(Bloomberg) — The European Union is set to scold France for violating EU rules on its deficit and debt, setting in motion a process that could lead to heavy fines and complicate campaign priorities with less than two weeks to go before polls open in parliamentary elections.

Most read articles on Bloomberg

EU rules include tough measures for countries with debts above 60% of gross domestic product and budget deficits above 3%. France’s budget deficit last year was 5.5% and its debt was about 111% of GDP.

The debt will limit the next government’s ability to deliver on a series of pledges, including cutting tax revenues and reversing market-friendly pension reforms. Emmanuel Macron – With Marine Le Pen John Buffett, head of the far-right National United party, would also be cautious about any actions that could further destabilize markets that have been in turmoil since the president declared a general election a week ago.

“The National Party’s plans will be limited by financial markets,” Famke Krumbmüller, EMEIA geopolitical strategy leader at EY, said on Tuesday. “Whoever takes power will be constrained by how financial markets react to their policies.”

France is not the only country on the so-called excessive deficit procedure list, which will also include Italy and five other countries, a person familiar with the matter told Bloomberg on Tuesday, though Spain and three other countries that exceeded the 3% limit were spared.

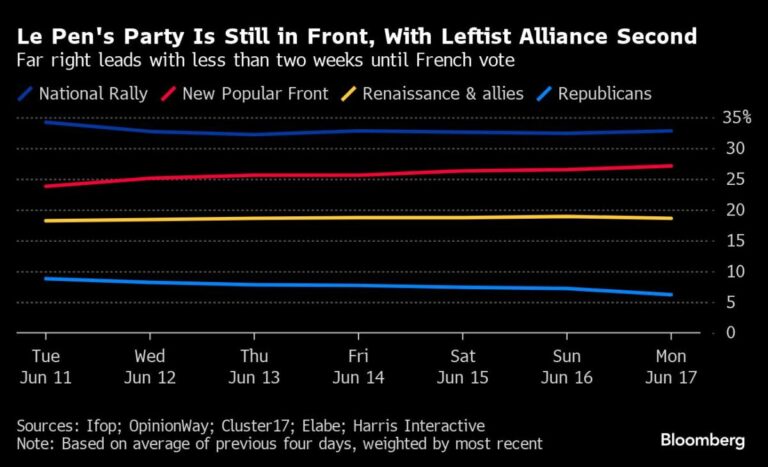

The EU rebuke comes at a crucial juncture in the French election campaign, with the Rally National expected to win 32.7 percent of the vote, according to a Bloomberg poll ahead of the June 30 and July 7 elections. The left-leaning New Popular Front, which includes the Socialists, Communists, Greens and the far-left Invincible France party, is expected to win 26.3 percent of the vote, putting Macron’s Renaissance party and its allies in third place.

The two groups best placed to form a government after the election, the New Popular Front and the National Rally, have signaled a more confrontational approach than Macron, both on spending and on confronting the EU.

An all-out conflict would draw disturbing similarities to the euro zone debt crisis, when a standoff between EU institutions and highly indebted governments sparked investor panic and sent the currency into crisis.

Since then, the EU has beefed up its crisis response tools, formalizing the conditions under which the European Stability Mechanism rescue fund and the European Central Bank can step in to calm markets with bond purchases, though the central bank says it will only do so in countries with “sound and sustainable fiscal and macroeconomic policies.”

On the eve of the EU decision, Bank of France Governor François Villeroy de Galhau renewed his calls to avoid widening budget deficits.

Respecting the people “means recognizing their real needs and not adding to yet another huge deficit that we cannot adequately fund,” he said.

Le Pen, who once campaigned for leaving the euro, has yet to lay out the details of her policy. Party leader Jordan Bardella has touted measures to further squeeze the budget deficit but has offered few details about the revenue the National Rally expects to receive from spending cuts on immigration, tackling tax evasion and reducing EU funding.

Meanwhile, the New Popular Front parties are united behind an election manifesto that includes freezing the prices of basic goods, raising the minimum wage and rejecting the austerity constraints of EU fiscal rules.

Still, if in power, parties would have to keep their voices low and avoid policies that would worsen relations with the EU, Krumbmüller said – a similar approach to that of Italy’s anti-immigration Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

France was already struggling to rein in a budget deficit after disappointing tax revenues, and before Macron called elections, his government had committed to emergency spending cuts of about 20 billion euros ($21.5 billion) this year, with even more planned for 2025.

He briefly managed to keep the budget deficit below EU limits soon after he was first elected in 2017, but heavy spending during the coronavirus pandemic and energy crisis caused it to widen significantly. His administration kept its growth forecast for this year at 5.1% and is still committed to getting below the 3% threshold by 2027.

The country’s debt is expected to peak at 113.1% of GDP next year before falling to 112% in 2027, according to the government’s long-term plan.

There are no easy political solutions to repair the deficit. President Macron has narrowed the options by insisting on a mantra of no tax increases to preserve investment and job creation, but economic growth has slowed since inflation soared. Spending cuts are also proving tricky, with both the Rally National and the Left parties leading a backlash against plans to eliminate expensive energy subsidies introduced during the crisis.

Last month, S&P Global Ratings downgraded France’s credit rating, citing the government’s failure to meet its deficit reduction plan. After President Macron called early elections, Moody’s said potential political instability was a credit risk that could affect deficit reduction efforts.

Macron’s government has made economic fears a theme of its election campaign, warning of the consequences if its opponents take power. France’s Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire warned last week that a victory for a left-wing coalition would lead to economic collapse and Brexit.

“Their plans are totally insane,” Le Maire told France Info radio. “They would guarantee downgrades, mass unemployment and withdrawal from the European Union.”

–With assistance from Samy Adghirni, Jorge Valero, Tom Mackenzie, and Zoe Schneeweiss.

Most read articles on Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP