Sonny Vaccaro knew nothing about the law, but he knew a lot about college sports and was convinced that the players who brought in millions of dollars in revenue for their universities should be paid.

Michael Hausfeld knew nothing about college sports, but it didn’t take long for the lawyer who built his reputation challenging oil companies and Swiss banks to conclude that the NCAA’s business practices were illegal.

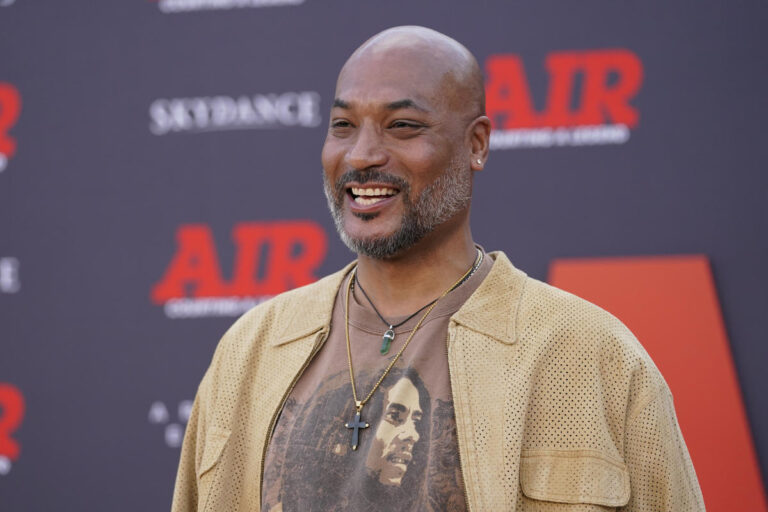

“I went up to him and said, ‘I think these players are being treated badly,'” said Vaccaro, the former sports executive best known for helping Michael Jordan sign with Nike out of college. “And then Hausfeld said something I hadn’t even thought of: ‘Okay, now find me someone who’s going to sue.'” He said that.

Searching for a catalyst to challenge a system they believed was unfair to college athletes, Vaccaro and Hausfeld found it in Ed O’Bannon, the former All-American basketball player and MVP of UCLA’s 1995 national championship team. O’Bannon signed on as lead plaintiff in a 2009 lawsuit alleging that his image had appeared in a popular NCAA-sanctioned video game by EA Sports without compensation.

O’Bannon challenged the NCAA’s right to profit from the use of players’ names, images and likenesses in an antitrust lawsuit filed by plaintiffs including Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell, and Vaccaro was present when they won the case in 2014.

“I just wanted to right a wrong,” O’Bannon said at the time.

The game disappeared because EA Sports didn’t want to take any more legal risks, but after a decade-long hiatus, the college football version of the game is back with a bang: EA Sports says more than 2.2 million people were playing College Football 25 even before its official public release last week.

The players who will play in the games are clearly identified and paid.

Impact of the O’Bannon Affair

A decade after that ruling, the NCAA’s longstanding collegiate-amateur model is all but gone, with the association and the five major conferences agreeing to a $2.8 billion antitrust settlement in May that included a plan to share revenue with players.

While it’s a coincidence that the settlement announcement and EA Sports’ return occurred within weeks of each other, the symbolism couldn’t be more appropriate.

“We knew from the beginning that we were going to be challenging the NCAA’s disguised notion of amateurism,” Hausfeld told The Associated Press.

O’Bannon’s complaint was born after he noticed an unnamed avatar in a UCLA uniform looking and playing a lot like him while playing EA’s college basketball game. Lawsuits filed in his name have made him a figurehead for the downfall of the NCAA and the exposure of college sports as a billion-dollar industry run by unpaid labor.

It’s not a legacy O’Bannon is embracing, and he declined an interview request from The Associated Press.

“I knew I had to do something,” he told Sportico in May. “I thought once people started looking into the NCAA rules, they’d realize they were really weird. Video game companies are paying NBA and NFL players, so why can’t they pay college athletes to be in video games? It just doesn’t make sense.”

Building the Case

College football players also played a role. When quarterback Sam Keller transferred from Arizona State to the University of Nebraska, he noticed that his video game avatar also appeared to have changed schools. Keller filed his lawsuit a few months before O’Bannon.

Hagens Berman attorney Robert Carey said it was former University of Michigan football player Chris Horn who first alerted him to the video game’s use of players’ likenesses without permission. Carey and his colleagues investigated the details and determined that a class-action lawsuit was possible.

“We spent a ton of time matching up the (real-life) rosters to the (video game) rosters, and we did it with the understanding that the height had to be within an inch, the weight had to be within X percent so that we could weed out anyone who didn’t match, because there were people who didn’t match,” Carey said. “It was a lot of work.”

Carey said he quickly realized the case would be about more than just video games, and he said the law firm was wary of taking on the beloved business of the NCAA and American college sports.

“The NCAA wasn’t some little litigation lawyer. They fought tooth and nail with powerful law firms, high-paying lawyers, highly paid lawyers,” Carey said.

Keller’s lawsuit seeks damages for players whose images have been used at games over the years, a departure from O’Bannon’s approach in challenging NCAA rules that prohibit compensation to players.

“This was a property theft case,” Carey said. “Theirs was a market restraint case.”

The two lawsuits were consolidated, but the Keller lawsuit was eventually settled for $20 million. O’Bannon’s team continued the litigation, and U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken of the Northern District of California found no sentiment in favor of maintaining the status quo in college sports.

“She got it. She got the arguments the NCAA was trying to make and she shut down almost all of their defenses about amateurism,” said John Solomon, a reporter who covered the trial at the time and is now with the Aspen Institute’s Sport & Society Program.

Judge Wilken ruled against the NCAA on August 8, 2014. It took a year for an appeals court to uphold the decision, and another six months for the Supreme Court to issue a decision to dismiss the case.

aftermath

The NCAA positioned the decision at the time as a battle lost but not a war lost. These interpretations, along with the slow pace of the legal system, seemed to obscure the severity of the decision from public perception.

Those closest to him realized that a significant domino had occurred.

“I knew there would be a payoff eventually,” Solomon said.

Only in 2021 did the NCAA lift its ban on athletes earning celebrity money. Thousands of athletes are now making millions in endorsement deals, big and small. But while NIL has become something of a substitute for an athlete’s salary, more antitrust lawsuits have arisen and a 2021 Supreme Court decision stripped college sports of virtually all defenses, making it clear that athlete pay is here to stay.

Finally, the NCAA and college sports leaders have backed down: College athletes will get a cut of the billions of dollars in revenue that sports generate as early as 2025, fearing another legal defeat could bankrupt the sports industry.

“It’s over. The game is over,” Vaccaro said of NCAA amateurism.

Ironically, for many, the game has returned better than ever.

____

Follow Ralph D. Russo https://twitter.com/ralphDrussoAP

____

AP College Football: https://apnews.com/hub/college-football