China is expected to benefit from Vietnam’s unprecedented political turmoil amid months of infighting and internal maneuvering within the ruling Communist Party and signs of growing authoritarian tendencies in Hanoi, observers say.

Bill Hayton, an associate fellow at the Chatham House Asia Pacific Programme, described the turmoil as “unprecedented” and said it showed Vietnam’s politics were in a “constant state of flux”.

“I don’t know if this is the end of the battle or an intermediate stage,” he said. “At the moment it seems like the hardliners – the police chief and the Leninists – have won the battle.”

Apart from Lam’s promotion, General Luong Cuong, 67, director of the Vietnam People’s Army’s Political General Department, was promoted to replace Truong Thi Mai at the Central Committee plenum on May 18. The party appointed four new members to its Politburo last month.

Heiton said Vietnam’s new leadership seemed willing to “sacrifice some economic growth for tighter political control” and that the fierce power struggle could have far-reaching implications for the country’s future development.

“Vietnam’s integration into the world will probably slow as it follows China’s lead and becomes politically inward-looking, focusing more on political security and regime survival than economic development,” he said.

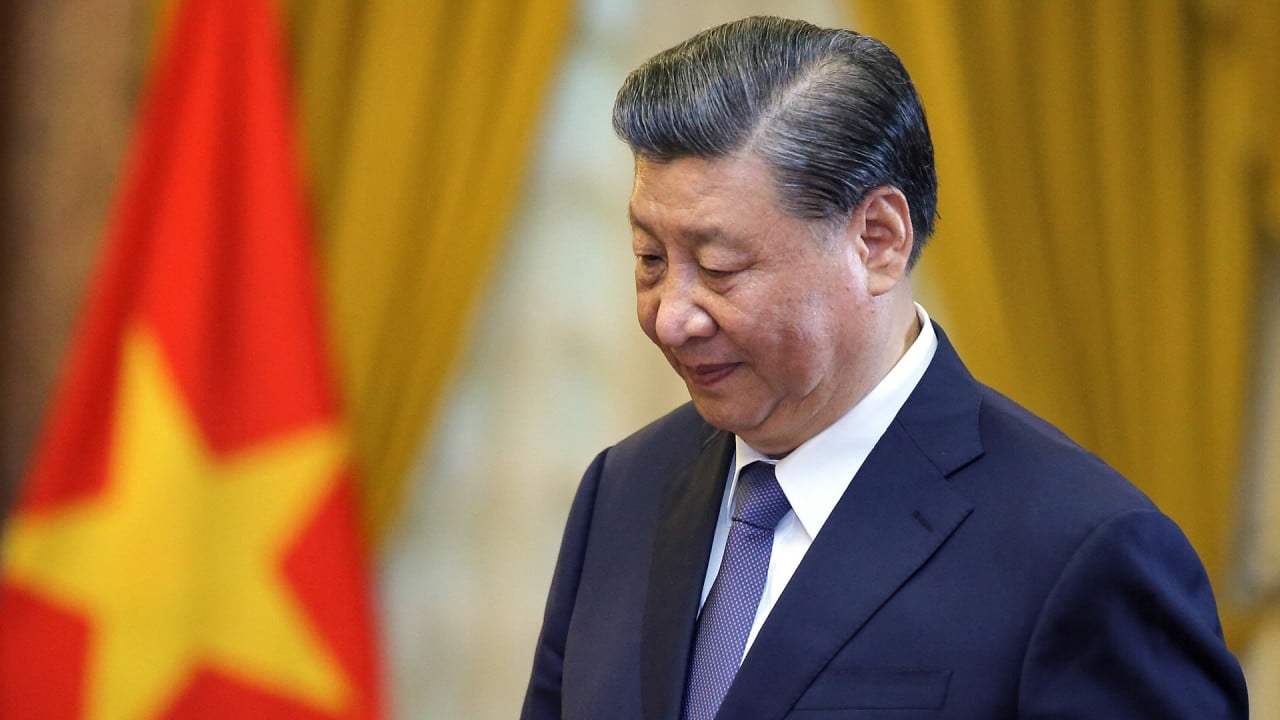

Mr. Heighton said Beijing, which has been closely watching Vietnamese politics, would be pleased with the personnel changes.

“It’s exactly them. [Chinese officials] They want a hardline group that is politically like-minded. [President] “Xi Jinping and China are far more skeptical of the West and have followed many of China’s hardline policies, emulating its anti-corruption campaign and closing off information access to outsiders,” he said.

Mr. Hayton said Vietnam was likely to turn its back on the United States as those in power became increasingly suspicious of the United States and its role in promoting democracy and openness.

“It’s clear that their leadership is pro-China. They will insist that Vietnam remains neutral and that its policies will not change. But the leadership will become more authoritarian and will find it harder to cooperate with the West than it would with China or Russia,” he said.

Zhang Mingliang, a regional affairs expert at Guangzhou’s Jinan University, said the unusual political upheaval in the Southeast Asian neighbour has raised several factors favouring Beijing.

“There are few signs that the internal conflict has already peaked and is expected to continue, and may intensify further ahead of the power transition in 2026. This signals a rift in Vietnam’s top leadership and could affect the ruling party’s ability to work together with China on the South China Sea dispute and other issues,” he said.

“Vietnam has always been a thorn in China’s side, but worsening political turmoil could distract the Hanoi leadership and make it more difficult to achieve unity on foreign affairs, which would weaken Vietnam’s China policy and benefit Beijing,” he said.

In her inaugural speech after becoming Vietnam’s third president in less than two years – her two predecessors resigned after citing “violations and misconduct” – Lam vowed to “persist with determination and persistence” in the fight against corruption.

Instead, Lam focused on party leadership and control, vowing to “strengthen order and discipline” and to “resolutely counter and defeat ‘self-evolution,'” which according to Heighton is the tendency of individuals to put themselves above the party.

Zhang said Lin’s ideologically focused and combative rhetoric underscored Hanoi’s priority of political stability, which can only be achieved through close cooperation with Beijing.

“With greater party control and protecting the regime becoming the slogan within the ruling party, Vietnam is likely to distance itself from the West, which would be good news for China as well,” he said.

Carl Thayer, professor emeritus at Australia’s University of New South Wales and an expert on Southeast Asia, said the leadership turmoil was unlikely to affect Vietnam’s foreign policy or balancing act between Beijing and Washington.

“For more than 30 years, Vietnam has been steadily diversifying and multilateralizing its foreign relations. Vietnam has been and will continue to be committed to building all-round cooperative relations with partner countries, especially the seven comprehensive strategic partners – Russia, China, India, South Korea, the United States, Japan and Australia,” he said.

“One sign of Vietnam’s balancing act is that while exports from China to the US are declining, exports from Vietnam to the US are increasing based on increased exports from China to Vietnam.”

Tuong, a protégé of Trong and the youngest member of Vietnam’s powerful Politburo, visited China twice last year to try to ease Beijing’s concerns about Vietnam’s improving ties with the United States, Japan and their allies amid widening rifts over maritime disputes.

Nguyen Kak Giang, an analyst at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, also downplayed the impact of political turmoil at the top on the country’s overall direction.

“Vietnam is becoming increasingly authoritarian, but its open economy and multilateral foreign policy have prevented it from becoming an inward-looking nation,” he said. “The current unrest may undermine Vietnam’s efforts to respond to the South China Sea situation, but it is unlikely to change its current approach.”

But Zhang also warned that excessive internal strife and power struggles could undermine Vietnam’s political stability and Beijing should remain vigilant because “an unstable Vietnam is no boon for China.”

But external factors, such as a possible incident with Beijing in the South China Sea, could disrupt Sino-Vietnamese relations and move Hanoi closer to Washington’s sphere of influence again, he said.

Heighton also said Beijing should tread carefully in its maritime disputes with Hanoi.

“In a way, this is an issue where China is shooting itself in the foot because it has taken a hardline stance on the South China Sea and does not recognise the legitimacy of other countries’ claims. That is undermining Vietnam’s Communist leadership,” he said.

“If China is wise, it will find a middle ground with Vietnam and better secure its position as a friendly country to Hanoi,” he suggested.

“Anything that the Vietnamese leadership sees as unpatriotic or too subservient to China will be a big enemy to Vietnam. So if Vietnam is humiliated by China in the South China Sea or elsewhere, that will give it an excuse to rebel against the leadership and provoke a backlash that is probably against China’s real interests,” Heighton said.

The political turmoil has raised concerns among foreign countries about the true motives of the anti-corruption campaign, but it certainly isn’t over.

Zachary Abuza, a professor and Southeast Asia expert at the National War College in Washington, said this was the most politically turbulent period in Vietnamese political history.

“[Lam] “The president has used corruption investigations as a weapon to systematically eliminate his political opponents,” Abuza said.

Lim is vying to become the country’s next top leader when Chung, 80, is expected to retire at the party’s five-year congress in early 2026.

“This clearly undermines Vietnam’s selling point to foreign investors of offering political stability and predictability. However, Vietnam’s political system is based on collective leadership, giving it a degree of resilience,” he said.

“But the infighting is not over yet and we expect more heads to fly by the 14th. [party] It is scheduled for Congress in January 2026.”