Why would a common Chinese noodle maker be buried in a tomb fit for an emperor?

And why was a blonde Westerner important enough to be memorialized on that wall?

Archaeologists in northern China have unearthed a small but richly decorated 1,200-year-old tomb in the mountains outside Taiyuan, the capital of northern China’s Shanxi province.

It dates from China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907), a period that coincides with the end of the Dark Ages in Western Europe.

And it’s full of surprises.

The Shanxi Provincial Archaeological Institute first made the discovery during a road construction survey in 2018, but the institute only recently announced its findings, according to the state-run Xinhua News Agency.

The tombstone inscription states that the master died at home in the 24th year of the Kaiyuan era (736 AD) at the age of 63.

His wife, Guo, was also buried there in the same year.

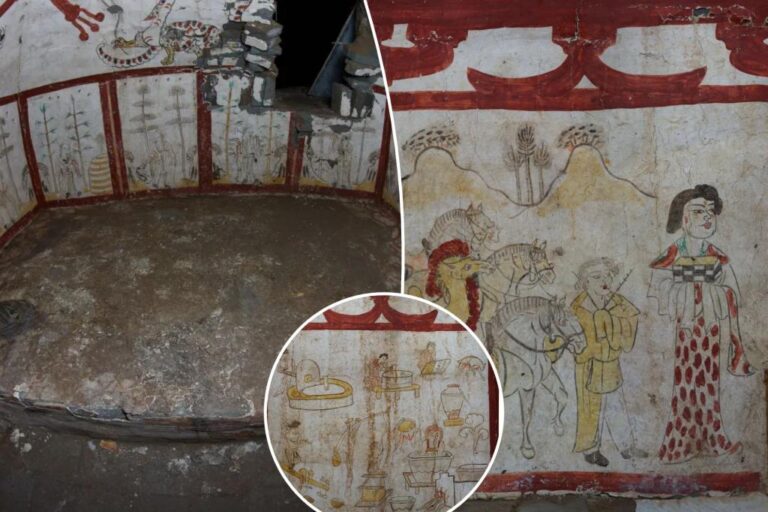

Archaeologists discovered a very well-preserved, brightly colored, single-room brick structure.

The whitewashed walls and ceiling are adorned with red, yellow and orange hues, and within it stands a stone coffin bed in which the couple is believed to have been laid to rest.

But the clear, vivid artwork caught the eye of researchers.

It does not tell the tales of great battles or successful hunts that one might expect.

Nor does it aim to place the people who live there in the splendor and splendor of a royal court.

Instead, the mural depicts them hard at work under the watchful eye of magical beasts.

And trade with Westerners.

Noodle maker

Bold and spectacular botanical designs decorate the entrance, and three pairs of yellow-robed figures line the entrance and walkway.

The two men at the door were carrying jade stone slabs, and Xinhua reported they identified themselves as “gatekeepers.”

A pair of statues inside the portico appear to greet visitors.

And just inside the tomb are a pair of guardians armed with swords.

Mythical beasts (at least one of them a dragon) weave among thick red banners, dividing the conical ceiling into four equal sections, and beneath them stand twelve uniform-sized panels with red borders.

Judging by the consistency in appearance and clothing, many appear to represent men of the same Han ethnicity.

They may represent different stages in the life and career of the tomb’s unnamed owner, but experts also speculate that the stylized paintings may represent certain “virtues” of the tomb’s owner, Xinhua reported.

One shows him holding a ritual jade tablet, another shows him facing a tomb, and another shows him confronting a snake.

Other paintings show him splitting wood, pointing at a tree while holding a cup, and depicting withered, flowering plants with no people around.

One panel in particular seems to depict a couple engrossed in making rice noodles.

They carry water, thresh grain, use millstones and mortars, roll dough, and much more.

Chinese archaeologists say the strong contours, simple shading and efficient two-dimensional design set the tomb’s artwork apart from others from the same period.

“Westerners”

One of the most daring gravestone panels shows a woman wearing an ornate multi-coloured gown and carrying a plaid box.

Behind her is a blond man holding a whip, pulling three saddled horses and a two-humped camel.

Chinese archaeologists believe this indicates contact with distant lands along the Silk Road trade route, which operated for nearly 800 years before the tombs were painted.

“His facial features and style of clothing identify him as a ‘Westerner’, possibly Sogdian of Central Asian origin,” Professor Victor Xiong said. Live Science.

The Sogdians lived in the area now known as Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, which was at the heart of the Silk Road network connecting Asia and Europe.

Camels are not native to China, but they were relatively commonly depicted in Tang Dynasty artwork to highlight their importance to international trade, Xinhua said.

Whoever the noodle maker was, he had noble taste.

The South China Morning Post quoted Long Zhen, director of the Jinyang Ancient City Archaeological Research Institute, as saying that the unique artistic style is very similar to that found in the tomb of Wang Shenzi (renamed Taizu after the death of Min Taizu, founder of the Min dynasty during the Ten Kingdoms period).

The Dauphin rose through the ranks of administrator, became military governor, vizier and finally was appointed prince.

Legend has it that Wang was a frugal man and a fair judge who led his realm into an era of prosperity.

“Dr. Long hypothesized that the same artist may have painted both the king’s tomb and the newly discovered murals,” reports the South Carolina Morning Post.

However, the crown prince died on December 31, 925.

That was 189 years after the noodle maker’s grave was sealed.