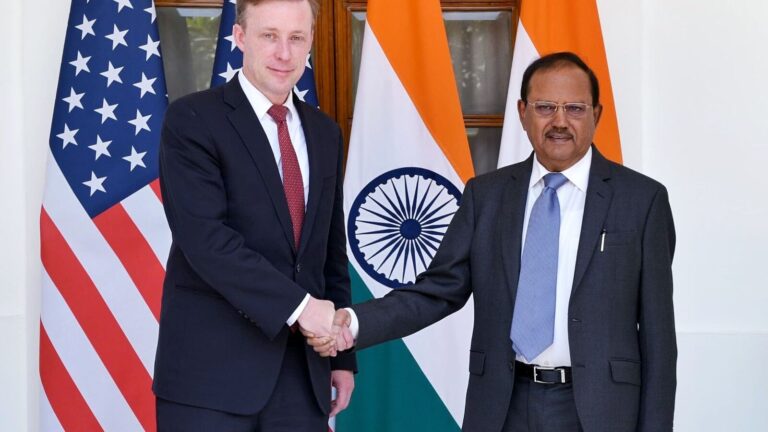

Can India help the United States win the race against China for technological dominance? The Biden administration appears to think so. Following a visit to New Delhi by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the White House on Monday released an ambitious fact sheet listing current areas and proposals for U.S.-India cooperation on “critical and emerging” technologies, including semiconductors, fighter engines, spaceflight, communications, biotechnology and artificial intelligence.

Can India help the United States win the race against China for technological dominance? The Biden administration appears to think so. Following a visit to New Delhi by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the White House on Monday released an ambitious fact sheet listing current areas and proposals for U.S.-India cooperation on “critical and emerging” technologies, including semiconductors, fighter engines, spaceflight, communications, biotechnology and artificial intelligence.

The statement did not mention China. But shared concerns about Beijing’s ambitions underlie an initiative on critical and emerging technologies launched last January. “To put it bluntly and boldly, this is first and foremost about de-risking and diversifying from China,” Rudra Chaudhuri, director of Carnegie India, said in a phone interview.

Hello! You’re reading a premium article! Subscribe now to continue reading.

Subscribe now

Premium Benefits

Premium for those aged 35 and over Daily Articles

Specially curated Newsletter every day

Access to 15+ Print Edition Daily Articles

Register-only webinar By expert journalists

E-Paper, Archives, Selection Wall Street Journal and Economist articles

Access to exclusive subscriber benefits: Infographic I Podcast

35+ Well-Researched Unlocks

Daily Premium Articles

Access to global insights

Over 100 exclusive articles

International Publications

Exclusive newsletter for 5+ subscribers

Specially curated by experts

Free access to e-paper and

WhatsApp updates

The statement did not mention China. But shared concerns about Beijing’s ambitions underlie an initiative on critical and emerging technologies launched last January. “To put it bluntly and boldly, this is first and foremost about de-risking and diversifying from China,” Rudra Chaudhuri, director of Carnegie India, said in a phone interview.

These concerns are well-founded: Over the past four decades, China has transformed itself into a science and technology superpower, surpassing the United States in 53 of 64 key emerging technologies, including advanced aircraft engines, electric batteries, machine learning and synthetic biology, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

In the Leiden World University Science Rankings, Chinese universities occupy 10 of the top 20 positions, while US universities have only five in the top 20. China graduated 1.4 million engineers in 2020, seven times the number of US university graduates that year.

Chinese tech companies such as CATL (electric batteries), BYD (electric cars) and Huawei (telecommunications) have global influence and global ambitions. “The old scientific world order dominated by the US, Europe and Japan is coming to an end,” The Economist magazine recently declared.

Much of the U.S. response to the China challenge will depend on cooperation with technologically advanced allies in Western Europe and East Asia. For example, the U.S. is working with the Netherlands, home to ASML, a maker of semiconductor chip-making equipment, to help the West maintain its technological edge.

At first glance, India seems an unlikely technology partner. It has only one university in the top 200 in the Leiden University Rankings. India spends only a fraction of what China and the US spend on R&D. In 2020-21, the Indian government and private sector combined spent less on R&D than Huawei and Microsoft alone spent on R&D in 2021. Of the top 100 technology companies by market capitalization, there is not a single Indian company, 58 are US and 9 are Chinese. The Netherlands, with a population 80 times smaller than India’s, has five companies in the top 100.

But Washington sees value in increased bilateral cooperation. In a phone interview, Samir Lalwani, a research fellow at the United States Institute of Peace, outlined three big reasons for this: First, if the U.S. were to hold its technology standards to the same level as India’s, it would make it more difficult for Chinese companies to enter the Indian market, and the so-called Global South as well.

Second, the U.S. is looking to tap into India’s tech talent. For decades, many of India’s best scientists have headed straight for the U.S. But there are several factors that make India’s domestic ecosystem worth engaging with, including its vast pool of engineers, homegrown successes in space exploration and digital infrastructure for electronic payments, and a burgeoning tech startup scene.

Third, the United States believes that technological cooperation will boost India’s military capabilities and deepen the trust needed for military cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. GE Aerospace and India’s Hindustan Aeronautics are in talks to jointly produce fighter jet engines that could help India thwart Chinese border incursions. India’s U.S.-made MQ-9 drones could easily coordinate with tracking Chinese naval vessels in the Indian Ocean. Carnegie’s Chaudhri said using India as a manufacturing base for military equipment could allow the United States to export weapons to parts of Asia and Africa more cheaply.

The optimism is not entirely unfounded. In recent years, India has signaled its desire to be part of a tech sphere aligned with the United States. It has barred China’s Huawei and ZTE from its 5G networks and joined a U.S.-led “remove and replace” program to remove suspect Chinese equipment from U.S. telecommunications infrastructure. Apple subcontractors Foxconn and Pegatron have invested in India, and the Modi government is encouraging Tesla to follow suit.

The Indian military has historically maintained close ties with Russia, but that relationship has declined in importance sharply. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that just 36 percent of India’s arms imports from 2019 to 2023 will come from Russia, down from 76 percent a decade ago. Russia’s growing reliance on China is likely to accelerate India’s search for more reliable partners in the West.

Still, there’s no guarantee that U.S.-India tech cooperation will succeed. India expects the U.S. to treat it like an ally by exempting it from export controls for sensitive technologies, but critics in Washington say New Delhi doesn’t always behave like one. They point to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, India’s alleged assassination plot against a Sikh separatist in New York, and Modi’s government’s refusal to condemn its crackdown on domestic critics. Washington’s bet on New Delhi is based on a belief that “India is a forward-thinking international actor,” says Lalwani of the U.S. Institute of Peace. For the new tech cooperation to realize its potential, India needs to reassure skeptics that its future lies in the democratic world.

Stay tuned for all business news, market news, breaking news events and breaking news on Live Mint. Download the Mint News App to get daily market news.