“There was a lot of disruption,” he said. “Tariffs were imposed without much planning. Markets were lost. Costs rose. Relationships strained.”

By Yang Shilong, Li Xirui, Liu Yanan

MANNING, United States, June 8 (Xinhua) — The Renze family’s fleet stretches from six-monitor John Deere tractors to a pristine 1929 Ford Model A, a symbol of a time when farming was hands-on, not high-tech.

At 97, Melvin Renze, the family patriarch, still drives his Ford down Main Street to Deb’s Corner Café. On other days, he wanders into the fields, running his fingers through the soil and offering advice to his sons: “You ought to do this, or that!”

“I’m busy all the time,” he said. “I was born a farmer. It’s in my blood. If I had a do-over, I’d do exactly the same. I like farming. I did like farming.”

The Renzes have farmed in western Iowa for generations, managing thousands of acres of farmland and a significant number of livestock. Melvin’s son, Scott, stays in the field, dealing with unpredictable markets, precision technology and the ripple effects of U.S.-China trade friction. His brother, Randy, took a different path, branching into international agribusiness.

Despite the support of advanced technologies, such as GPS-guided tractors, cloud-connected feeding systems and data-informed crop decisions, their concerns revolve around cost, policy consistency and international cooperation.

FLICKER OF RELIEF

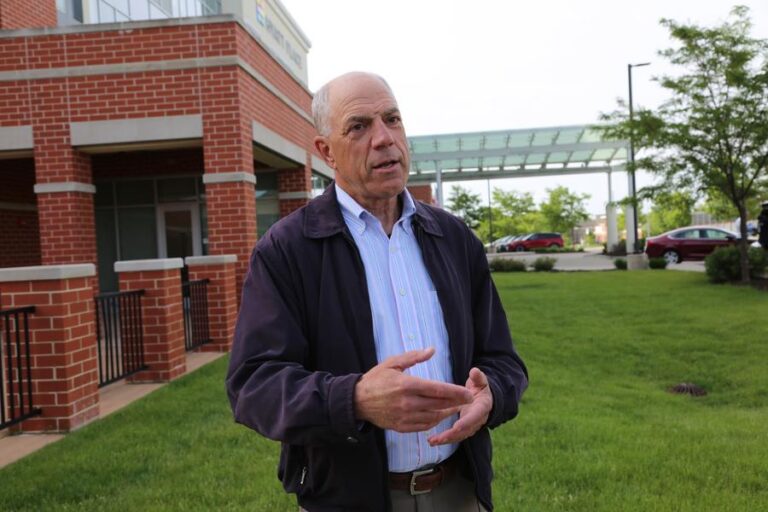

A temporary 90-day suspension of tariffs between the United States and China in May brought a flicker of relief. But Randy, who spent 34 years navigating global trade standards at leading tractor maker John Deere, sees a more complicated picture.

“When tariffs were imposed the first time, it cost John Deere. It cost the American farmer,” he told Xinhua in a recent interview. “Those soybean markets we lost, someone else filled.”

Scott felt the impact firsthand. “By spring, we’ve already spent hundreds of thousands on seed, fertilizer and chemicals,” he said. “No policy from Washington is going to stop us short-term. But next year? We’ll have to rethink everything.”

Noting that a single breakdown can cost tens of thousands of dollars, Scott said: “With tight margins, even a 10-percent drop in prices can shake everything (up) — land payments, equipment loans and family income.”

Today, most of their corn heads to nearby ethanol plants; some goes to livestock feed; the rest is exported. However, tariffs are rebalancing that mix, Scott said. China was once the largest buyer, but now “I can’t tell you the amount. We’re constantly renegotiating,” he added.

Technology shapes every aspect of their operation. The Renzes manage a digital command center and use apps to track weather, monitor soil, mix cattle feed and hedge commodity prices. “We’re not just farmers anymore. We’re managers, marketers, engineers,” said Scott.

Still, it’s not necessarily easier. “Physically, sure. It’s less labor. But mentally, it’s exhausting. You’re troubleshooting tech, watching markets, managing risks every day,” he added.

“WE HEDGE, WE WATCH, AND WE ADJUST”

Every growing season is a gamble. “Some years, you make 100 U.S. dollars an acre. Another year, you lose 50 dollars,” Scott said. “One hailstorm, one drought, and everything changes,” he added, noting that insurance only offers limited safety, as coverage is costly and incomplete.

That’s farming in 2025: sophisticated, strategic and still uncertain.

Despite that, Scott stays committed. “We’ve got apps, data, tech. We do everything right. But we can’t control tariffs, politics or the weather. So we hedge, we watch, and we adjust.”

Asked whether tariffs come up often in conversation, Scott shrugged. “Tariffs? That’s beyond our control. We leave it to the government and hope they manage it well,” he said. “We just try to survive it.”

Even with the help of high-tech machinery, managing thousands of cattle and vast stretches of land comes with real pressure.

“Farming today isn’t blue-collar or white-collar,” Randy said. “It’s both. You need the brains and the back.”

The same tech that boosts efficiency also drives up costs. “That planter? 300,000 dollars,” said Scott. “We’ll spend another 15,000 dollars a year just to maintain it.”

Competition from Brazil, Argentina and elsewhere is also mounting. “You’ve got to be the best. Efficient, informed and relentless,” he said.

Tariffs are now another variable.

“Tariffs won’t affect the next two to five months,” Randy said. “But come next season, it’ll impact what we plant and what we sell and buy.”

BUILDING TRADE TIES WITH HANDSHAKES

Randy has visited China many times, working with farmers, officials and engineers. That experience taught him patience and pragmatism.

“China takes the long view,” he said. “Thousands of years of history puts a few years of friction into perspective.”

Randy sees people-to-people diplomacy as vital, especially when politics turn tense.

“You don’t build trade relationships with speeches. You build them over years through handshakes, visits, and showing up,” he said. “That work doesn’t stop just because leaders change.”

He was frank about the U.S. administration’s trade policies: “There was a lot of disruption,” he said. “Tariffs were imposed without much planning. Markets were lost. Costs rose. Relationships strained.”

Instead of fine-tuning agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement or joining alliances like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, “we scrapped and restarted,” he said. “It may look strong on paper, but it makes long-term planning impossible for companies and farmers alike.”

DEEPER MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING NEEDED

Randy still has the old slides from John Deere’s presentation in China, photos with Chinese friends and every business card he received. On his wall hangs a map of China, marked with stickers from every city he has visited.

“It wasn’t just business,” he said. “It was relationships, understanding and trust.”

He hopes Chinese friends can understand American farmers, as well as their resilience, hopes and joy over a good harvest.

What’s needed, he said, is deeper mutual understanding.

Now retired, Randy volunteers at the World Food Prize Hall of Laureates in Des Moines, capital of Iowa.

“I grew up in industrial agriculture. The Prize is about developing countries,” he said. “It’s been fascinating — a way to give back.”

Through that work, he has expanded his knowledge of global food issues, China-Iowa ties and agricultural diplomacy.

“We can be part of the solution,” he said. “I hope we continue to be.”■