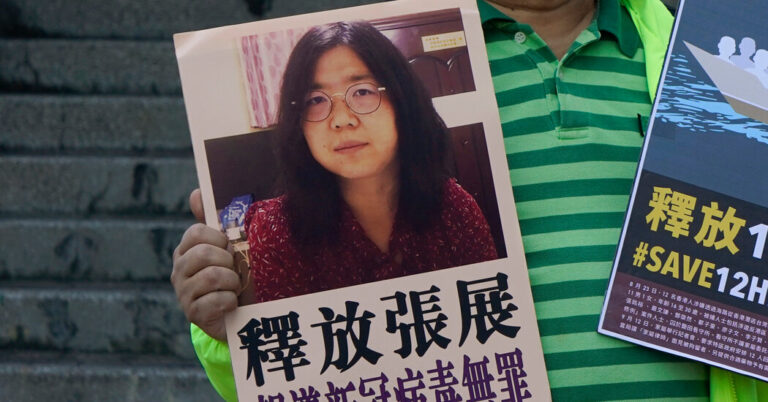

Zhang Zhan, believed to be the first person to be jailed for documenting the early days of the coronavirus pandemic in China, was scheduled to be released on Monday after serving a four-year sentence.

But in a sign that the Chinese government remains keen to suppress public discussion of the outbreak, it was unclear as of Monday night whether Zhang, 40, had actually been released. . Zhang Keke, a lawyer who represented Zhang during the trial (the two are not related), said he had been unable to contact his mother throughout the day. Shanghai prison officials declined to comment when contacted by phone.

“Even if she completes her sentence, there are doubts about the Chinese regime’s willingness to return her to freedom,” the international media watchdog group Reporters Without Borders said in a statement days before her scheduled release. Stated. The organization, which awarded Zhang the Freedom of the Press Award in 2021, noted that imprisoned journalists in China are often kept under surveillance.

Zhang was an early symbol of the distrust many Chinese felt toward the government’s response in the early days of the pandemic and the hunger for unfiltered information. A former lawyer from Shanghai, she traveled to Wuhan, where the virus was first detected, in early 2020 as a self-proclaimed citizen journalist.

For months, she shot amateur, often shaky videos that contradicted the government’s narrative of a smooth and triumphant response to the crisis. She visited a crematorium and a crowded hospital with beds lying in the hallways. She videotaped the city’s empty train stations and attempted to interview residents about the lockdown, but many ignored her or requested her anonymity, as she appeared to fear reprisal. did.

Friends said she had never reported, but was motivated by her Christian faith and anger at the government’s one-sided rhetoric.

“If we just wallow in sadness and do nothing to change this reality, our emotions will become cheap,” Zhang said in a video.

The government was so busy containing the infection and keeping the city of 11 million people under lockdown that it narrowly missed independent reporting on the outbreak for some time. Some of the videos Zhang posted on Chinese social media were censored, but he also uploaded them to YouTube, which is banned in China.

But soon, a crackdown on independent reporting began in earnest. Other citizen journalists also began to disappear. Despite acknowledging the risks, Chan continued to post about the lockdown and its aftermath even after it was lifted in April 2020. Then, in May of that year, she was arrested and brought back to Shanghai.

Still, Zhang remained defiant even during his detention. Her lawyers say she began several long hunger strikes and became so weak that she used a wheelchair to attend her trial. Her lawyer says authorities force-fed her through her feeding tube.

Zhang was sentenced in December 2020 to four years in prison for “picking fights and provoking trouble,” a blanket offense often used by the government to silence critics.

Zhang’s plight quickly became a rallying cry for human rights activists and foreign governments who criticize China’s suppression of free speech. When news broke in 2021 that Zhang was in critical condition, the US State Department called for her immediate release, as did groups such as Human Rights Watch.

However, many people within China who tried to defend Zhang appear to have become targets themselves. Her brother, who had used Twitter, which is banned in China, to share her memories of her childhood and rally international support for her, was largely silent. Many of his posts were later deleted. One of the lawyers who represented her was banned from practicing law for her because of his involvement in another human rights case.

Asked about Zhang’s case at a regular press conference scheduled for Monday, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said he had no information about her case, but said those who violated Chinese law should be punished. Stated.

Zhang’s last video from Wuhan showed her chatting with unemployed migrant workers and thinking deeply about the usefulness of what she was doing.

“Actually, I wasn’t sure what to say today,” she said. “But these people, these things, always push me forward beyond despair and fear and push me to keep paying attention to them and keep speaking up for them a little bit.”