In late June, a Chinese man stabbed a woman from Japan and her child at a bus stop for a Japanese school in the eastern city of Suzhou. Two weeks earlier, four foreign teachers from a U.S. college were attacked by a knife-wielding local as they strolled through a park in the northeastern town of Jilin. In a country where violence against foreigners has been practically unheard-of in recent years, the assaults have led to some uncomfortable soul-searching among a shocked Chinese public.

Are hard economic times fueling a dangerous spike in nationalism? some ask in online debates. Has the Chinese school system, with its focus on patriotism, fed people bad ideas? they wonder. Occasionally, a bold voice risks angering China’s censors by posing an even more sensitive possibility: Could the government be to blame?

Chinese state media bombard the public with warnings about foreign spies, plots, and threats, as well as deluging them with negative portrayals of the United States, Japan, and other countries. “What impact,” one commenter on the social-media platform Zhihu asked, will this “false and one-sided content have on ordinary people’s cognition and social trends?”

That’s a salient question. Some dissonance has emerged in China’s mixed messaging and contradictory aims. In recent months, senior Chinese officials have made a strenuous effort to appear welcoming to foreigners. The Chinese leader Xi Jinping took the unusual step of meeting with American CEOs in San Francisco last November, and again in March, in Beijing, to convince them that China is as open for business as ever. Xi also recently said he’d like to see 50,000 American students studying in China over the next five years.

Yet such aspirations seem detached from the reality of Beijing’s growing hostility toward the U.S. and its partners. Fewer than 900 American students were studying in China this past year, according to the U.S. State Department—down from 15,000 a decade ago. Foreign investment in China sank to a 30-year low last year.

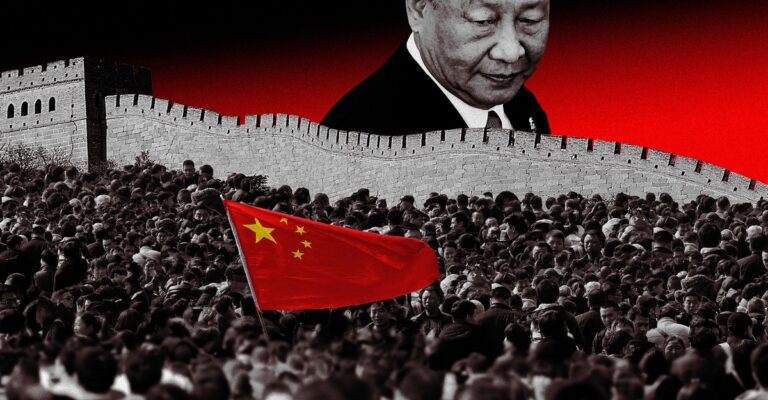

In essence, Xi is building a new Great Wall. His does not exist physically, in stone, but is designed to serve the same purpose as the old one—to shield the nation from foreign threats. Today’s invaders infiltrate not as warriors on horseback but as visitors on planes, or as contacts and connections forged through data networks, media reports, even personal conversations. To protect China from these modern marauders, Xi is raising a novel type of fortification made up of digital firewalls, legislation, and intensified repression.

This deeper trend means that China’s connections to the outside world are withering. As China and the West “decouple,” in the diplomatic jargon, the best hope for stabilizing their fraught relations remains with continued exchange—the face-to-face encounters involved in business deals, tourism, and education programs. If, instead, mutual trust between China and the West further deteriorates, the social glue binding them may not prevent a descent into geopolitical confrontation.

The cost to China could be steep as well. Arguably, no other country has benefited more from a globalized world order. To withdraw from that, even partially, will put those benefits at risk and inhibit China’s further rise.

China’s economic slowdown is contributing to these frayed ties by making foreign investors cautious. The legacy of China’s self-imposed isolation during the coronavirus pandemic is a factor, too. But Xi’s security-obsessed policy is a major—perhaps the primary—cause. Xi aims to expand China’s global influence, but in crucial ways, he is engineering a turn inward. He replaced the Communist Party’s long-cherished guiding principle of “reform and opening up,” which encouraged China’s integration into the global economy, with one of “self-sufficiency,” a more autarkic, security-first approach of substituting domestic production for foreign trade.

Xi also deliberately fuels nationalist anger over perceived Western slights to gin up popular support. The need to maintain his grip on Chinese society means that he exerts ever-greater control over the information that flows in and out of the country.

To prevent such unwanted intrusions, Xi reinforced China’s internet Great Firewall to screen his populace from such foreign dangers as democracy and K-pop. Xi also created new regulations to give his surveillance state even greater power. In February, for instance, the Chinese government broadened the types of information that it considers a national-security risk to include something called “work secrets,” an ill-defined term that appears to mean commercial data or knowledge that, if revealed, could harm China’s interests.

This focus on security “is having a chilling effect on foreign business,” James Zimmerman, a Beijing-based lawyer and a former chair of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, told me. “In everything you do, in the back of your mind, you have to be concerned about potentially crossing a red line.”

The task of stamping out foreign threats is not confined to the state. It’s a civic duty. “The entire society must mobilize against espionage,” the Ministry of State Security, China’s top spy agency, told the public last year through its social-media account. To help citizens spot bad guys, the ministry issued a series of comic strips of supposedly real-life heroics. One depicts a female agent tracking down a blond man and wrestling him to the ground. Another shows a different blond man isolated in a dark room—such xenophobia, racial profiling even, is a consistent feature—after being detained as a spy suspect.

In this tense atmosphere, some foreigners now prefer to avoid traveling to China. German inspectors for the pharmaceutical industry, fearful of being arrested as spies, are refusing to visit China and vet its factories, which has caused disruption to medical supplies. Dan Harris, a lawyer who focuses on business in China at the firm Harris Sliwoski, told me that he hardly ever had clients inquiring whether it was safe to travel to China before, but over the past two years, he’s had about 20 such requests. “People don’t trust China anymore,” he said.

The chances that the Chinese government will toss a visiting CEO in a dungeon are probably low. But the fear is not unfounded. Well-publicized detentions and mistreatment of foreign nationals, together with China’s opaque legal procedures, have made the authorities appear capricious and abusive. In March last year, a Japanese pharmaceutical executive named Hiroshi Nishiyama disappeared. The Chinese foreign ministry revealed that he was suspected of espionage; Nishiyama remains in detention while Chinese authorities decide whether to prosecute him. An Australian journalist named Cheng Lei spent three years in a Chinese cell. Her crime was to break an embargo on the release of a government document by a few minutes. For that, she endured six months’ isolation in a small room with a tiny window that was opened for just 15 minutes a day.

“I tell officials here that their arbitrary actions against foreign companies and businesspeople run counter to their stated desire for foreign investment and tourism,” Nicholas Burns, the U.S. ambassador to Beijing, told me. Among the hazards for Americans in China, he noted the “increased scrutiny of U.S. firms, the risk of wrongful detention,” and the issuing of “exit bans on U.S. citizens without a fair and transparent process under the law.”

Chinese citizens who have extensive contact with foreigners are also under suspicion. An official at a top anti-graft agency warned that the country’s diplomats will face extra vetting because of their frequent interactions with foreigners. “The risk of them being infiltrated, instigated, and roped into corruption is relatively high,” the official said. In February, the Ministry of State Security warned that Chinese students studying abroad should be vigilant of foreign spies seeking to recruit them.

Understandably, some Chinese people have become fearful of engaging with foreigners who might be politically sensitive. Last summer, I was invited with other journalists from American media organizations to a dinner with visiting U.S. academics who were meeting counterparts at major Chinese universities. I had expected at least some local scholars to join this informal gathering, but none did.

Informal ties are unraveling, too, as fewer people move in and out of China. The country largely missed out on the post-pandemic resurgence in international travel. Last year, the number of scheduled international flights from China reached just 40 percent of their 2019 total, according to the aviation analytics firm Cirium, and border crossings by foreigners were down to less than 40 percent. Chinese nationals themselves took only a third as many outbound trips last year as they had in 2019 (excluding travel to Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan).

Some expatriate communities in China are shrinking. In 2023, 215,000 South Korean citizens lived here, down from 350,000 a decade earlier. The number of Japanese nationals has also declined, from some 150,000 in 2012 to about 100,000 last year. A recent survey of U.S. companies from the American Chamber of Commerce in China found that a third of respondents said their top candidates were unwilling to move to China, a problem never cited in pre-pandemic times.

As the recent wave of seemingly random attacks suggests, xenophobia is not limited to the Chinese security state. Rising nationalism has made the populace at large more suspicious of things foreign. Official policy and popular sentiment cross-fertilize a dangerous antipathy.

China’s richest man, Zhong Shanshan, the founder of the bottled-drinks company Nongfu Spring, recently faced online accusations of disloyalty. The red caps on his bottled water, social-media posters complained, were similar to the sun on the national flag of Japan, suggesting a closet sympathy for China’s regional rival. Zhong’s critics also speculated that his company’s assets could be transferred to the U.S. because his son holds an American passport. The fact that this criticism was permitted on the carefully censored Chinese internet implies that the authorities tacitly approved.

China’s digital nationalists do not, of course, speak for all Chinese people. I have never experienced hostility from regular people (as opposed to officials) in my many years in China, yet the smaller number of foreigners now coming here is very evident. The bureau in Beijing where I renew my resident visa always used to be jam-packed, with hours-long waits to get paperwork done. At our most recent visit, in October, my wife and I were the only ones there.

Beijing’s impulse to shore up its regime by sealing China off from the outside has deep historical roots. The Great Wall, now simply a tourist destination, was constructed mainly by the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). That barrier was a response to a serious security threat. Nomadic hordes from the Central Asian steppe routinely mounted raids across China’s long northern frontier; the walls were the dynasty’s effort to defend its empire. But protection against external threats can do little to forestall internal failures. Finally, in 1644, amid the Ming’s collapse, a Chinese general guarding the northern frontier was so dismayed by the domestic chaos that he allowed a Manchu army to slip through the Great Wall and form a new dynasty, the Qing.

Modern efforts to exclude foreign influence and limit exchanges may be similarly undermined. Knowing a life less immured, many Chinese people do not relish seeing new walls go up. Much of the social-media response to the recent stabbings of foreigners expressed dismay that they might scare off foreign business, and many posters championed the brave Chinese woman who confronted the assailant at the Japanese-school bus stop and died from her own wounds.

Some of them also made concerned reference to the Boxer Rebellion, a popular movement that sought to purge China of foreign influences at the turn of the 20th century by targeting missionaries and besieging diplomatic legations. That episode ended in catastrophe, when an allied military force that included the U.S. and Japan invaded China and chased the Qing’s empress dowager from the Forbidden City. That dire outcome—when nativist violence provoked geopolitical retaliation—has an ominous resonance today.

So far, Xi has been unwilling to temper his government’s xenophobic rhetoric or rein in his security state to avoid such geopolitical fallout. He appears to believe he can erect barriers that protect his political interests but permit the foreign capital and technology China still needs. From outside, however, China appears to be sinking into isolation and paranoia that endanger the country’s future. Xi is building walls when he should be building trust.