According to media reports, Chinese social media platforms have shut down extreme nationalistic posts inciting hatred towards Japan after a Japanese mother and child were injured in a stabbing attack at a school bus stop in Suzhou, west of Shanghai, on June 24.

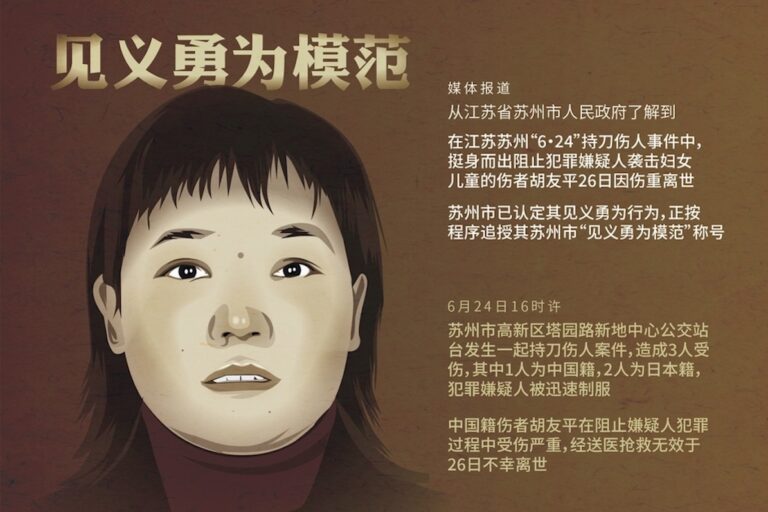

According to reports, a female bus attendant who tried to protect the Japanese passengers was killed in the melee.

The attacker was an unemployed Chinese man in his 50s whose personal hardships appeared to have made him susceptible to ultra-nationalist online “influencers” who specialize in stoking hostility toward Japanese and Americans to attract followers and generate revenue.

The incident marks the second high-profile knife attack against foreigners living in China in a month after four American university lecturers were stabbed in a park in the northeastern Chinese city of Jilin on June 10.

China has reportedly seen several knife attacks recently, mostly targeting fellow Chinese, and knives are more commonly used in violence than guns because, unlike Americans, ordinary Chinese people do not have easy access to guns.

One American long-time resident of China told the Asia Times that the spike in knife attacks may be due to the stress of falling income and other economic hardships that are driving many Chinese men to despair.

There has been an outpouring of sympathy for the Suzhou victims and praise for the bus driver, Hu Youping, who has been hailed as a heroine in both China and Japan, but there has also been hostility and sarcastic comments on Chinese social media.

Wang Xichen, a veteran founder and editor of China’s state-run news agency Xinhua, wrote on the Pekingnology Substack:

Recently, several users [of social media] “They used certain events to post inappropriate comments with distorted, exaggerated, and fabricated content, inciting extreme nationalistic sentiment. Examples include promoting the “eradication of anti-Japanese traitors,” calling for the creation of a “modern Boxer Rebellion,” spreading slanderous claims that a school bus driver who died while rescuing people in Suzhou was a “Japanese spy,” and fabricating extreme populist statements such as “it would be best if the whole of Japan sank, leading to early ethnic extermination.”

In response to such extreme comments, Chinese social media operators such as Douyin, NetEase, Tencent and Weibo have stepped up their crackdown.

Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, said “these comments disrupted the platform’s positive and peaceful atmosphere and incited illegal activities.” NetEase issued a statement asking users to report inappropriate and harmful expressions that express extreme nationalistic sentiments or incite Sino-Japanese conflict. Tencent has reportedly processed more than 800 violations of its social media platform’s rules.

China’s mouthpiece media also made their position clear, with the state-run People’s Daily writing: “We also do not accept ‘xenophobia’ or incitement to hate speech… This is unacceptable…”

Hu Xijin, a former editor-in-chief of the Communist Party-run Global Times and a prominent commentator, said China must “avoid over-exaggerating external challenges and hostility online, turning extreme nationalism into a commodity for hating the United States and Japan, and blaming most of China’s problems on external factors.”

A Japanese trade delegation led by veteran Japanese politician Yohei Kono met with Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng in Beijing on July 1 to raise the issue of extremism. According to Japanese media reports, Kono asked whether the attackers were specifically targeting Japanese people, to which the vice premier replied that they were not.

The Chinese government’s official line is that both the stabbings in Suzhou and Jilin were “isolated” incidents.

Japan’s Asahi Shimbun newspaper reported that “Following the knife attack in Suzhou and a series of recent stabbing incidents on China’s subways and in parks, the Japanese embassy in China has urged its citizens to remain vigilant.”

Many Japanese commentators on social media and in the mainstream media blamed the incident on anti-Japanese education in Chinese schools and propaganda by Chinese state media.

In this case, “education” appears to mean teaching the history of Japanese aggression against China, including the infamous Nanjing Massacre, while “propaganda” appears to mean stating China’s positions on the disputed Senkaku Islands, Taiwan, and other foreign policy issues.

Meanwhile, as Western politicians intensify their anti-China rhetoric, indiscriminate violence against Chinese people continues in the West. On July 1, the New Zealand Herald reported that a woman on a bus in Auckland shouted racist slurs at a 16-year-old Chinese New Zealand boy and attacked him with a metal rod.

The boy had three broken teeth and two more damaged. Photos apparently taken on a mobile phone by another passenger showed his face covered in blood and his hands raised to protect himself.

The photo shows other passengers, some of whom are reportedly of Chinese descent, but not the attacker. Only one of the passengers intervened in the apparently unprovoked and racially motivated attack. The upper part of the boy’s face has been blacked out to protect his privacy. Police said they are doing all they can to find the attacker.

The next day, in a short video report published by the Global Times titled “President Hu Speaks,” Hu Xijin wrote:

“Last Friday in Auckland, New Zealand, a 16-year-old Chinese student was suddenly attacked with an iron bar on a public bus, leaving him with severe facial injuries and losing three teeth. Only a 75-year-old man intervened to protect the victim. According to Chinese media reports, the elderly man was also Chinese. When the assailant tried to get off the bus, the injured Chinese student begged the driver not to let him off, but the driver still opened the door.

“Despite there being more than 10 people on board the New Zealand bus, the female attacker escaped and has not been arrested. The weak response to the attack of female passengers on public buses is a disgrace to New Zealand civil society.”

Perhaps, but it’s not that simple. In a more detailed article published on Australian news site news.com.au, also on July 2nd, senior reporter Frank Chan wrote:

Details of the attack, which allegedly took place on Friday morning – the Maori New Year holiday – were first shared on Chinese social media platform WeChat by local news blogger Mao Peng.

Chinese-language reports said the boy was on a bus heading from East Auckland to the city when he was attacked by “a woman in her 40s who appeared to be Maori”.

A 75-year-old Chinese man who was on the bus and rushed to the boy’s rescue said that despite his cries for help, “more than 10” Chinese people on the bus “just sat in their seats and did nothing.”

Photos attached to the report show a 75-year-old man and a boy trying to grab the iron bar from the woman, with the boy’s and other passengers’ faces obscured.

Following the knife attack on an American teacher in Jilin province, U.S. Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns wrote to X:

“I am outraged and deeply saddened by the stabbing of three Americans and one foreign resident in Iowa in Jilin Province, China. U.S. Consular officers visited the four today in the Jilin Hospital where they are being treated. We are doing all we can to help them, and we hope they will make a full recovery.”

Burns is not the only one deeply troubled by what China officially claims are isolated incidents against American citizens: thousands of anti-Asian hate crimes and incidents have been reported in the US since then-President Donald Trump referred to COVID-19 as the “Kung Fu Flu” and the “China Virus” in June 2020.

Documented investigations of the attacks have included stabbings, slashing with box cutters, punching, kicking, stomping, and even racially motivated murders, including hitting a grandmother over the head with a rock and pushing a young woman in front of a subway train, as well as at least one mass shooting.

While the number of these crimes and incidents has dropped significantly since President Trump left office, AAPI Senior Research Fellow Janelle Wong said: [Asian American and Pacific Islander] “Anti-Asian hate crimes are often linked to national security and other U.S. foreign policy issues that bring increased attention to Asian Americans in the United States,” Data told NBC News last year.

Amid fears of another surge in attacks if Trump is re-elected, Wong said, “We can expect to see another increase in attacks at some point depending on the domestic and international situation and the extent to which the region in Asia is perceived as a threat to the United States.”

“The risks Chinese people face abroad are much greater than the risks foreigners face inside China,” Hu Xijin wrote on Weibo. That’s probably true. But given what’s happened in the U.S. during the pandemic, it’s somewhat hopeful that Chinese internet platforms and news media are trying to silence extremists and defuse racist attacks against foreigners in China before they become an epidemic.

Follow this writer on X: @ScottFo83517667