The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to prevent cervical cancer will be rolled out from September 15 in Sindh, with health officials warning that community mistrust, persistent rumours and gaps in vaccinator training could undermine the campaign.

Around 50% of the target group is enrolled in schools, with coordination underway [between health officials and the] education department to facilitate in-school vaccinations, said Dr Rehan Baloch, speaking at the Globe HPV Seminar at Aga Khan Univeristy (AKU).

“We have earmarked around Rs 200 million for the HPV vaccine, with additional support from Gavi and other partners for advocacy and outreach,” he said, stressing the need for stronger engagement with parents, teachers and healthcare providers.

The campaign will rely on paediatricians, gynaecologists and frontline workers to inform communities about HPV and cervical cancer prevention.

Photo Courtesy: AKU

Sindh Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) Project Director Dr Raj Kumar described the rollout as a “historic initiative” and said preparations were focused on operational logistics and microplanning at the union council level, drawing on experience from measles, typhoid and polio campaigns.

Officials said 20 million girls aged nine to 14 are registered in schools nationwide, with the remainder out of school. An estimated 70% of vaccinations will take place in schools and the rest are to be administered in community settings through partnerships with public and private sectors.

What is HPV?

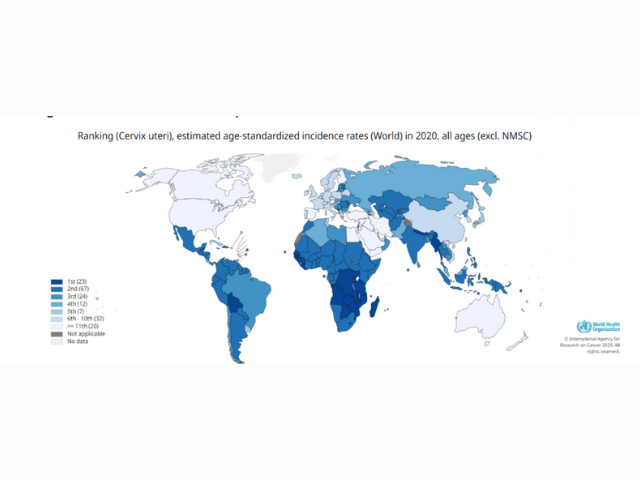

Cervical cancer kills more than 300,000 women worldwide each year, with the heaviest death toll in low- and middle-income countries. In Pakistan, the disease is among the leading cancers in women and is often diagnosed too late, despite being largely preventable through timely vaccination.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) — a sexually transmitted infection — is responsible for 91% of cervical cancers globally. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 291 million women are diagnosed annually and about 340,000 die from the disease, most in countries like Pakistan.

Recent estimates indicate that every year in Pakistan, 5,008 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 3,197 die from the disease, according to the Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet 2023.

HPV has over 200 known types, classified into low-risk and high-risk categories. While most low-risk infections are asymptomatic and resolve on their own, high-risk strains HPV 16 and 18 are linked to 70–80% of cervical cancer cases. In Pakistan, nine out of 10 cases are caused by these two strains. The country reports about 5,000 new cases and 3,000 deaths each year, with 73–74 million women at risk.

The HPV vaccine is most effective for girls aged nine to 14, but coverage is hindered by data gaps, slow rollout and social barriers. Pakistan’s age-standardised incidence rate is 6.1 per 100,000 women — above the WHO’s recommended threshold of four or fewer. The WHO’s 2020 global strategy calls for vaccinating 90% of girls in this age group by 2030, but global uptake remains below 15% due to delays in national programmes.

The Zekolin vaccine being introduced in Pakistan protects against HPV types 16 and 18, which modelling by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) suggests could prevent up to 83% of cervical cancer cases in the Eastern Mediterranean, Central, Western, and Southern Asia. Newer-generation vaccines covering multiple HPV types could increase protection to 95%.

Top down approach vs community-led engagement

The HPV campaign’s success in Sindh will depend not only on logistics but also on addressing deep-rooted social inequities. A technical, top-down approach risks alienating communities already excluded from decision-making, underscoring the need for participatory strategies that treat local populations as equal partners in health initiatives.

Pakistan’s entrenched health and education inequalities cannot be resolved by technical fixes alone, warned Dr Kausar S Khan, a public health researcher and human rights activist, calling for participatory action research and community-led engagement as the foundation of social policy.

The country’s policy and academic elite — researchers, senior bureaucrats and service providers — form a small, privileged minority, while “the poor, women, minorities, transgender people, and those with different sexual orientations” make up the majority yet remain excluded from decision-making, stressed Dr Khan.

“In Karachi, more than 50% of the population lives in kachhi abadis without water, electricity, or sanitation — and yet we want to take science to them,” she said, warning that a science-heavy, top-down approach ignores participatory ethics and local realities.

Drawing from her work in participatory action research, Dr Khan urged a “power-based, strength-based approach” that begins with “knowing yourself” and treating communities as equal partners rather than passive recipients of awareness campaigns by focusing on women development department for HPV vaccination initiatives. This, she underscored, is lacking in the campaign.

However, the assumption that vaccines and other technical interventions can address deep-rooted social problems is incorrect.

“The successes we see are technical. But the social side is where it was,” she said, stressing that performance indicators and programmatic processes cannot replace genuine community inclusion.

Gaps and awareness

Awareness of cervical cancer and the human papillomavirus (HPV) in Pakistan remains alarmingly low, with entrenched cultural norms and gender dynamics posing major challenges to HPV vaccine uptake, according to Jhpiego’s KAB [Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior] Study and UNICEF’s Qualitative Research and Co-creation Insights.

The study found that only 17.2% of respondents were aware of cervical cancer, a mere 4.4% of caregivers had heard of HPV, and only 2.9% knew of the HPV vaccine’s existence. UNICEF officials said the fear of cancer could be a motivator, but misconceptions about hygiene, fatalistic beliefs, and women’s limited role in healthcare decision-making severely hinder acceptance.

Language and framing were found to influence perceptions — “vaccine” evoked hope and prevention for adolescent girls, while “injection” triggered a fear of needles and illness. UNICEF’s co-creation sessions emphasised portraying girls as aspirational subjects rather than vulnerable objects, and using images that reflect real communities instead of idealised versions.

Awareness about the HPV vaccine is particularly low, with 95% of people surveyed having never heard of it. However, trust in official guidance is high — 90% said they would accept the vaccine if recommended by the government, a doctor, or religious leaders. Around 76–81% expressed interest in cervical cancer or HPV screening, and 79–80% said they would vaccinate themselves or their daughters.

Barriers include access to vaccines, family objections, minor fears about pain or side effects, cost concerns, and embarrassment due to misconceptions about the vaccine’s necessity. Reluctance is notably higher among mothers than daughters.

Mothers emerged as the key gatekeepers for consent, due to their close communication with daughters, while fathers — often uninvolved in daily health decisions — hold passive approval that can stall campaigns.

“In fact, mothers who exhibited a greater knowledge of cervical cancer showed a more [bigger] risk of not wanting to vaccinate their daughters compared to those who had never heard of it,” noted Dr Fyezah Jehan, Professor and Chair at AKU. “It is trust and reassurance, and addressing these concerns, that will allow us to manage it better.”

She added that acceptance is highest when mothers understand both the benefits and the safety of the vaccine, without having general concerns about childhood immunisation.

Social listening efforts by UNICEF and other partners are underway to identify local concerns and adapt communication strategies to build vaccine confidence and prevent hesitancy. Findings indicate that both parents and health workers require targeted engagement.

“We need to convince our vaccinators, our health workers even more that this vaccine is good, and then they will transmit that confidence…to the communities and the key stakeholders,” said Dr Paul Bloem, WHO HPV Vaccine Senior Technical Officer, stressing the need for continuous training to reinforce trust.

Despite strong safety data, rumours persist, particularly claims linking the vaccine to infertility. The global vaccine safety committee has repeatedly reviewed such allegations and found “no association between HPV vaccination and infertility”. Experts note the vaccine may actually help prevent infections that can reduce fertility.

Evidence from other countries, such as Bangladesh, shows that careful preparation and adopting a one-dose strategy can achieve national coverage rates above 90% at launch. Officials warn that without similar groundwork in Pakistan, achieving high coverage from the outset — critical for long-term success — will remain out of reach.