The world’s oceans have been breaking daily temperature records continuously since the beginning of 2023, a year-long heatwave that has worried and disheartened climate scientists, coral reef experts and even hurricane forecasters.

In the key areas of the Atlantic where hurricanes form, water temperatures are “really astonishing,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior scientist who studies hurricanes at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Management.

Warmer ocean waters and sea surface temperatures are like an octane boost during hurricane season, providing more fuel that drives the development and intensity of hurricanes and tropical storms moving across the ocean. Warmer than normal waters in the Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico play a starring role in all seasonal outlooks for the Atlantic hurricane season, which begins June 1.

“The entire tropical Atlantic is experiencing its warmest temperatures so far for this time of year,” McNoldy told USA Today on Thursday, temperatures not typically seen until mid-August. And “the Caribbean is in an uproar.”

The daily average temperature record in the Atlantic north of the equator was broken for just four days in April and May, when the average water temperature during that period fell to just 0.1 degrees Celsius below last year’s record.

“And all of this is happening on the heels of 2023 being the warmest on record for this time of year,” McNoldy said. “We’re now breaking the 2023 record, so that’s not a good thing.”

During last year’s hurricane season, record-warm ocean temperatures likely suppressed at least some of the potential hurricane activity due to vertical wind shear over the Atlantic Ocean caused by El Niño wind shifts in the Pacific.

Still, this season has been more active than normal, producing seven hurricanes and 20 named storms, making it the fourth-most active season on record. This year, that protection is gone as the weather pattern shifts toward La Niña, potentially reducing wind shear over the Atlantic, and seasonal hurricane forecasters fear the worst.

Warmer waters are also thought to have contributed to widespread bleaching of coral reefs around the world, and to the rise of foul-smelling sargassum that covers beaches, harmful algae blooms and mass fish kills. Experts also say warmer waters in the Gulf of Mexico have made more water available for storms, contributing to increased tornado activity this spring.

How hot is the sea?

Global average sea surface temperatures appear to have recently dropped a little more rapidly than normal for this time of year when both hemispheres are in seasonal transition, but they are still the warmest average temperature on record for this date.

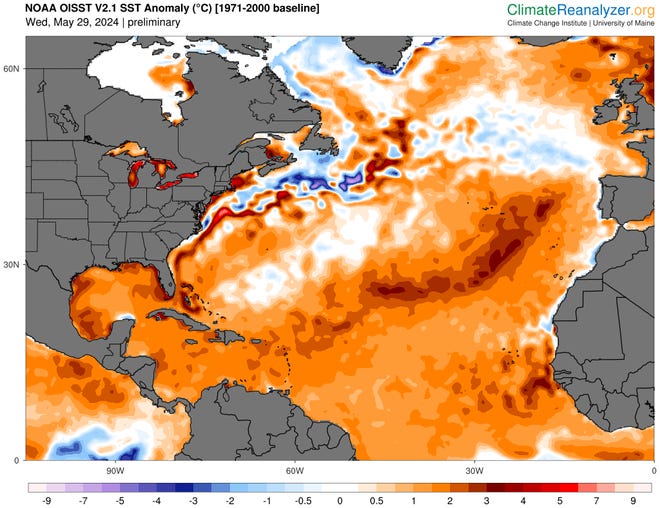

The average temperature in the North Atlantic on Thursday was 72.14 degrees, 2.34 degrees warmer than the 1982-2011 average, according to the University of Maine Climate Change Institute’s Climate Reanalysis Instrument, which uses NOAA data.

According to Phil Klotzbach, senior research scientist and seasonal forecast team leader at Colorado State University, the average May water temperature in the Atlantic Ocean between latitudes 10 and 20 degrees, where tropical cyclones usually form, is nearly 1 degree warmer than any year since records began in 1982. That’s 2.52 degrees warmer than the 1991 to 2020 average.

Hot oceans cause problems for hurricane season

Organizations including Colorado State University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration say warming waters are a key factor in forecasting seasonal hurricanes, which is one reason their forecasts now include more storms than ever before.

“Record-high sea surface temperatures alone do not guarantee a busy hurricane season, but they certainly will have a strong impact,” Michael Lowry, a hurricane expert for WPLG Local 10 in Miami, wrote in a column for Yale Climate Connections.

Warm water provides fuel for hurricanes, encouraging an influx of heat and moisture that rises into the air and helps form the giant cloud structures that form and intensify hurricanes.

For example, warmer than normal waters in the Gulf of Mexico are believed to intensify storms like Hurricane Katrina. Warmer water is thought to increase the intensity of heavy rainfall in storms like Hurricane Harvey and cause rapid intensification, such as the sudden intensification of Hurricane Idalia before making landfall on Florida’s Gulf coast last year.

When wind shear is low and water temperatures are warm, there is little to stop the cloud structures that form from gaining strength and intensity. Conversely, as a hurricane moves northward over the cooler waters of the Atlantic, it begins to lose strength.

Why is the Atlantic Ocean so hot, and how long will it last?

Scientists aren’t sure why the rise in average ocean temperatures has been so persistent — at least for now, there’s no clear explanation, McNoldy said, and he doesn’t expect one to emerge anytime soon.

Scientists believe most of the warming is due to heat absorbed by the oceans from increased human-made fossil fuel emissions, but other factors could also be at play, including El Niño weather, improving air quality, and even an influx of moisture from the eruption of the Hunga Tonga volcano in early 2022.

Klotzbach told USA Today that weak trade winds over the past few months have contributed to warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic hurricane belt.

Klotzbach said that even if the region warms at the slowest rate on record between now and September, it would still be the second-warmest September in the region after 2023. Based on NOAA records available since 1981, the region would still be 0.54 degrees warmer than the top six years (2020, 2010, 2005 and 2017).

“There is no reason to expect the warm water anomaly will disappear or return to normal” as summer approaches, McNoldy said.

“That’s unlikely,” he said.

It’s too early to tell whether the Atlantic heat will continue to beat the 2023 record or fall below it, but McNoldy said there’s plenty of room to fall below the 2023 record and still “beat any other year.”

When the peak of hurricane season begins in July and August, water temperatures will typically reach their highest, plus unusually high temperatures, “not only will the hurricanes intensify,” he said, “and then we have to worry about the remaining corals dying off.”

Water temperatures at some stations in the Florida Keys and Everglades National Park have already reached 90 degrees.

Dinah Voyles Pulver covers climate and the environment for USA TODAY. She can be reached at dpulver@gannett.com or @dinahvp.