Forty-four years later, Long and others involved in the Supreme Court case said seeing Louisiana enact a nearly identical law was like watching history repeat itself, threatening the boundaries of church-state separation they have fought to maintain.

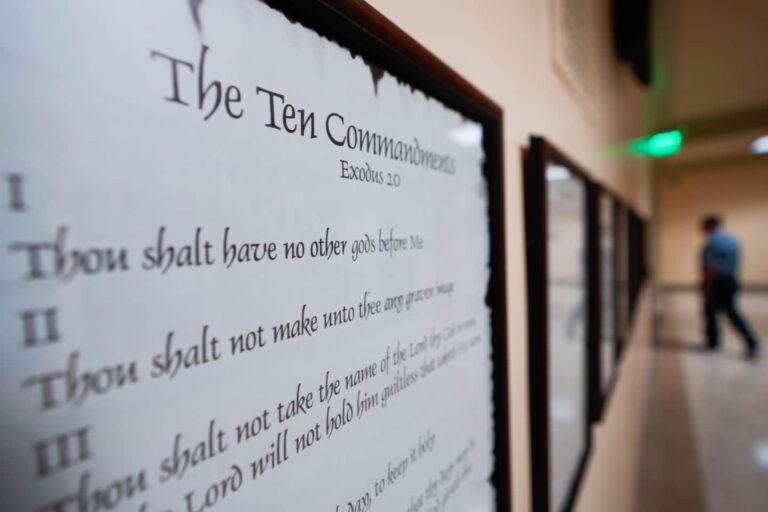

Louisiana was the first state to require the Ten Commandments in public schools since a 1980 Supreme Court ruling, and nine plaintiffs filed a lawsuit this week alleging the law violates parents’ rights. Louisiana’s governor has welcomed the lawsuit, and experts say it will test the new legal environment created by a conservative-leaning Supreme Court.

Long said he’s not surprised that these tensions are flaring up given the country’s political climate, but added that the answer lies in the Constitution. “Just as we want the government to be free from religion, we want religion to be free from the government,” Long said.

Others have noted that the issue has resurfaced. “My first reaction was, Really? Are you kidding me? Open up a history book,” Vivian Stone Taylor, whose grandmother was one of the four plaintiffs in the 1980 case, told The Washington Post. “This issue has already gone all the way to the Supreme Court.”

Like the lawsuit filed this week. Louisiana, The Kentucky lawsuit included people from a range of religious and political backgrounds, including Unitarian housewife and activist Sydelle Stone, atheist Republican district chairwoman Bowers, Catholic public school teacher Patricia Bricking and Rabbi Martin Perley.

The four plaintiffs argued that the law was unconstitutional and ignored the separation of church and state, while supporters of the law argued that the nation was founded on the ideals of the Ten Commandments, according to interviews with local media at the time (supporters of Louisiana’s law made similar statements).

Marvin Coan, who helped lead the lawsuit with William Stone, took it on in his first year as general counsel for the ACLU of Kentucky. Coan said neither he nor Stone anticipated how far the case would escalate. Stone could not be reached for comment.

Kentucky law required then-Superintendent of Public Schools James Graham to post the Ten Commandments in every public classroom. To avoid legal disputes, he stipulated that the money for the posts must come from donations, not taxes, and that the posts must include a statement that positions the Ten Commandments as “the fundamental code of Western civilization and the common law of the United States.” (Louisiana law has a similar requirement.)

Coan and his team lost in Franklin County Circuit Court. They appealed, and the Kentucky Supreme Court also ruled in the state’s favor. They took the case to the Supreme Court.

As the case played out in court, Stone-Taylor said, her grandmother, Sydell Stone, was routinely accused of not believing in God. (Stone-Taylor, 52, said her grandmother certainly did.) Patricia Bricking faced the wrath of devout Catholic relatives, her daughter Elizabeth Bricking, 55, told The Washington Post, who resented her for taking part in public protests. Long said he remembers his mother nearly being run off the road while returning home to Louisville after testifying against the law at the state Capitol.

The Supreme Court overturned the Kentucky decision without oral argument in November 1980, an unusual move that showed how clear the law is on the issue, Coan said.

“These opinions and summary judgments are overturned because a sufficient number of justices believe the outcome is clear in law and no further debate is necessary,” he said, adding, “The United States Supreme Court has had a number of very well-established First Amendment cases, and as a result, five of the justices have said, ‘We don’t need to be briefed on this, we don’t need to debate it.'”

Stone-Taylor said she remembers her grandmother calling her on the day the Supreme Court’s decision came out, after two years of family discussions about the law. But the decision wasn’t a surprise to her, she said. “She knew they were right,” Stone-Taylor recalled.

Elizabeth Bricking, then 12, pretended to be sick so she could miss school. A “Good Morning America” segment was coming out about the family and their involvement in the lawsuit, and she couldn’t wait to watch it. “I was happy to be on the news,” she laughed. “I pretended to be sick because I didn’t think the teachers would stop and watch.”

After the Supreme Court decision was announced, Bricking’s family’s phones kept ringing off the hook. “I was just taking those messages,” she said, as reporters called to talk to her mother.

“We’ve had some angry phone calls,” she said, “angry people yelling abuse at us.”

Her mother rushed home. “She was like, ‘We won, we won!’ She was so excited,” Patricia Bricking said.

William Stone, the lead attorney on the case, told The Courier Journal at the time that the ruling was a landmark in a decade.

“I think this signals that the Supreme Court is still here to protect the Constitution,” he said, according to the paper. “I think this will be one of the most important Supreme Court decisions of the 1980s.”

Kentucky’s law did not pass. Lemon vs. Kurtzman The Lemon test is a test to determine whether a law violates the First Amendment’s separation of church and state clause. To pass the Lemon test, a law must meet three criteria: it must have a secular purpose, it must have a predominantly secular effect, and it must not create “undue entanglement” between government and religion.

“Kentucky’s law doesn’t even pass the first test,” Coan said. “What secular purpose does it have? None. It’s deeply religious in nature.”

He added that the “excessive intertwining” of government and religion was also evident: “If the government is mandating the posting, how could there be any greater intertwining?”

Coan said he expects Louisiana’s law will suffer the same fate.

But some legal experts say the country is now treading in uncharted territory. Recent Supreme Court decisions have been more tolerant of religion in schools. For example, in 2022, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a Washington State University football coach who knelt in the middle of the field to pray and was joined by student athletes.

“The Supreme Court has moved away from decisions of the ’70s and ’80s,” said Steven Smith, a law professor at the University of San Diego. In the Washington State University football coach case, the Supreme Court decided something that “wouldn’t have happened 20 or 30 years ago,” he said, by throwing out the very Lemon test that defined the 1980 case.

The court said it would instead follow “history and tradition,” Smith said. What that means remains unclear.

“At this point, it’s really unclear which direction the court is going to go,” Smith said. “I don’t think people who are confident in either decision are very justified at this point.”

Still, Coan is confident the Kentucky precedent will stand.

“I may be in the minority, but I don’t think the court will go that far,” Coan said. “I’m confident common sense will prevail.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report.