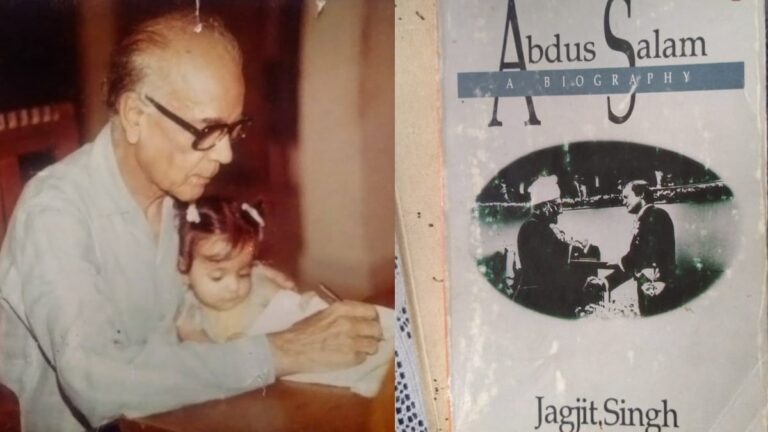

Dr Jagjit Singh with his granddaughter Shalini Singh (left), the book cover of the biography he wrote on Pakistan’s first Nobel Prize winner Abdus Salam (right). Image Courtesy: Shalini Singh

In parts

one

and

two

of the Salam Series, we took a deep dive into the life of Pakistan’s first Nobel laureate Prof. Abdus Salam. While Salam’s son, Mr Ahmad Salam narrated the brilliance of his father and how Pakistan relegated him to the side because he was an Ahmadiyya, Pakistani scientist and author Prof. Hoodbhoy unravelled the deeper issue in the country, i.e. how Islamabad prioritised religion over building a strong educational and scientific foundation.

Part three of the series was not on the cards until Ms Shalini Singh gave insights into the fascinating life of her grandfather. Shalini, a journalist and co-founder of the People’s Archive of Rural India, reached out to Firstpost after reading our series and revealed that her paternal grandfather, Dr Jagjit Singh, had not only been India’s top science writer but was also trusted by Salam to write his biography.

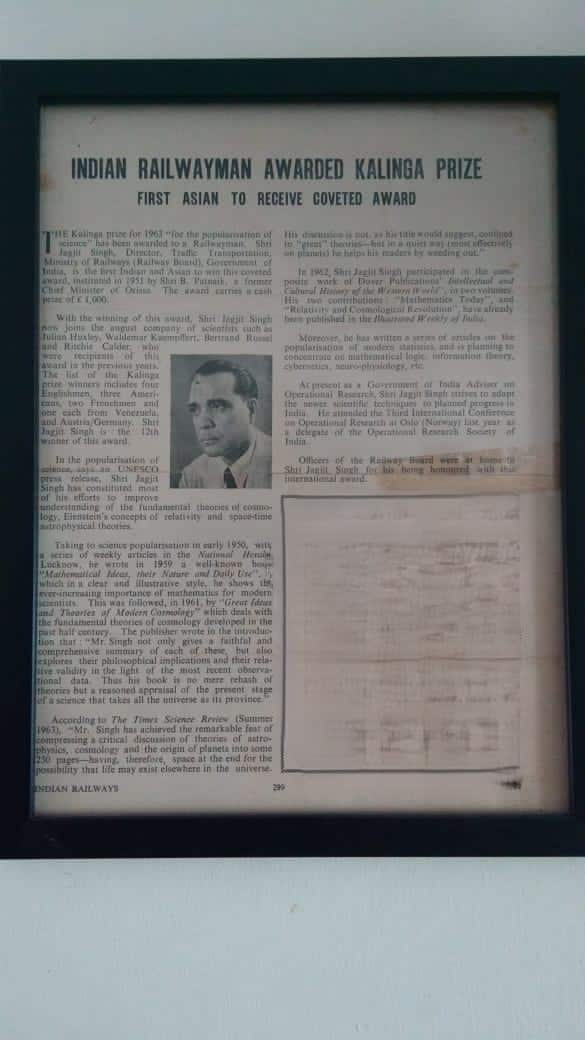

The biography in question came out in the year 1992 and was published by Penguin Books. But there is more to Singh’s story. As Shalini describes him perfectly, Dr Singh was “a mathematician by education, public administrator / ‘railway-man’ by profession and a science populariser by passion.” His love for science, logic and reasoning made him the first Asian to win UNESCO’s Kalinga Award for science popularisation in 1963. It’s the oldest prize instituted in 1951 and won by people such as Bertrand Russell, Julian Huxley etc.

For the purpose of the story, Shalini took some help from Singh’s autobiography “Reminiscences of a Mathematician Manqué,” to substantiate her assertions.

Let’s take a look at the life of Dr Jagjit Singh and see why Pakistan’s first Nobel laureate chose a science writer or rather a ‘science populariser’ to write his story.

Who was Dr Jagjit Singh?: Mathematician, railwayman and a science populariser

Dr Singh was born in 1912 in Amritsar. He completed his MA in Mathematics from Government College in Lahore back in 1933 and eventually came to contribute significantly to putting a young, post-independence India on the global scientific map.

While professionally he was a man of Indian railways, he wrote multiple books on mathematics, cosmology (a branch of astronomy that deals with the evolution of the universe), and operations research (using mathematical analysis for problem-solving), most of which were translated into several foreign languages.

During the interview, Shalini mentioned that many of his books were bestsellers and his work was celebrated all around the world. “Till date, we receive a royalty for his book, ‘Genetics Today’, available in Hindi and English, from the National Book Trust of India,” she remarked. As a science populariser, success for Singh first came when his first book titled ‘Mathematical Ideas’ garnered laurels worldwide.

The first draft of the book which was released in the 1950s was called ‘Mathematics and You’. The book was rejected by Penguin due to a perceived ideological difference and was published by Hutchinson Group, London and Dover Publications, New York, with the changed name. Right off the bat, the book received rave reviews.

“There ought to be a law that every teacher of mathematics in our secondary schools, technical colleges and universities should read this book and not be allowed to teach his subject until he passes an examination in its contents,” wrote Belgian physicist L. Rosenhead. Not only this, the book which also aimed at providing people with high school knowledge of mathematics, an understanding of mathematical ideas used in sciences of modern civilisation, became a “bedside read” for India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Shalini noted that throughout his career, Singh applied a “scientific approach to his public sector work in India, setting a pragmatic example of a philosophical ideal.” But before we dive into Singh’s life, let’s look at his association with the legendary theoretical physicist Abdus Salam.

Singh and Salam: An association that went beyond borders

In the prologue of Salam’s biography titled ‘Abdus Salam, A Biography,’ Singh elucidated the chain of events that led Salam to choose him to be his biographer. “My sole qualification is that I had written, over a decade ago, a short piece popularizing his new theory unifying two of the four fundamental forces of nature, a feat as seminal now as James Maxwell’s unification of electric and magnetic forces over a century ago. Since then I have had the honour and happiness of receiving from him, material for writing his biography,” Singh wrote while introducing the book.

“As I have had a long-simmering admiration for the meteoric rise of a fellow countryman of the Indian sub-continent to the zenith of the firmament of world science, I have undertaken a task he has chosen to forswear,” he added.

Both Salam and Singh belonged to the orbit of scientists who believed that scientific collaboration between India and Pakistan was only possible if both countries improved their turbulent relations. “In 1978, the late economist Tarlok Singh, who was a member of the Planning Commission of India since its inception invited my grandad to join him to carry out a series of studies for cooperation in development in South Asia – India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka,” Shalini explained.

Before the 1978 meeting, Singh recalled that such efforts were spearheaded by Abdus Salam and the Father of the Indian Nuclear Program, Homi Jehangir Bhabha, in the 1960s.

“Prominent scientists and scholars in both countries, as, Dr HJ Bhabha, chairman of the Indian Atomic Energy Commission, and Abdus Salam, chief scientific advisor to Pakistan, had realised that neither country could afford the massive investments required to implement its plans of economic development and rejuvenation of science without halting their ongoing conflict,” Singh wrote in his autobiography. “Bhabha and Salam tried in the early 1960s to implement the Pugwash appeal for world disarmament in so far as their own countries were concerned. But they failed to arrange a meeting between Nehru and General Ayub Khan to find ways of resolving the long-simmering conflict between the two countries by peaceful means,” he furthered.

Mathematician: How Singh didn’t get to be a professor at his college in Lahore

As mentioned before, Singh wore many hats over the years. He was a mathematician, public administrator and a science populariser. However, there were several turns of events that contributed to the making of the renowned science writer. Shalini recalled that her grandfather wanted to be a mathematician. “He won all the academic distinctions, scholarships, and medals that are the normal rewards of doing well in university examinations,” Shalini told Firstpost, quoting from his autobiography

“This led him to believe that as soon as he ‘got off the college hook’ by passing the last examination, the principal of his college, the famous historian, HLO Garrett, would employ him as a member of his mathematics faculty in the ‘prestigious Government College, Lahore’. When after a long enough wait no such offer came, Singh took the Public Service Commission,” she added.

Interestingly, Salam graduated from the Government College of Lahore and joined the mathematical department as a professor after he returned from Cambridge.

Singh: The science populariser

While the prestigious Kalinga Prize solidified his legacy as one of the world’s renowned science writers, Singh’s passion brought him in contact with great minds who provided a structural foundation for the development of science in India. Between 1960-1965, Singh did a series (later compiled into a book) called ‘Eminent Indian Scientists’ for The Illustrated Weekly.

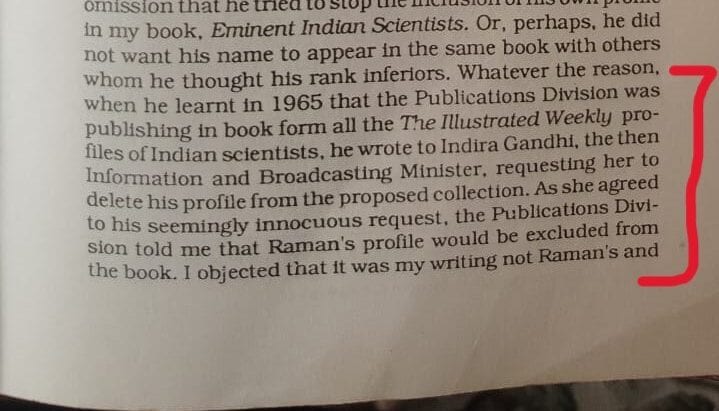

These works led him to be touted as a science populariser in India and his reputation reached the world. While writing about Indian scientists, some of his interactions were not as awe-inspiring as one might imagine. Shalini mentioned that Singh’s series, ‘Eminent Indian Scientists’, kicked off with a profile of CV Raman, India’s only science Nobel laureate.

However, in his book, Singh recalled his irreverent exchange of words with Raman, who did not like the fact that he was being put in the “same league” as other Indian scientists. “What motivated you to write that piece? If it was to make me and my work better known, there was no point in writing it as I am already so famous,” Singh quoted Raman in his book, saying this to him when they met in Bangalore four years later. Singh offered to write another piece reviewing his new work, however, the opportunity didn’t fructify.

In his autobiography, Singh said that Raman wrote to then-I&B Minister Indira Gandhi to get his profile removed from the compiled book with the same title as his IW column. Despite all odds, Raman’s profile is still featured in the book. However, not all interactions between Singh and Indian luminaries went downhill.

In the Firstpost interview, Shalini also recalled her grandfather’s brief but poignant interaction with Homi Bhabha. In his autobiography, Singh mentioned that when Bhabha’s profile was published in this series, through a cable exchange, the Indian physicist requested Singh to “tone down his praise” whilst comparing him with his friend, Robert Oppenheimer, the American theoretical physicist who was the subject of a Christopher Nolan film last year.

Singh looked forward to meeting Bhabha after this exchange but the legendary mind died in a plane crash a few months later. “For some mysterious reason, not finding anyone else, All India Radio managed to track down Singh to record a funeral panegyric on Bhabha,” Shalini shared from the chapter in his autobiography titled, ‘Bombay, Bhabha and Nehru’.

The Railwayman

Singh’s journey with the Indian railways can be mapped out by looking at his work in the pre-partition and post-partition era:

Referring to what Singh wrote in his autobiography, Shalini mentioned that Singh felt pre-partition India was too big to be evacuated by the British in one stroke. He pointed out that “one of the consequences of the partition was the sudden disruption of rail communications with our North-East region which includes border areas such as Assam, Tripura, Nagaland and North Bengal.” After the partition, most of the railway networks that connected the North-East region to the whole of India fell within the boundaries of Pakistan.

To restore the disrupted rail communications with the northeast region, bridge engineer Karnail Singh built the famous Assam rail link in the early 1950s. However, the capacity of this rail link remained an issue. A problem, which was eventually solved by Singh using algebra amid the 1965 Indo-Pak war.

- Post-Partition era: Singh found solution amid war

Singh was with the Indian Railways from 1936 to 1969. To elucidate his contribution to the railways during the Indo-Pak war, Shalini quoted the then-Vice Chancellor of Roorkee University who awarded him an honorary degree of Doctor of Science.

The vice chancellor’s citation at the award ceremony was: “In the wake of the Indo-Pak hostilities in September 1965 and closure of the supply to West Bengal, Assam, NEFA, Tripura and Nagaland via the river route through Pakistan, he increased the capacity of the N.E.F Railway all the way from Katihar / Siliguri to Dibrugarh / Badarpur by about 40% almost overnight – a unique performance indeed.” From 1960-1965 Singh served as the Director of the Indian Railway Board and came to be known as the ‘founding father of operations research’ in India.

A visionary mind

- As a public administrator

While recalling his takeaway from a 1968 meeting convened by former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Singh gave some thought-provoking insights. The meeting was about amendments to the science policy resolution. Singh realised that he neither fit in as a ‘scientist’ nor a ‘generalist’ in that group. However, he noted that “proficiency in science did not guarantee success in public administration.”

The second was the fact that “no skills can be codified in textbooks”. Singh believed that a good public administrator has to become a “machine that transforms decisions using two-way messaging between science and society.” Because of his contributions, Singh was asked to review the Union Public Service Commission syllabus in 1984.

As a science enthusiast, Singh had an extraordinary vision. In 1977, he was called by the University of Texas, Austin, to advise on how to popularise science among graduate students of the Humanities. During his visit, Singh met several celebrated international scientists including a young Indian, Swadesh M Mahajan, “who wanted to teach and research at home (India) but had to migrate abroad in the absence of an exciting scientific environment where high-quality teaching and research can flourish.”

Recalling the meeting, Singh emphasised that any country will grow scientifically if it comes out of the shackles of “yes-men”. “These people must compete as well as cooperate, create, and criticise, learn from one another, and establish a community of equals where the authority is a novel idea, not an Aristotle or Caesar. For science to flourish in India, nothing short of a fundamental restructuring of our institutions is needed,” Singh said in his autobiography.

It would have been interesting to know how Singh would have perceived India’s recent growth as a scientific powerhouse in the Space and IT sectors.

As a grandfather

Recalling Singh’s journey, Shalini gave an insight into his life as a ‘family man’. “A man born in small-town India, when the country’s literacy rate was less than 10 per cent, came to evolve gender dynamics in his family. I look up to him as someone who was a feminist and a chivalrous man – a rare combination in men not just back then but even today,” Shalini exclaimed.

“At a serendipitous meeting with celebrated economist and Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen at Harvard University during my Nieman fellowship year in 2017, he recalled Singh as “an agreeable man, of considerable intellect, and way ahead of his time” and that he’d read and kept several of his books,” she said.

‘Salam-Singh Grandkids’: How a story rekindles old ties

Shalini mentioned that she was in touch with Salam’s grandson, Saif, and said they had a WhatsApp group named ‘Salam-Singh Grandkids’. When asked how she got connected, Shalini narrated a fascinating story. “The way the Google algorithm led me to your first story on Abdus Salam two weeks ago, it was a social media hashtag that led me to Abdus Salam’s grandson five years ago! In October 2019, Netflix released a documentary on him. I was excited because my grandad had written his biography and this rekindled personal memories of him travelling to Italy in the late 80s – early 90s,” she said.

“So, I put out a post on my Instagram about this using one of the hashtags as #abdussalam … Incidentally, his grandson, Saif, who lives in California came upon it and wrote to me! We were so excited to learn of each other’s existence, given our grandfathers’ history that we quickly formed a WhatsApp group including his mother Aziza (Salam’s daughter),” she added.

Shalini mentioned that both of their lives got busy and over time they lost touch. However, it was this series that compelled Shalini to reach out to Saif once again. She shared the link to the series and told him about it.

When Shalini shared the news that she spoke to Salam’s grandson after ages and that the series has a big role to play in it, I must admit that it was the most heartwarming thing that could have ever happened to me as a journalist.

This is the third story in the three-part series. Click the following links to read the first two parts.

Find us on YouTube

Subscribe