PUBLISHED

August 03, 2025

In the region of Pakistani Punjab, particularly in urban centre’s such as Lahore, Sialkot, Sheikhupura, and Faisalabad, Christian hymnody has undergone a transformative process, emerging as a hybrid and multilingual artistic expression. This music serves as a mediator of memory, power, and resistance, reflecting the interplay of historical, linguistic, and technological shifts.

Originating from 19th-century colonial missions, this music has undergone a metamorphosis, bearing the imprints of British religious structures, vernacular adaptations, and the advent of digital expression. In contemporary Pakistan, worship music transcends its traditional role of accompanying liturgy. It assumes the roles of theological witness, cultural repository, and political voice.

Drawing upon Homi K. Bhabha’s concept of “Third Space,” theories of cultural memory, liturgical inculturation, and the burgeoning field of sonic theology, this article delves into the ongoing renegotiation of identity and place by Punjabi church music. From the rendition of Psalms in ragas to the creation of Instagram worship videos, this music has consistently reimagined its boundaries and positioned itself within a broader cultural context.

Following the British annexation of 1849, missionaries from Presbyterian, Anglican, and Methodist denominations commenced arriving in Punjab. Initially, prominent centre’s of mission activity were established in Ludhiana, Jalandhar, and Sialkot, where English hymnals and pipe organs were introduced into educational institutions and religious settings. By 1854, Ludhiana had emerged as a hub for Bible translation efforts, overseen by the American Presbyterian Mission. These missionaries introduced a European musical landscape characterised by rigid hymn structure, translated liturgy, and choral singing. Additionally, they introduced the harmonium, a portable reed organ manufactured in France, which became an integral component of worship.

The harmonium’s entry into India was facilitated by military regiments and Christian missionaries, initially appearing in northern cities such as Jalandhar and Ludhiana. Over time, it gained widespread popularity within rural Christian congregations due to its portability, affordability, and harmonious compatibility with Indian musical traditions. By the early 20th century, it had become an indispensable instrument not only for churches but also for Sikh, Hindu, and Sufi musical practices, often supplanting more delicate stringed instruments such as the sarangi and dilruba. This indigenization constituted a subtle act of cultural negotiation: the European instrument that once symbolised colonial distinction became a shared devotional medium across religious affiliations.

In 1904, the establishment of the Sialkot Convention further accelerated vernacular expression in worship. Organised by a coalition of foreign missionaries and local Protestant leaders, the Convention quickly became the most significant revivalist Christian gathering in colonial Punjab. Held annually in Sialkot, it featured preaching, collective Psalm singing, and teaching sessions in both Urdu and Punjabi. The Convention served as a liturgical counterpoint to Western ecclesiastical formalism, empowering Christians to explore faith in familiar languages and sounds. After Partition, it continued to shape Pakistani Protestant identity, embedding musical memory into spiritual revival.

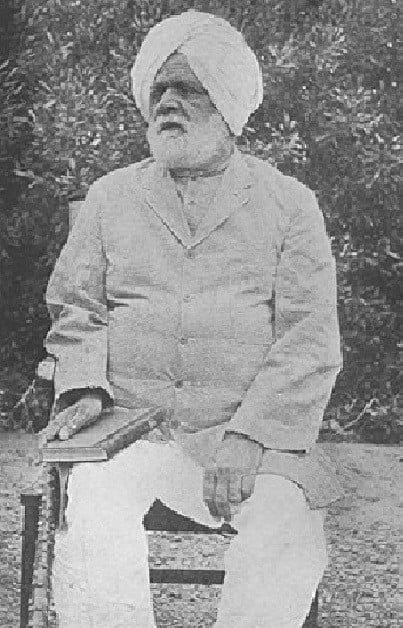

A pivotal moment in the creation of contextualised church music emerged from the work of Rev. Imam-ud-Din Shahbaz (1845–1921). A former Muslim convert and linguistic prodigy, Shahbaz rendered the entire Book of Psalms (Zaboor) into lyrical Punjabi verse between 1888 and 1905. These translations were composed in many ragas like kafi, pahari and bhairavi, melodic modes employed in Punjabi folk, Sufi, and classical traditions. Shahbaz’s Psalms transcended the role of mere theological texts; they were poetry imbued with rhyme, rhythm, and call-and-response structure.

In the kafi tradition accompanied by a harmonium, these Psalms resonated not only with Christians but also with the broader village soundscape. According to mission records from that era, villagers, including Muslims and Sikhs, were drawn to Shahbaz’s compositions. In Bhabha’s terminology, Shahbaz had established a Third Space: he reinterpreted colonial Scripture by integrating it into the core of Punjabi musical culture.

Even after Punjabi became the dominant language in the liturgical sphere, Urdu retained its position as the primary language of worship, particularly in urban settings. As the lingua franca of colonial administration and post-partition national discourse, Urdu facilitated the gathering of worshippers from diverse regions and dialects in a unified liturgy. Its theological versatility also contributed to fostering interfaith familiarity. Words such as “Allah” (God), “Ruh-ul-Quddus” (Holy Spirit), and “Masih” (Messiah) are shared across Islamic and Christian traditions, despite their divergent meanings.

According to liturgical scholars, Urdu provided a rich repository of poetic devices, drawing upon Arabic, Persian, and Turkic traditions. Hymns and Psalms composed in Urdu were frequently set to musaddas (six-line) or ghazal-style meters and accompanied by tabla-driven ragas. This fusion of scriptural depth and lyrical intimacy rendered Urdu hymns both accessible and spiritually resonant.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a second wave of vernacular creativity emerged, particularly within the Catholic Church. Inspired by the emphasis on liturgical inculturation outlined by Vatican II, missionaries in Pakistan embarked on the creation of Urdu-language hymnals that seamlessly integrated local musical traditions. Father Liberius Pieterse, a Dutch Franciscan stationed in Multan, published “Hamd-Ullah” in 1955 and later co-edited “Naya Geet Gao (Sing a New Song)” with poet Ghulam Masih Felix in 1972.

Parallelly, figures such as Father Exo-Pierre and Father Laborious Azad composed settings of the Kyrie and Gloria in Urdu, employing raag bhairavi phrasing and tabla rhythms. These hymns introduced melodic scales and rhythms that resonated deeply with the Pakistani audience, transforming the auditory experience of Mass and imbuing it with both sacredness and familiarity.

“Naya Geet Gao” swiftly transcended denominational boundaries, finding resonance with Protestant choirs as well. Its triumph underscored the transformative power of inculturated hymnody in uniting Pakistan’s fragmented Christian communities and conferring musical and theological significance upon worship.

While church music shared many characteristics with Sufi qawwalis and Hindu bhajans, such as harmonium accompaniment, tabla rhythms, and poetic metaphors, it retained a distinct theological structure. Church hymns typically followed SATB (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) harmonies or unison singing with call-and-response sections. In contrast, qawwalis relied on solo improvisation, and bhajans on antiphonal chants. Terminologically, church hymns emphasised concepts like “Yesu,” “Najat,” and “Salib,” while qawwalis focused on “Nabi,” “Wahdat,” and “Ishq-e-Haqiqi.”

It is also noteworthy that the call-and-response form in Christian music carries deeper psychological implications. This participatory structure has historically empowered congregants, particularly in rural and marginalised communities, to engage with Scripture not as passive listeners but as co-creators of worship. This is one reason why even today, the performance of the Zaboor continues to play a central role in village churches and revival meetings. Music, in these settings, becomes both a method of instruction and a mode of emotional healing.

From 2010 onward, Pakistani church music entered the algorithmic era. YouTube channels such as Hallelujah Band and Zaboor Studios commenced producing professionally recorded Urdu and Punjabi worship videos. These were often structured in the musical language of Hillsong-style global worship: guitar-driven praise, layered harmonies, and emotionally charged choruses. However, unlike global megachurch music, these productions retained tabla, dholak, and folk instrumentation.

One of Hallelujah Band’s most viewed tracks, “Rab Janay,” commences with a bhangra beat and transitions into an English hook: “You know my heart.” This musical code-switching reflects a broader diasporic sensibility: young Christians singing to both God and algorithm, to both local community and global audience.

Church music has long served as a form of spiritual resistance in Pakistan. Following the 2013 bombing at All Saints Church in Peshawar, mourners gathered amidst the rubble to sing Psalm 23 in Urdu. The footage, captured on mobile phones, gained widespread attention and became a symbol of national unity. In 2015, when suicide bombers targeted Catholic and Protestant churches in Lahore’s Yohannaabad neighbourhood, youth choirs responded by singing through the streets, demonstrating their resilience and determination.

In response to the Joseph Colony arson in 2013, which resulted in the destruction of over 150 homes, churches held overnight Zaboor recitations using harmoniums and candles. Following the Jaranwala church burnings in 2023, where 26 churches were torched, worshippers returned to sing Psalm 91 amidst the ashes, invoking divine protection. In Sargodha in 2024, after a mob attack on a Christian household, survivors gathered in homes to chant Zaboor in whispers, resisting erasure through sacred sound.

Theologians and musicians argue that these acts exemplify monumental memory: the preservation of suffering and hope through sound. Church music not only commemorates trauma but also reclaims space. In a sonic-theological perspective, lament transforms into protest through praise.

Simultaneously, in the diaspora, from Toronto and Dubai to Birmingham and Melbourne, Punjabi Christians continue to practice their faith in three languages, spanning across four time zones. Diaspora churches harmoniously blend Shahbaz’s Punjabi Psalms with Hillsong choruses, disseminate Sunday services on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, and creatively remix Naya Geet Gao classics into electronic dance music (EDM) sets for youth conferences. This transnational musical fusion transcends geographical boundaries, fostering a vibrant and postcolonial liturgical community that is both multilingual and distinctly alive.

Numerous Pakistani renowned musicians, including S.B. John, Saleem Raza, and A. Nayyar, initially received training in church choirs. Their contributions to Lollywood film music incorporated elements of gospel phrasing, harmonic layering, and spiritual lyricism. Presently, programmes like Coke Studio Pakistan continue this crossover legacy. For instance, Hadia Hashmi’s rendition of “Bol Hu” draws upon Christian vocal stylings and melodic structures prevalent in Urdu worship.

In Pakistani Punjab, church music serves not merely as a liturgical embellishment. It constitutes a space where colonial form intersects with local expression, where Scripture is sung in folk metre, and where faith persists despite adversity. Whether through kirtan-like harmonium chants or digital mashups incorporating English refrains, this music embodies a theology that undergoes constant reimagination through resistance, sound, and community.

Church music plays a pivotal role in interfaith dialogue and public memory. In various regions of Punjab, Christian worship groups are invited to perform at civic festivals or university gatherings, particularly during Christmas or interfaith harmony week. These performances, often delivered in Punjabi and Urdu, underscore the shared aesthetic and emotional language of religious music across Pakistan’s diverse communities. When Zaboor is performed in a setting that also includes Sufi qawwalis or Sikh shabads, it not only demonstrates musical convergence but also fosters mutual respect. In such moments, sacred sound becomes a connecting bridge between traditions through emotion, narrative, and reverence.

Another aspect worthy of note is the role of female voices in church music, which is often underrepresented in formal liturgical settings. Over the past decade, more Christian women have emerged as soloists, worship leaders, and composers. In choirs from Youhanabad to Gujranwala, female vocalists now lead Psalms in congregations and livestream performances. Their presence adds novel textures to sacred music and challenges traditional gender hierarchies within ecclesial spaces.

Furthermore, youth-led worship collectives such as The Worship Project Pakistan and Rising Faith Ministries have commenced organising open-air concerts and praise nights, particularly during Easter and Christmas. These gatherings often combine classical Zaboor settings with contemporary genres such as pop-rock, acoustic folk, and even spoken word poetry. By merging tradition with experimentation, young Christians ensure that church music remains a pertinent and evolving expression of faith.

Lastly, education initiatives surrounding music literacy are gaining traction. Institutions like Forman Christian College in Lahore and St. Thomas Seminary in Karachi now provide formal training in church music, composition, and theology. Through workshops, certificate programs, and performance ensembles, a new generation of trained liturgists and composers emerges equipped not only with musical proficiency but also with a profound understanding of their heritage.

Church music in Pakistani Punjab encapsulates the intricate and multifaceted identity of a post-colonial nation: multilingual, devotional, politically aware, and profoundly resilient. Drawing inspiration from Bhabha’s concept of hybridity, it seamlessly integrates Western liturgical practices with Punjabi emotional expressions. Through cultural memory, it effectively resists the erosion of historical recollections; through inculturation, it maintains its strong connection to its cultural roots; and through sonic theology, it effectively communicates without the need for verbal articulation. As Christian communities persistently face marginalisation, their music continues to serve as a poignant soundtrack of survival, embodying a theology not merely spoken but also manifested through the act of singing.

Brian Bassanio Paul is a music enthusiast whose expertise lies at the intersection of music business, artist development, music appreciation, and cultural studies.

He can be reached at brian.bassanio@gmail.com and on LinkedIn @brianbassanio

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author