PUBLISHED

July 20, 2025

KARACHI:

In May this year, India’s prized Rafale jets — once paraded as the crown jewels of its military modernisation — fell from the skies during an unprovoked escalation with its adversary, nuclear-armed neighbour, Pakistan.

What followed was less a military debrief than a media spectacle, as New Delhi worked tirelessly to rebrand the skirmish as a triumph, spinning the narrative long after the dust had settled.

Two months after the nuclear-armed rivals edged toward open conflict, India’s Deputy Chief of Army Staff made a revelation — not in a formal strategic forum or before an international audience, but while addressing a gathering hosted by the Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry. During ‘Operation Sindoor’, he claimed, India had confronted not one but three adversaries – Pakistan as the “front face,” with China and Türkiye allegedly providing critical support to Islamabad behind the scenes.

Lieutenant General Rahul R. Singh, stitching together India’s latest storyline around Operation Sindoor, reached for an ancient analogy to make his point. Citing The 36 Stratagems, a Chinese military classic, he invoked the tactic of “killing with a borrowed knife” — the idea of striking an enemy through a proxy. China, he suggested, had done precisely that, using Pakistan as its instrument to inflict damage on India while avoiding direct confrontation.

“China would rather use the neighbour to cause pain [to India] than get involved in mudslinging on the northern border,” he told the gathering — a line that neatly folded geopolitics into parable.

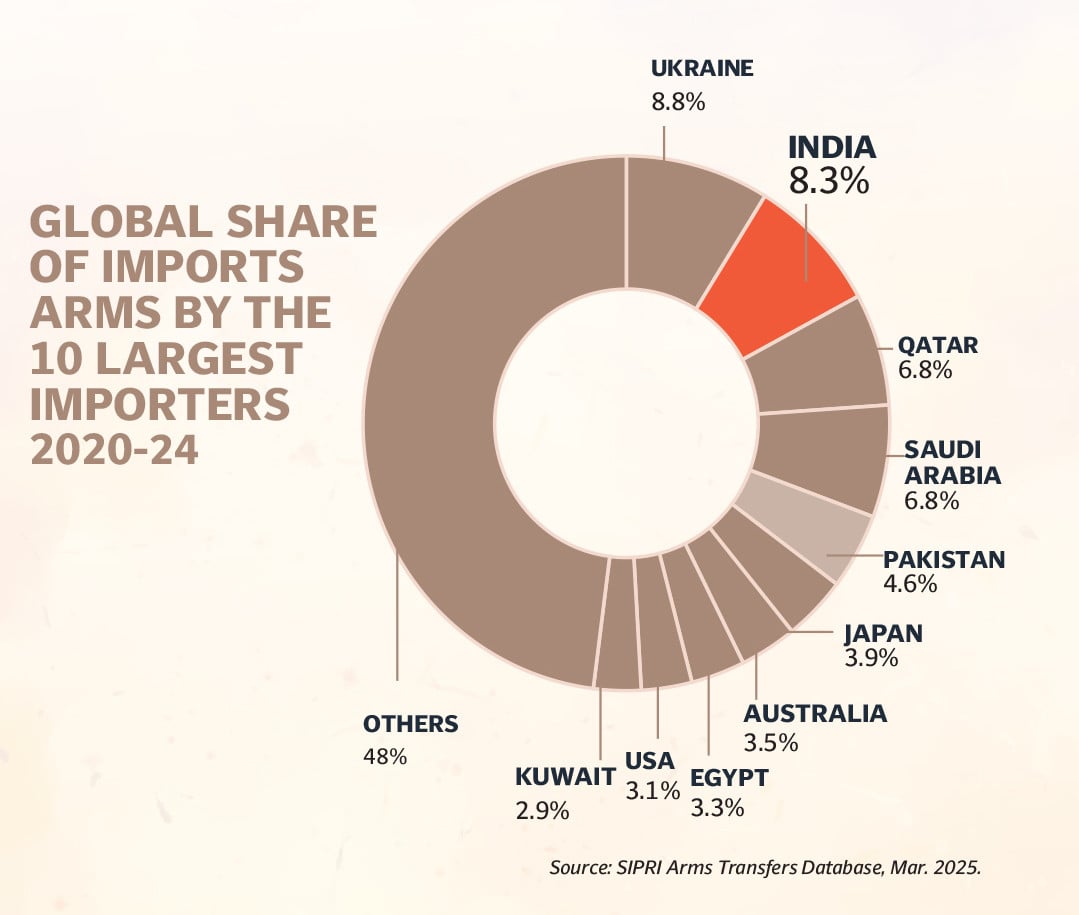

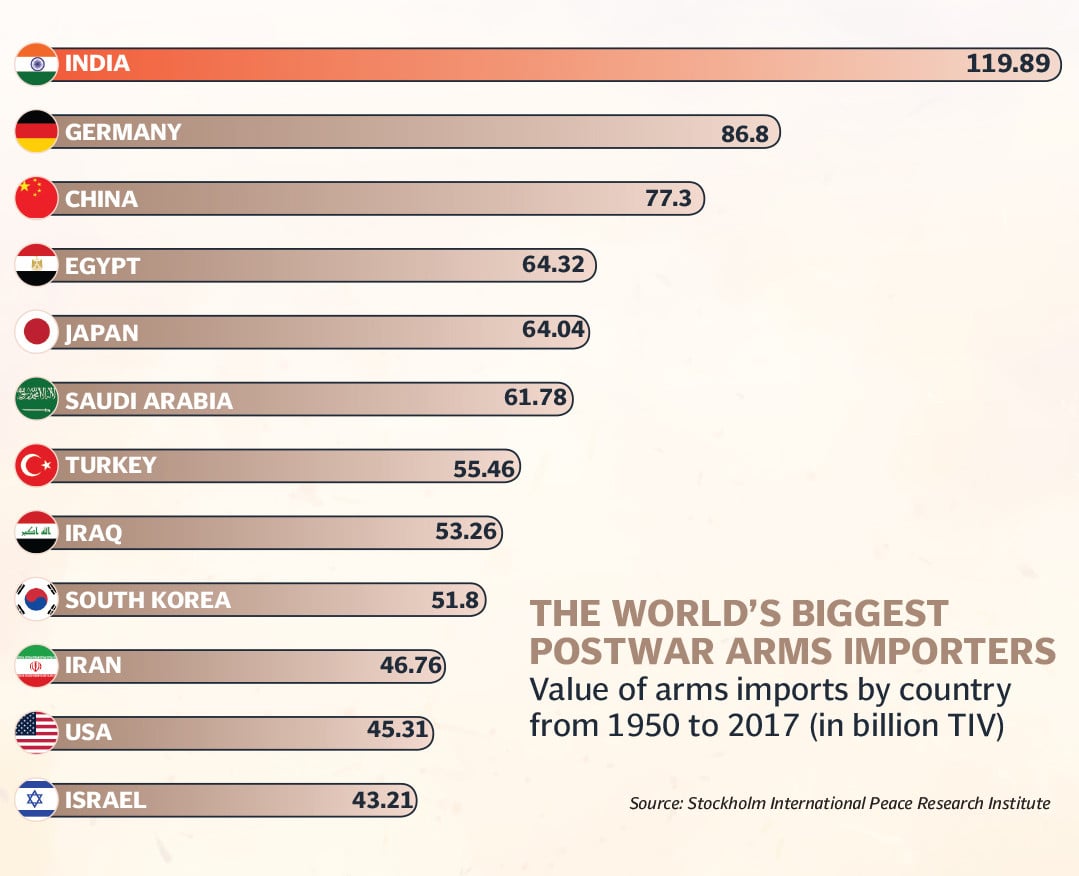

The officer went further to claim a-known fact that Pakistan is heavily dependent on Chinese military hardware. “If you were to look at statistics in the last five years, 81% of the military hardware that Pakistan gets is from China.”

By that logic, experts point out, India too was effectively backed by France — and even Russia — given that the weapons deployed against Pakistan were sourced from those very countries.

Rafale jets and their SCALP-EG missile systems were used in strikes that left scores of Pakistani civilians dead. The use of these French-supplied arms, critics argue, sits uneasily with the European Union’s own arms export regulations, which prohibit the transfer of weapons likely to be used in acts of aggression or against civilian populations.

Both the Rafale aircraft and SCALP-EG missiles are exported under the EU’s Common Position 2008/944/CFSP, which outlines eight legally binding criteria that member states must apply when granting arms export licences. These are not advisory guidelines, but enforceable obligations under EU law. Failure to comply with these criteria, experts said, not only undermines EU credibility but may also constitute a breach of international humanitarian law.

Hassan Akbar, a former Pakistan Fellow at the Wilson Center, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, described the latest iteration of India’s narrative as “convoluted.” “It is being peddled by New Delhi in an attempt to explain away the failures of its military against a smaller adversary, and to paint Pakistan as a proxy of China—particularly for Western audiences,” he said.

Pakistan’s success, he noted, was primarily the result of indigenous advancements that enabled its fighter jets, radars, electronic warfare platforms, and sensors—sourced from various countries—to operate seamlessly in a networked, multi-domain environment.

“If one follows India’s logic, then Pakistan wasn’t just fighting the Indians, but also the Russians, the French, and others from whom India procures its defence equipment. It’s evident that India’s narrative lacks both evidence and coherence,” said Hassan.

But India has, by now, earned a reputation for narrative-building. Investigations by the Brussels-based EU DisinfoLab previously uncovered a sprawling network of fake news websites linked to New Delhi — suggesting that the Modi government has long been engaged in shaping favourable perceptions abroad, particularly to keep Western allies firmly in its corner. Its latest attempt to rope in China and Türkiye — apparently to deflect international embarrassment over Operation Sindoor — appears to follow that same well-worn playbook.

“Shifting Indian narratives around Operation Sindoor — particularly the effort to draw China and Türkiye into the equation — only undermines whatever credibility is left,” said Dr Talat Wizarat, former head of international relations at the University of Karachi. For a country that claims regional power status, she added, “India has shown remarkably little control over keeping its own storyline steady and consistent.”

Shifting lines in the sand

In the aftermath of Operation Sindoor, India was drawing lines in the sand—each washed away for the next. What began as a brief military flare-up with Pakistan quickly morphed into a campaign of narrative consolidation, where the facts of the operation were overshadowed by the story New Delhi wanted the world to see and believe. The Modi government packaged the operation as a masterstroke in strategic deterrence, but the cracks were visible from the start.

India’s own Rafale jets crashed, yet the official line barely acknowledged that, choosing instead to inflate the scale and scope of the threat. So extreme was the narrative that India claimed it wasn’t merely facing Pakistan but a coordinated axis including China and Türkiye—an assertion that lacked substantive proof and seemed more geopolitical theatre than military assessment.

This reframing allowed India to sidestep uncomfortable scrutiny over intelligence gaps and civilian casualties. The use of French-supplied Rafales and missile systems against Pakistani targets, some of which struck civilian zones, also threw a wrench into the European Union’s arms export standards, which ostensibly forbid such end-use. In Brussels and Paris, the silence was telling. India’s post-operation messaging relied heavily on volume and repetition rather than verifiability, in keeping with its now-familiar strategy of managing perception rather than consequence.

Critics argue that Operation Sindoor wasn’t a turning point in regional security dynamics but rather a continuation of a pattern – military engagement followed by information warfare, where ambiguity is weaponised and accountability conveniently disappears.

“The fact that the Indian government had to offer so many versions of what it called a victory over Pakistan suggests there was no real victory to begin with—if any at all,” quipped Wizarat, a keen observer of regional affairs.

The great embarrassment

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has developed a reputation for his showmanship. After every major international event, the BJP leader tends to fire off posts on X, formerly Twitter, calling most — if not all — foreign leaders his dear friends. His image as India’s prime minister, experts argue, has been carefully choreographed. At the consecration of the Ram temple — built on the site of the Mughal-era Babri Masjid — it was not the high priest but Modi himself who led the ceremony, performing rituals traditionally reserved for Hindu religious leaders.

The aftermath of Operation Sindoor has, in many ways, proved an embarrassment for Modi’s curated image — both at home and abroad. “The chorus of critical voices has been louder,” said one expert, who did not wish to be named. The extent of the unease was captured in a recent post by Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, who shared a clip of US President Donald Trump suggesting that India lost five jets during the escalation.

“Modi ji, what is the truth about the five jets? The country has the right to know,” Gandhi posted — a pointed jab at his political rival and India’s sitting prime minister. But the embarrassment hasn’t been confined to India alone.

Shares of Dassault Aviation — the French manufacturer of Rafale jets used by India during ‘Operation Sindoor’ — slumped on European stock markets. A symbolic fall, some noted wryly, echoing the very aircraft reportedly brought down by Pakistani fire.

“New Delhi’s credibility as a country claiming military superiority over its adversaries came crashing down with those jets. Had it maintained a consistent narrative, the embarrassment might have been avoided,” said Wizarat.

Akbar, in his precise assessment of Modi’s predicament, noted — “India’s political and military leadership has been trying to sell their shortcomings during the conflict as a victory to domestic audiences.”

The former Wilson Center fellow’s view rings true in light of Prime Minister Modi’s actions. Shortly after the operation — and despite the humiliation of Indian fighter jets smouldering in the wake of Operation Sindoor — Prime Minister Narendra Modi, as The Wire reported, positioned himself squarely at the heart of a triumph he had all but choreographed. His public addresses became rituals of symbolism, thick with invocations of sindoor, however, conspicuously devoid of any reference to the militants behind the Pahalgam attack. Then, on 12 May — a full forty-eight hours after US President Donald Trump brokered a ceasefire between India and Pakistan — Modi launched into an unrelenting campaign blitz — nine rallies in eight days across six states, as if electoral momentum could be spun from the ashes of a fractured narrative.

Wizarat described the entire operation as meticulously timed for electoral gain. “It has become almost predictable,” she noted, for India’s political leadership to invoke the threat of Pakistan — or the spectre of Muslims — in the run-up to elections, as a way to consolidate support among its Hindu base.

The China conundrum

They say one lie begets another — a spiral of invention to conceal what never truly was. India now finds itself tangled in precisely such a mess. Despite New Delhi’s persistent evasions over the fate of its downed fighter jets during the skirmish, new reports have emerged confirming what the government has long tried to bury — that its prized aircraft were indeed shot down — not by a technologically superior Western force, but by Chinese-made weapons in Pakistani hands.

Armed with that uncomfortable truth, Indian officials have begun aiming their rhetorical fire at Beijing, painting China as the main villain in the conflict. However, experts argue that the accusation stretches the boundaries of credibility. “The sale of arms — however consequential — does not make China a combatant, any more than France or Russia were deemed parties to the conflict for supplying India with the very weapons it used against Pakistan,” said Wizarat.

India, Wizarat argued, must move past its obsession with outpacing China in the regional — or even broader global — power race. “If anything, the recent escalation between Pakistan and India has shattered the myth of Western superiority in the arms race,” she concluded.

According to Akbar, India’s attempt to reframe the narrative was less about facts on the ground and more about courting Western sympathy — achieved by invoking alleged Chinese involvement in the tit-for-tat exchanges with Pakistan.

The insult that bleeds

If the downing of the Rafales was an insult, the injury hasn’t let up — not because it must, but because India’s persistent denial and deflection keep inviting it. The most recent blow came from The Economist, which detailed an incident Indian authorities still refuse to acknowledge.

On May 7, the London-based publication reported, residents of Akalia Kalan — a village near a northern Indian airbase — were jolted awake by an unfamiliar roar and a series of explosions. A ball of fire streaked across the sky before crashing into a field. The wreckage, unmistakably a fighter jet, killed two villagers. The pilots had ejected and were later found injured in nearby fields.

India has yet to officially confirm the incident — one of several aircraft losses during a brief but intense four-day conflict with Pakistan. While New Delhi disputes Islamabad’s claim of downing six jets — including three French-made Rafales — foreign military observers, The Economist noted, have verified that at least five Indian aircraft were lost. Indian military sources have since quietly conceded losses, though they suggest operational errors, not technological failure, may be to blame.

The implications are far-reaching. According to defence experts, this was the first time advanced Chinese weapons — Pakistan’s J-10 fighters and PL-15 missiles — were deployed against Western and Russian systems.

Early assessments, The Economist reported, pointed to the superiority of Chinese systems — and possible real-time intelligence sharing from Beijing. But the most damning revelation may have come from within — a leaked recording of India’s defence attaché in Jakarta, Captain Shiv Kumar, aired in June. In it, he admits India’s initial losses were due to political constraints that barred the air force from targeting Pakistani military installations. Only after suffering setbacks, he said, were the rules of engagement expanded.

“The fact that India continues to deflect questions about gains and losses shows there were real issues not only during the operation, but also in its aftermath — where any victorious side would have flaunted its trophies right away. India, however, has been on the back foot ever since,” said Wizarat. “Instead of adding China to the equation, India must fix its own equation,” she concluded.