of bombers on the runway or taking off could be easily detected by enemy satellites and could be used to convey a clear and effective deterrent intent.

“Routine flights such as patrols over the Western Pacific do not necessarily indicate an imminent attack, but they do serve to convey a readiness and willingness to use force if necessary,” Zhao said.

He said the bombers were better able to survive once airborne than silo-based ICBMs and were harder to target or destroy, especially within domestic airspace and far from hostile territory.

For China, which is committed to a “no first use” principle of nuclear weapons, it was particularly important to ensure that its nuclear arsenal could withstand a first attack and retaliate with a second strike.

However, strategic bombers are perhaps the weakest weapon in China’s triad, and despite being the only country other than the United States and Russia that possesses them, the H-6 is the least developed of the strategic bombers in service in the world.

The end of the never-ending H-6?

One of the Soviet Union’s earliest jet bombers, the twin-engine Tupolev Tu-16, was introduced to China under a production license in the 1950s and was subsequently built as the H-6 by Xi’an Aircraft Industrial Corporation. It conducted China’s first airborne nuclear weapons test in 1965, and has since conducted at least a dozen more.

Over the next few decades, more than 20 variants have been developed for a wide range of roles from aerial refueling to electronic warfare, with upgrades and construction continuing into the 2020s, and the PLA Air Force is estimated to still operate more than 230 H-6 family aircraft.

The latest nuclear-capable bomber variant, the H-6N, has a subsonic range of 6,000 km, can carry a 15-ton payload and is armed with stand-off cruise missiles.

By comparison, Russia’s Tu-160 strategic bomber flies at more than twice the speed of sound and can carry a 40-ton payload, the American B-2 is ultra-stealthy, and even the American B-52, another 1950s aircraft, can carry up to 32 tons of ordnance.

As part of the nuclear deterrent threatening the United States, the H-6N’s attack range could theoretically cover Hawaii and, with aerial refueling, parts of the west coast of North America.

But in reality, the decades-old platform is so easily detected and vulnerable to modern air defense systems that it would be unable to travel long distances without being intercepted, according to Chinese military journal Weapon Industry Science and Technology.

“The H-6N’s penetration capabilities are very limited, and therefore its effective nuclear deterrent power is also very limited,” the analysis said, adding that the H-20’s flying wing design and low-observable coatings give it stronger penetration capabilities.

“Equipped with nuclear missiles, the H-20 will provide a more realistic and powerful nuclear deterrent… The H-20 will mark a strategic breakthrough for China and significantly expand its strategic space.”

The struggles of large aircraft

Since the early 1970s, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force had been seeking to develop a “long-range strategic bomber” capable of carrying seven tons of ordnance and flying 11,000 kilometers, but the project never got underway.

Around the same time, proposals were made for a large military transport plane, the Y-9, and a large passenger plane, the Y-10. The Y-9 was cancelled after two years, and the Y-10 completed a few test flights but was cancelled in 1986 due to budgetary constraints.

The failure of the “big three” – the Y-9 transport plane, the Y-10 passenger plane, and the PLA Air Force’s unnamed “long-range strategic bomber” – was seen as a major blow to China’s aviation industry. These projects were only revived in 2007.

There was even speculation that the Water project might be canceled, given the growing importance of drones on the modern battlefield and the slow pace of their development compared to the PLA’s urgent needs.

But Chinese military commentator Song Zhongping said this was unlikely.

“With their long operational range, super-penetration capabilities and large loads of destructive ground attack weapons, stealth strategic bombers play an irreplaceable role that cannot be matched by any other asset,” he said.

Jin Canrong, a professor of international relations at Renmin University of China in Beijing, said the delay is likely due to the U.S. Air Force’s unveiling last year of the B-21 Raider, a smaller and much cheaper strategic bomber with more advanced avionics for situational awareness than the 35-year-old B-2. The B-21 is due to enter service by 2027.

Jin said strategic bombers are very expensive equipment and therefore must be state-of-the-art.

“So I think the H-20 is now being tailored to B-21 specifications rather than the B-2.”

The PLA is urging caution in this space.

The most recent official source to speak about the H-20 was PLA Air Force Vice Commander Wang Wei, who said in March that an official announcement about the H-20 would be made “soon.”

“There are no technical problems. Our researchers are doing their job well and are very competent,” Wang said.

In its June issue, the magazine Ordnance Industry Science and Technology analyzed the technical aspects of the stealth bomber, suggesting that all major hurdles in the PLA’s previous projects have either been resolved or are on track.

The flying wing’s aerodynamic design has been tested on drones such as the GJ-11, which was unveiled in 2019, and its radar-absorbent coating has been applied to the operational J-20 stealth fighter. The magazine said the rapid success of the Y-20 project proves that complex, large-scale military aircraft development projects of this scale are achievable.

The domestic production of powerful aircraft engines, a long-standing challenge for Chinese aircraft, is also showing signs of overcoming technical bottlenecks, with plans to equip the C-919 with domestically produced CJ-1000 engines and the Y-20 with WS-20 engines, the magazine reported.

“Through the development of new generation aircraft such as the J-20 and Y-20, China’s aviation industry has grown by leaps and bounds and accumulated sufficient experience with large and advanced aircraft. Indeed, no significant technical problems remain,” the report concluded.