Economic policy must not be driven by populist slogans or short-term political gains.

by Zheng Yin

U.S. officials have been vigorously promoting Trump’s tariff policy recently. Last month, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt tweeted on X: “American manufacturers overwhelmed with orders after Trump’s crackdown on China.”

The tweet quickly sparked debate. While some heralded it as proof that trade toughness has paid off, the reality behind such optimism is far more complex. It reflects a broader narrative of economic nationalism that, while politically potent, often overlooks basic economic logic and long-term strategic thinking.

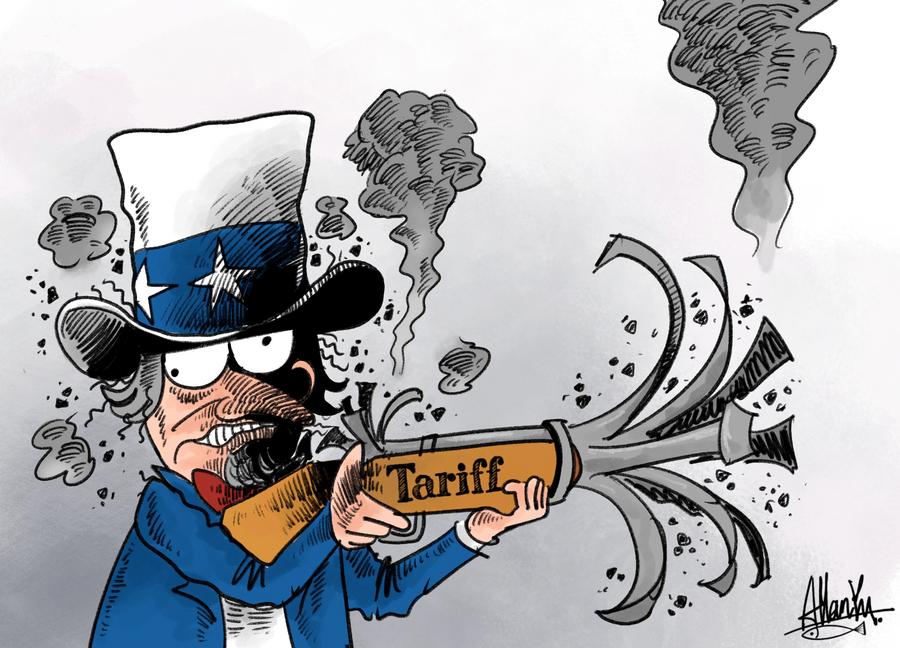

At the core of the United States’ trade approach lies “reciprocal tariffs” — the idea that the country should mirror foreign tariffs with equal or greater duties of its own. Though this might sound like fair play, international trade is not a zero-sum game. It’s an intricate system built on multilateral agreements, economic interdependence and global rules. Imposing tariffs unilaterally, without regard for these structures, disrupts markets and undermines the U.S. credibility in global trade.

Moreover, the logic behind these tariffs has significant flaws. They treat trade deficits as inherently bad and assume that tariffs can correct them. In reality, trade deficits are shaped by macroeconomic forces — currency strength, savings rates and capital flows — not merely tariff schedules. Punitive tariffs aimed at “fixing” trade deficits address only symptoms, not causes.

Ironically, the tariffs ended up harming many of the U.S. industries they were intended to protect. China responded with firm countermeasures, imposing its own tariffs on U.S. goods — especially agricultural products — hurting American farmers and manufacturers alike. Despite claims like “trade wars are easy to win,” and Leavitt’s assertion that U.S. factories are overwhelmed with orders, data tell another story.

Washington was forced to spend billions in subsidies to offset farm losses, while companies struggled with rising costs of imported parts. The net effect has been supply chain chaos, business uncertainty and a lack of any clear strategic gain.

Leavitt’s tweet underscores the U.S. government’s reluctance to acknowledge these failures. Even in the face of weak economic data, they continue to frame tariffs as strong negotiating tools. In practice, however, the policy has been reactive and incoherent — a political tactic rather than a comprehensive strategy.

Globally, these policies have triggered a reevaluation of the U.S. trade relationship. Countries are pivoting away from reliance on the U.S. market, investing instead in regional integration. The EU and Japan have signed a free trade agreement, Britain is deepening ties with India, and Asia is advancing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Trade is moving toward a more multipolar, less U.S.-centric model — an outcome likely unintended by Washington.

China, as the world’s second-largest economy and largest trading nation, has taken a principled and measured stance. It firmly opposes U.S. unilateralism and protectionism, calling such tariffs a form of economic coercion that destabilizes global markets. China has implemented targeted counter-tariffs, expanded its free trade partnerships and increased domestic support for innovation and industrial upgrading. In Q1 2025, China’s economy grew by 5.4 percent, and its trade surplus continued to expand — a testament to its adaptive strategies and long-term resilience.

Furthermore, recent U.S.-China consultations in Geneva signal a potential path back to dialogue. China has reiterated its position: negotiations must be based on mutual respect, equality and mutual benefit — principles essential for any sustainable resolution.

Economic policy must not be driven by populist slogans or short-term political gains. America’s tariff-first approach may rally a political base, but it has delivered few tangible outcomes. Sustainable trade policy must be grounded in transparency, cooperation and global norms — values that stand in stark contrast to the unilateral approaches seen in recent years.

Leavitt’s optimistic tone may capture headlines, but without facts to back it up, such claims ring hollow. The pressing question now is whether the United States can learn from this chapter and chart a more balanced and forward-looking path in global trade.

Editor’s note: The author is an international affairs observer.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Xinhua News Agency.■