An independent advisory committee to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday rejected the use of MDMA-assisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, highlighting unprecedented regulatory challenges for a new treatment that uses the drug commonly known as ecstasy.

Before the vote, committee members raised concerns about two study plans submitted by the drug’s sponsor, Lycos Therapeutics, with many questions centered on the fact that study participants were largely able to guess correctly whether they had been given MDMA, also known as ecstasy or Molly.

The committee voted 9-2 on whether MDMA-assisted therapy is effective, and 10-1 on whether the benefits of the proposed treatment outweigh the risks.

Other panelists raised concerns about the drug’s possible effects on the cardiovascular system and the potential bias of therapists and facilitators who might have led the treatment sessions and positively influenced patient outcomes. Instances of misconduct by patients and therapists who participated in studies also troubled some panelists.

Many committee members said they were particularly concerned that Lycos had failed to collect detailed data from participants about the abuse potential of a drug that produces feelings of euphoria and euphoria.

“I completely agree that new and better treatments for PTSD are needed,” said Paul Holzheimer, vice director of research at the National PTSD Center, one of the panelists who voted against the question of whether the benefits of MDMA therapy outweigh the risks.

“However, we also note that premature introduction of treatments may actually impede development and implementation and lead to premature introduction of treatments whose safety is not fully known, that are not fully effective, or that are not used at optimal efficacy,” he added.

The vote is not binding on the FDA, which often follows recommendations from its advisory committees. A final decision by the agency is expected in mid-August.

MDMA, or methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known as midomaphetamine, is a synthetic psychoactive drug that fosters self-awareness, empathy, and social connections.

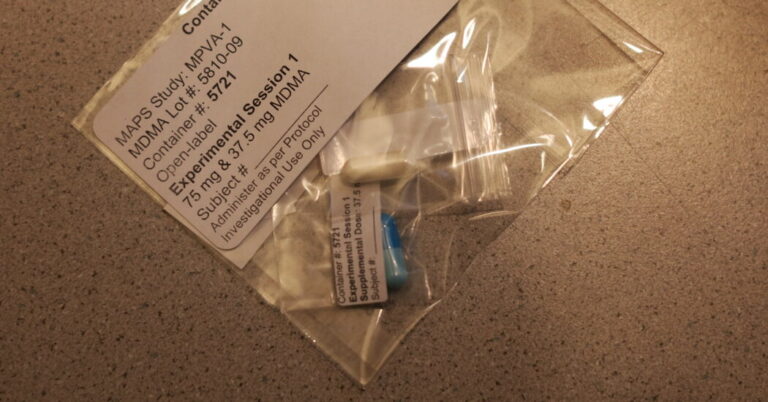

The illegal drug is classified as a Schedule I substance, defined as having no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. If approved by the FDA, federal health and Justice Department officials would have to go through certain steps to downgrade the drug, similar to the process currently in place for marijuana.

The DEA may also set production quotas for drug ingredients, similar to stimulants used to treat ADHD.

With panels focusing on topics such as “euphoria,” “suicidal ideation” and “expectation bias,” Tuesday’s daylong sessions illustrated the nuances and complexities facing regulators grappling with uncharted territory for a treatment that has only recently become mainstream in psychiatry after the country’s decades-long drug war.

To make matters worse, the FDA is a drug regulator. They don’t regulate psychotherapy and don’t evaluate drugs whose effectiveness is tied to talk therapy.

If approved, MDMA-assisted therapy would be the first new treatment for PTSD in nearly 25 years. The condition, which affects about 13 million Americans, is believed to be linked to high suicide rates among military veterans whose suffering has inspired lawmakers of both parties to spark a major shift in public attitudes toward psychedelic drug-dependent treatments.

According to a study submitted by Lycos, patients who received MDMA and psychotherapy reported a significant improvement in their mental state, and a recent drug trial found that over 86% of patients who took MDMA experienced a measurable reduction in the severity of their PTSD symptoms.

About 71% of participants saw their symptoms improve and no longer met diagnostic criteria, while 69% of those who took the placebo saw their symptoms improve and nearly 48% no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, according to the data provided.

The questions, concerns and apparent skepticism expressed by the 10-person committee echo those raised by agency officials who issued a briefing document last week aimed at helping the committee evaluate the effectiveness and potential adverse health effects of MDMA therapy.

In her opening remarks, Dr. Tiffany Falchione, chief of FDA’s psychiatry division, noted the regulatory challenges posed by MDMA, saying, “We’ve been learning as we go along,” but in testimony and staff documents, she and other FDA officials repeatedly noted that the overall findings are important and enduring.

“While the application has a number of complex review issues, it does include two positive studies showing that participants in the middromaeum arm experienced statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in PTSD symptoms,” she said, “and those improvements appear to persist for at least several months after the acute treatment period ended.”

Much of the criticism of Lycos’ study design has centered on so-called functional unblinding, an issue that affects many studies of psychoactive compounds. The roughly 400 patients who took part in the study were not told whether they were receiving MDMA or a placebo, to reduce the possibility of biasing the results, but the vast majority of patients were clearly aware of their altered mental state and were able to correctly guess which study group they were in.

The FDA, which worked with Lycos to design the clinical trials, acknowledged flaws in the study design and recently issued new guidelines to address problems facing psychedelic drug researchers.

A number of other critics have spoken out in recent months, including from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a nonprofit that studies the costs and effectiveness of medicines, which issued a report questioning Lycos’ findings, calling the treatment’s effectiveness “inconclusive.”

Other groups, such as the American Psychiatric Association, have not outright opposed approval, but have urged the FDA to implement strict regulations, strict controls over prescribing and dispensing, and close patient monitoring to mitigate any potential adverse effects.

An FDA staff analysis recommended that approval should be contingent on restrictions in healthcare settings, patient monitoring, and thorough reporting of adverse events.

Just before voting on Tuesday, the advisory committee heard from more than 30 speakers who offered starkly different views on the application.

Some critics have focused on veteran psychedelic advocate Rick Doblin, who in 1986 founded the Interdisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Research, a nonprofit that submitted the first application for MDMA-assisted therapy to the FDA, and which later founded a for-profit organization that became Lycos earlier this year.

Brian Pace, a lecturer at Ohio State University, described the company, which is seeking licensing, as a “therapy cult” and criticized Doblin’s public comments highlighting his enthusiasm for psychedelics, including his belief that legalizing and regulating them would bring about world peace.

But the vast majority of those who spoke in support of the application shared very personal stories of how MDMA therapy had largely quelled their PTSD symptoms.

Among them was Christina Pierce, who said she suffered from PTSD after being sexually assaulted at age 9. She was prescribed a number of psychiatric medications over the years and at one point even attempted suicide.

MDMA therapy has changed her life, she says: “What once felt like a tsunami of overwhelming panic is now just a puddle at my feet,” says Pierce, who founded a group to help women recovering from trauma.

She ended her testimony by urging the FDA to approve the application.

“How many more people need to die before an effective treatment is approved?” she asked. “When considering the risks, keep in mind that this treatment could save many lives. I lost much of my life to this disease and am grateful to now have it back, but I wish this drug had been approved decades ago.”