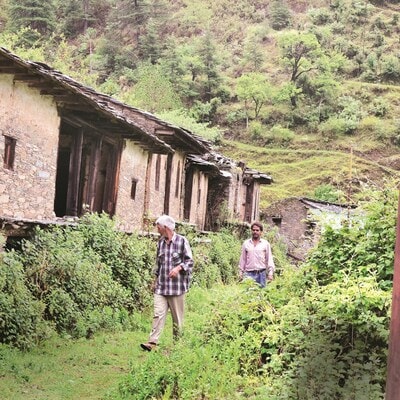

An eerie silence hangs in the mountain air as the sun’s golden rays filter through the giant cedar trees of the Himalayas, casting a warm glow on the valleys and villages below. Echoes of the past reverberate through the abandoned and crumbling houses that form the eerie remains of a vanished existence in what have come to be called Uttarakhand’s “ghost villages.”

The severity of the problem is underscored by the fact that 24 villages in the state did not have a single polling station in the recent Lok Sabha elections, the first time such a move has been made since India began electoral rule, and the state migration commission classified them as “uninhabited villages” from 2018 to 2022.

Click here to connect with us on WhatsApp

These villages are located in Almora, Tehri, Champawat, Pauri Garhwal, Pithoragarh and Chamoli districts. Incidentally, Almora had the lowest voter turnout among the five Assembly seats in the state.

This is not a new phenomenon in Uttarakhand, where the number of “ghost villages” is on the rise. Across the state, a staggering 1,048 villages lie deserted and deserted, with a further 44 villages barely surviving with fewer than 10 residents, according to the latest 2011 census. This mass displacement has left an indelible mark on the region’s economic and cultural fabric, a solemn reminder of the fragility of a way of life that has lasted for generations.

Films like Pandavas Productions’ Yakuran capture the deep loneliness and nostalgia felt by the few remaining residents, with its aging protagonist conversing with himself, his cows and stray animals, and the melancholic strains of folk songs echoing through the deserted streets.

As the filmmakers say, “Yakrans” portrays a liberal and progressive perspective, but at the same time it is full of nostalgia, encapsulating the bittersweet essence of a way of life that hangs in a precarious balance and whose future is uncertain.

“People have stopped farming and the village has turned into a jungle,” laments Rajeshwari Bhandari, former village head of Mishni Gaon in Pauri district.

Another resident, Devi (who only gives her first name), once donated her land for a hospital but now watches helplessly as residents are forced to travel as far as Srinagar for treatment because the hospital lacks essential services such as X-ray and ultrasound machines.

Migration

The root cause of village migration is a lack of economic opportunities.

“We have not invested in employment-intensive sectors, which has sapped the aspirations of the youth,” laments Rajendra Prasad Mangain, an economist at Doon University.

Agriculture, the traditional industry in these villages, is declining due to low productivity, land scarcity and fragmented land ownership. “Farmland is being overrun by monkeys and other animals,” said Jagat Singh Rawat, a former school principal in Dwarikal district of Pauri Garhwal.

Lacking stable employment, young people are fleeing to cities and towns in search of better prospects. “People are leaving the land, taking their wives and children,” Rawat said, highlighting the gravity of the displacement, which has left entire villages without livelihoods and homes and fields in ruins.

The impact on education is equally dire. “In some colleges, there are more teachers than students, which creates a demotivating environment,” says Tajvar Singh Negi, a serviceman from Pauri Garhwal’s Liknikal area.

Mamgain says the economic losses associated with these “ghost villages” have been largely unquantified: “There are no large-scale studies estimating the economic losses.”

However, the consequences are evident in declining property values and indigenous peoples’ unwillingness to sell their ancestral lands.

“Aboriginal people cannot make a profit from selling land,” Mamgain said. “On average, households own very little land – over 80 percent of the population own less than two acres, and it is very dispersed.”

The Rural Development and Migration Commission was established in 2017 to address the issue. But the migration wave continues unabated.”[There is] “There is no holistic approach and no strong coordination between sectors,” he said, calling for a comprehensive strategy that integrates job creation, infrastructure development and policy reform.

Mamgain is involved in the Hill Policy, which was launched under former Uttarakhand chief minister BC Khanduri to focus on small and medium enterprises in the region. But there are problems.

Mamgain says that in the name of industry, they are mainly focused on solar energy. “We are just occupying barren hills for profit,” he says, stressing that local people are not employed to service these plants. “Most of the mechanics come from Madhya Pradesh and Bihar.”

Scholar and food historian Pushpesh Pant cites several interrelated factors that caused migration from villages in Uttarakhand: environmental disasters that caused “subsidence” in places like Garbyan on the Indo-Tibet border in the 1950s, the collapse of traditional livelihoods such as cross-border trade when “Indo-Tibetan trade came to a halt” after the 1962 Sino-Indian war and “these villages lost their livelihoods,” a lack of economic opportunities for young people to seek work or education elsewhere, and reservation benefits that encouraged migration from villages.

Pant expressed serious concerns that “mindless” tourism development will destroy the fragile ecosystem and lead to crude commercialisation rather than genuine preservation of culture.

He laments that Munsiyari, home to the Bhotiya people of the Johar Valley, has been transformed from “a place of pristine, unspoiled and incredible natural beauty into a commercialised place where people go to eat momos and thukpa”.

While noting the alienation of the younger generation from their cultural roots, Pant also warned against forcing people to return when they have “no livelihoods, no healthcare, no schooling, and even no housing.”

Why the hills have gone quiet

| Reasons for migration (%) | |

| Livelihood or unemployment issues | 50.16 |

| Lack of medical facilities | 8.83 |

| Lack of educational facilities | 15.21 |

| Lack of infrastructure (roads, water, electricity, etc.) | 3.74 |

| Lack of productivity and yields on farmland | 5.44 |

| Migration due to the influence of family and relatives | 2.52 |

| Damage to agriculture caused by wild animals | 5.61 |

| Other important reasons | 8.48 |

Source: Interim Report on Migration Situation in Gram Panchayats of Uttarakhand, Migration Commission (April 2018)