List Feng for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

List Feng for NPR

Last summer, New Mexico state special agents inspecting a farm found thousands more cannabis plants than state laws allow. Then on subsequent visits, they made another unexpected discovery: dozens of underfed, shell-shocked Chinese workers.

The workers said they had been trafficked to the farm in Torrance County, N.M., were prevented from leaving and never got paid.

“They looked weathered,” says Lynn Sanchez, director of a New Mexico social services nonprofit who was called in after the raid. “They were very scared, very freaked out.”

They are part of a new pipeline of migrants leaving China and making unauthorized border crossings into the United States via Mexico, and many are taking jobs at hundreds of cannabis farms springing up across the U.S.

An NPR investigation into a cluster of farms, which the industry calls cannabis “grow” operations, in New Mexico found businesses that employ and are managed and funded largely by Chinese people. They’re seeking opportunities in a flourishing U.S. cannabis market after the coronavirus pandemic led to a global economic crisis. But some of the businesses have run afoul of the law, even as states such as New Mexico have legalized marijuana.

Getting out of China

One of the workers encountered at the farm in Torrance County is 41-year-old L., who came from China’s central Hubei province a year ago. He asked NPR to use only his first initial because he is anxious about legal prosecution in the U.S. and China.

L. told NPR he struggled to find work in China during the pandemic lockdown. He was forced to move out of his home after a state developer demolished his house to make way for a new project, but his new apartment was never built and he lost his deposit. When L. went to the developer’s office to protest, he got into a physical fight with employees of the company and was jailed.

That was when a disillusioned L. saw videos on Douyin, a sister app of TikTok in China, about people purportedly earning good money in the United States.

“There was one influencer who kept messaging me his pay stubs in California showing how he was making 4-, sometimes $5,000 a month and telling me how easy it was,” L. says. He got in contact with an agent who promised to help him get to the U.S.

Watching Douyin videos, L. learned how to zouxian, or “walk the line,” to the U.S.-Mexico border. First, he flew to Turkey, then Ecuador. He then took a grueling, monthlong trip from South America to Mexico that included buses, boats and a long walk through the hazardous Darién Gap jungle.

“The journey was full of countless trials and tribulations,” says L. He was robbed twice in Latin America and feared he might die from exposure but crossed into the U.S. in May 2023.

On a path also regularly used by Caribbean and South American migrants, now large numbers of Chinese migrants are taking this land route. U.S. border authorities say they encountered 37,000 Chinese people who crossed irregularly into the U.S. southern border last year — more than the past 10 years combined.

Border officials apprehended L. but released him in July, pending review of his asylum claim. He rented a room in Southern California’s Monterey Park, which is home to a large Chinese immigrant community. There, fellow Chinese immigrants introduced him to labor agencies that promised to place workers without documentation for a $100 fee.

One agency’s Chinese-language social media ad for “cutting grass” in a greenhouse caught L.’s eye. It offered to pay $4,000 a month in cash for what seemed like easy work, he says. Borrowing a cellphone, he dialed the number listed.

A supply chain for labor

From California, L. and a handful of other recent Chinese migrants were driven to a New Mexico grow operation called Bliss Farm.

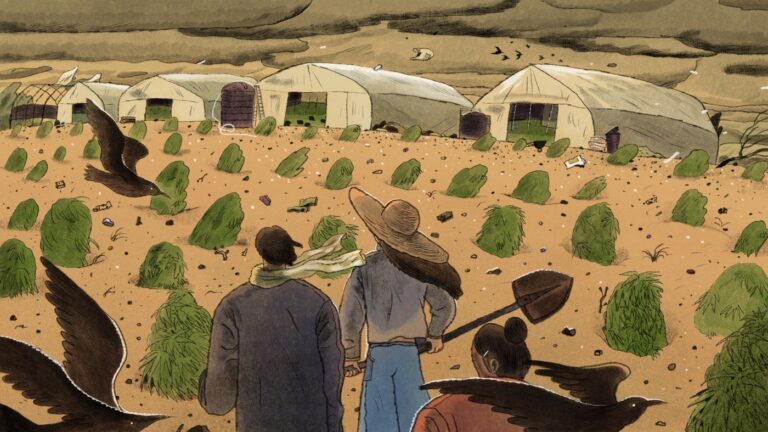

They were shocked by what they saw — a hodgepodge of about 200 greenhouses — but because their phones and passports had been taken by their managers, they felt obligated to stay, workers say.

“The farm said it would cover food and shelter, so you could save all your wages,” a Bliss Farm worker, from China’s northern province of Shenyang, told NPR. “But the farm was just a big dirt field.” He also requested anonymity because he is applying for asylum in the U.S. and fears being sent back to China.

He says he regularly worked 15-hour shifts, alongside the greenhouse’s manager, a man from China’s Shandong province, and the manager’s relatives.

At the end of their shift, the managers left, and the workers slept in wooden sheds with dirt floors, three workers NPR interviewed say. None of them were paid before the operation was shuttered.

New Mexico authorities say a tip about worker conditions and zoning violations led them to visit the farm last year.

“Just a very disastrous grow. There was trash, water, fertilizers, nutrients, pesticides leaking into the ground,” says Todd Stevens, director of the state’s Cannabis Control Division. “As soon as the officer stepped in, I think red flags started going off everywhere.”

Authorities raided Bliss Farm in August 2023.

Sanchez, director of the New Mexico social services nonprofit The Life Link, describes the condition of laborers she encountered there.

“They had burns, visible burns on their hands and arms. … The chemicals, they told me it was from the chemicals,” Sanchez says. “They looked very malnourished.”

L. and two other workers NPR interviewed were among those found at the farm. They’ve applied for asylum in the U.S. and their cases are pending.

State authorities revoked Bliss Farm’s license and fined it $1 million for exceeding state grow limits.

Immigrants from Ecuador warm themselves after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border on March 6, in Campo, Calif. Migrants from Ecuador, China, Georgia and other nations waited for U.S. Border Patrol agents to collect them to process asylum claims.

John Moore/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

John Moore/Getty Images

Immigrants from Ecuador warm themselves after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border on March 6, in Campo, Calif. Migrants from Ecuador, China, Georgia and other nations waited for U.S. Border Patrol agents to collect them to process asylum claims.

John Moore/Getty Images

“Trying to get in on the money train”

Weed has become big business in the U.S., where about half of states have legalized it for adult recreational use and about two-thirds have legalized medical use. Despite federal law still prohibiting marijuana, states swapped out local penalties for new rules to regulate sales, create tax revenue and stimulate economic growth.

New Mexico is one of them. In 2021, it legalized the recreational use of marijuana, after it was already long legal for medical use, and permitted growers to raise a limited number of the plants. That set off a scramble to purchase residential land for cannabis grows.

“So many people were interested in trying to get in on the money train, so to speak, right from the start,” says Don Goen, a planning and zoning director in New Mexico’s Torrance County who has investigated waste and water usage complaints related to marijuana growing. “Some really knew what they were doing and others, it was more of a dream than it was a reality.”

Investigations by nonprofit news outlet ProPublica have found links between Chinese diplomats, Chinese Communist Party-affiliated organizations, local Chinese criminal syndicates and some marijuana operations in the United States.

In the operations reported on in this story, NPR found no signs of Chinese state or Asian organized crime involvement. The businesses did attract small-scale, individual investors from China who were eager to invest abroad.

Ella Hao, an accountant from China’s northern Shandong province, says she moved with her husband to Los Angeles in 2020 during the start of the pandemic, in part to secure new passports for their two U.S.-born children.

In September 2020, following the recommendation of two other Chinese-speaking immigrants, Hao and her husband decided to invest about $30,000 in a New Mexico marijuana farm near the town of Shiprock, according to handwritten receipts seen by NPR. “We invested on the strength of the recommendation from someone we thought was a close friend,” Hao says.

Shiprock is on the Navajo reservation in New Mexico. And the farm had been started by Dineh Benally, a former Navajo Nation farm board president, who is currently dealing with numerous legal challenges over cultivating hemp on Native land.

In 2022, Hao and her husband paid another $300,000 to buy a plot of land in neighboring Oklahoma in a joint purchase with another recent emigrant from China. She convinced them that setting up greenhouses to grow marijuana there would be even more lucrative than in New Mexico.

Despite successfully applying for a grow license under her friend’s name, the Oklahoma grow never started operations, papers show.

“Our land prices are really cheap. There really was no enforcement going on until we started looking at this,” says Donnie Anderson, director of the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics. “So I think it was just really a perfect storm.”

Trouble at other grow operations

Just a few miles from Bliss Farm, authorities zeroed in on another, unrelated marijuana grow in Shiprock, N.M. — started by Navajo Nation entrepreneur Benally.

In September 2023, 15 Chinese workers brought a lawsuit alleging that Benally and his associates made the laborers work 14-hour shifts with no pay at the Shiprock operation, that managers physically abused the laborers to get them to work harder and that guards prevented the workers from leaving.

After Benally obtained a license to start a new operation in Torrance County, County Commissioner Samuel Schropp visited the Shiprock site.

“I saw a shed with bunks built floor-to-ceiling like a submarine, stacked 18 inches apart, and a number of RVs with no hookups, [no] water or sewer hooked up to them, and electric cords laying in the mud in the water,” Schropp says.

Some of the workers came from Chinese-speaking immigrant communities in New York. They were people who had worked in restaurants, nail salons, massage parlors and other industries hit hard during COVID, says Aaron Halegua, a lawyer representing the 15 workers.

New Mexico authorities revoked the farm’s license and fined it $1 million for exceeding state growing limits and other violations.

NPR’s efforts to reach Benally were unsuccessful. This past April, Benally tried to dismiss the workers’ lawsuit against him, arguing that federal law had no jurisdiction over his case. Reporting by the nonprofit investigative outlet Searchlight New Mexico published in April suggested he was still growing marijuana.

Benally had partnered with a number of Chinese businesspeople to get the Shiprock operation started, according to a work agreement seen by NPR.

In early 2022, one of the partners, real estate agent Irving Rea Lin, was arrested in California during a months-long crackdown on illegal grows. And one of the operation’s backers, a solar panel entrepreneur named Xiaofeng Peng or Denton Peng, is a fugitive who is wanted in China on fraud charges. He did not respond to NPR’s request for comment.

Another associate named Bryan Peng (not related to Xiaofeng Peng) started a grow in Oklahoma, which used some of the same Chinese workers from their Shiprock farm. In 2022, that grow was raided as well and shut down.

That November, an investor named Chen Wu killed four workers on the farm demanding a $300,000 investment back. Wu is serving a life sentence in prison.

The investor Hao says she lost a lot of money in the businesses she invested in. Her $30,000 was not returned when the Shiprock farm closed, she says. And the Oklahoma operation where she sank $300,000 — her family’s life savings — disappeared after Hao discovered her name had been omitted from all the land deeds and the business license.

“Because we do not speak English, we could not read any of the documents and licenses or dispute the facts in any legal case. We do not know where to turn,” Hao says.

Too ashamed to return to China, Hao says she has been raising her two young children in California by finding short-term jobs.

Her most reliable gig has been pruning marijuana plants at a licensed California grow operation.

NPR’s Emily Feng reported from Taipei, Taiwan. KUNM’s Alice Fordham contributed reporting from Torrance County, N.M. NPR’s Greta Pittenger contributed research from Seattle.