Fazal Baloch’s translation, In Every Verse for You, carries Balochi poet Mubarak Qazi’s poetic fire across languages.

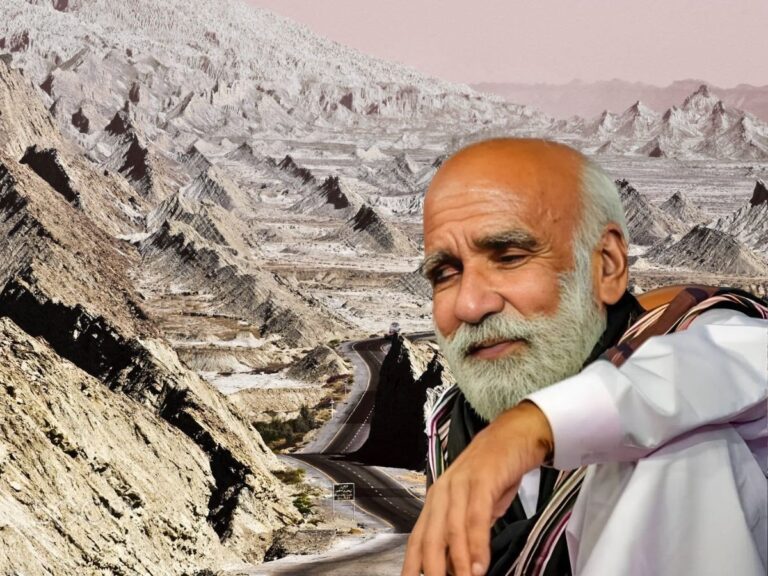

In the streets of Pasni or along its crystal-clear coast, you would often see an old man—his lips rarely parting from a cigarette, sometimes drunk, other times laughing around people. He wandered freely, never a stranger to anyone. From his hometown Pasni to distant cities and places, everyone knew him—there was no other Mubarak Qazi.

He was, in his truest form, Qazi—the poet whose final drag of a cigarette could birth verses.

Some say art should exist for its own sake, while others argue it must serve life. But beyond this debate stood Mubarak Qazi, the modern Balochi poet, who revealed art in its truest form.

His poetry was rooted in the lives of fishermen and farmers, in the rhythm of the sea and the land, in shepherds tending their herds, and in the flocks that painted the sky. He wove flowers and colors into his verses, but his true artistry lay in his deep bond with his homeland—he never separated his words from its people and very few literary figures have garnered as much praise and adoration as Qazi.

He was popular and celebrated long before his passing in 2023, firmly establishing himself in Balochi literature as a true reflection of the Baloch world’s spirit and character

Qazi’s poetry paid homage to the birds that once soared over Balochistan, to those still native to its skies, and to the ancient creatures lost to time. His verses encompassed everything—love and resistance, war and battles, oppression and injustice, the darkness that had fallen upon his land. In every form, in every line, he chronicled the soul of Baloch and Baloch’s land and with each verse, he painted poetry in its purest essence.

Born in 1955 in the coastal city of Pasni, district Gwadar, Mubarak Qazi emerged as a voice that went beyond mere verse. His poetry, filled with deep love for the Baloch and Balochistan, had a lyrical beauty that deeply touched those living under oppression.

While much of his work echoed the rhythms of war, revolution, and the resilience of people, it also embraced the mysticism of Sufism, the tenderness of love, and the serene beauty of nature. Every line he wrote carried the soul of his homeland—its colors, its struggles, its spirit—woven into verses that captured the very essence of Balochistan.

He authored ten anthologies of poetry, beginning with his debut collection, Zarnawisht (1990), and culminating in his final work, Gesa Watar Kanag Lotan (2022). Recently, a selection of his works from these ten anthologies has been translated from Balochi to English by the prominent academic, writer, and translator Fazal Baloch. Fazal titled the collection Every Verse for You, published by Balochistan Academy Turbat, 2025.

This anthology includes 110 poems, along with several ghazals and ghazal couplets. The foreword is written by the renowned poet and author Harris Khalique.

Qazi’s verses are a celebration of his motherland and a reflection of his deep devotion to the land he belonged to. His poetry honors everything connected to his motherland, whether it is poverty, oppression, mourning, death, the sun, moon, river, wind, love, lonliness or life.

In Every Verse for You, Fazal Baloch has carefully selected works from Qazi’s ten anthologies, including a powerful poem titled Motherland from his debut collection Zarnawisht (Golden Verses, 1990). In this poem, Qazi expresses his profound admiration for his homeland and concludes with these evocative lines:

“Without motherland, existence fades,

But with it, we endure, forever thrive.”

Here, Qazi emphasizes the centrality of one’s existence to the land.

Another poem carrying the same tone appears in Qazi’s 2010 anthology, Mani Ahaday Gamay Kessah (The Sorrowful Tale of My Age). Titled The Pen Stands Ashamed, this poem continues Qazi’s vivid portrayal of his homeland. He opens with striking imagery:

“Blossoms of blood bloom in the mountains,

And roses sprout from youthful corpses.”

Here, he uses elements of nature to illustrate how oppression and brutality have stained the land. As the poem progresses, he moves from oppression to agony, from aggression to sheer brutality—yet ultimately, he leaves room for hope, a possibility of ending the suffering.

In the third stanza, he writes:

“My homeland has turned into a hell.”

And in the final lines, he delivers a searing condemnation of those in power:

“The wicked players in power’s filthy game,

Like leeches, draining the homeland’s veins.”

Qazi condemns the brutal and destructive practices carried out by those in power, who, driven by greed and self-interest, assist the oppressors in draining the life force of the homeland. This filthy game of power exposes the harsh realities of those who, blinded by their individuality, selfishness, and self-glorification, aid in the exploitation of their own land.

The pursuit of power has stifled the conscience they once had, making them not only complicit in betraying their nation but also indifferent to the collective consciousness of their people. Qazi compares these individuals to ‘leeches,’ draining the blood that symbolizes survival and prosperity. Their complicity in the destruction of the homeland contributes to its transformation into a living hell for its people.

For the inhabitants, the loss of blood signifies growing vulnerability and helplessness, both from external forces and within themselves.

Qazi’s use of language is rich with imagery yet remains simple and accessible, allowing his verses to be easily understood and recited by all. His poetry never wavered in its devotion to his homeland, fearlessly speaking against oppression while simultaneously offering hope. His words were an act of worship to his land.

In his 2012 collection, Hani Mani Maten Watan (Hani: My Motherland), one of the poems Fazal Baloch has translated is My Sacred and Holy Land. In this poem, Qazi’s endless love to his homeland is evident. He declares:

“For my motherland, I’ll endure every trial and torment.”

This line captures his willingness to bear any hardship for the sake of his land. His devotion reaches its peak in the concluding lines:

“Balochistan, my beloved motherland!

My faith and devotion,

My adoration for you knows no bounds.”

Here, Qazi elevates his homeland to a sacred status, intertwining love, faith, dedication. By using words like faith, devotion, and adoration, he conveys that his connection to Balochistan is not just patriotic—it is almost spiritual. His poetry reflects the belief that land is not merely a physical space but the very essence of identity and existence.

Art, as literary figures assert, is all about personal experience—an expression of feelings and emotions. When an artist lives through an era of injustice, it is only natural for their work to reflect those experiences.

Qazi, who witnessed oppression firsthand, never shied away from expressing it in his poetry. His fearless writing led to imprisonment, and his personal loss—the martyrdom of his only son, Dr. Kambar, a medical doctor by profession and a poet, who fought for Baloch rights—deepened his verses, filling them with both longing and pride.

In Every Verse for You, Fazal Baloch has translated several of Qazi’s poems dedicated to his son, whom he lovingly called Kambaro in his words. One such poem, Come Back, Kapin, from his 2016 collection Jungal Chencho Zeba Ent (The Jungle Sways in Beauty), captures the depth of a father’s grief and admiration. In the concluding lines, Qazi writes:

‘Kapin!

You’ve closed your eyes for a while,

Perhaps just a little tired.

Yet these mountains, these deserts,

these meadows, these fields,

They remember”Kapin! you as a valiant warrior.

Just a voice echoes in the air;

Motherland needs a son like you.

Come back, Kapin.”

These lines reflect the sorrow of a father who refuses to accept his son’s absence as permanent. “You’ve closed your eyes for a while, perhaps just a little tired.”—he frames death as rest, a momentary pause rather than an end.

Yet, his grief is not passive; it transforms into a declaration of pride.

The land itself—the mountains, deserts, meadows, and fields—becomes the custodian of Kambar’s memory, ensuring that his sacrifice is never forgotten.

In the final plea, “Come back, Kapin,” Qazi transcends personal longing. It is not just a call for his son’s return, but an invocation—an eternal echo summoning those who will rise in his place.

Qazi’s poetry is deeply powerful in its ability to capture the collective anxieties of the Baloch people, especially in the face of exploitation and loss. In the poem The Stranger, selected and translated from his anthology Hani Mani Maten Watan (Hani: My Motherland), Qazi’s tone is filled with concern and urgency.

The poem opens with the stark line:

“Behold! Gwadar is slipping away from our hands.

Tomorrow, in my own city,

I will wander like a stranger.”

In The Stranger, Qazi powerfully highlights the tragedy unfolding in Gwadar, where the city is slipping away from its residents. His verse reflects a dire prediction of the future, one marked by loss and erasure of identity. As he writes:

“The days of affinity will fade,

These homes, huts, and abodes will vanish,

Lanes and alleys will disappear.”

Qazi’s words point not only to the physical destruction of homes but also to the spiritual and cultural disintegration that accompanies such loss.

The line “these homes, huts, and abodes will vanish” represents the erasure of the very essence of Baloch identity—a deep loss of the life and history tied to these places. What is vanishing is not just the material, but the soul of the land, the collective identity that has defined its people for centuries.

The poem further forewarns of an impending destruction, with Qazi writing:

“Ships from fore lands will arrive,

Pollute and poison my sea.”

The metaphor of ships arriving from foreign lands signifies the intrusion of external powers, whose presence threatens the purity and sanctity of the Baloch homeland. The sea, a symbol of both sustenance and cultural pride, is being “polluted and poisoned,” representing how foreign influence corrupts not just the physical landscape but the very soul of the land.

In the final lines, Qazi paints a grim future:

“All these scenes and vistas

Will become an elusive dream,

Like a stranger everyone will seem.”

The transformation of reality into a distant, elusive dream encapsulates the disorienting and painful effect of oppression. The metaphor of “a stranger” in one’s own land reflects the loss of connection to one’s roots, a feeling of alienation in what was once home. This identity crisis—of being a stranger in one’s own land—is a fate worse than death for Qazi, symbolizing the obliteration of culture, heritage, and belonging, not just for one generation, but for those that follow.

The poem The Lonesome Ambience is from Qazi’s 2003 collection, Shag Man Sabzen Sawada (The Boat in the Blue Ocean). In this poem he turns his attention to the beauty and peacefulness of nature, celebrating the charm of Shall (Quetta) through simple yet vivid imagery. Qazi contemplates the quiet beauty of the city. In the opening lines,

“How beautiful is the lonesome ambiance of your city,

Dry autumn leaves fall upon the earth’s bosom.”

He praises the stillness of Quetta, drawing attention to the quietude and peacefulness of autumn. This tranquil scene contrasts sharply with the turmoil and unrest we often see in his other works. Through the falling leaves, Qazi suggests a sense of acceptance and peace—perhaps even finding solace in the inevitable cycles of life.

The following lines—

“When you flutter your moon-bright scarf in the air,

Each color of the rainbow subsumes within me.”

These lines further emphasize the connection between the natural world and his emotional state. The imagery of the scarf fluttering in the air conveys a sense of lightness and freedom, suggesting that these simple natural elements fill him with happiness and serenity.

In Lost and Found, a short poem from Qazi’s Zarnawisht, the themes of longing, solitude, and self-reflection are deeply explored. Qazi captures the emotional depth of unrequited desire and the painful realization of isolation, which resonates strongly throughout the poem. As he begins:

“Someone came

And knocked

On the door of my heart”

Here, he refers to a loved one whose presence deeply moved him. The mere sight of them stirred something within, shaking him to his core.

He further writes:

“I turned it wide

And found myself

Standing outside”

Through these lines, Qazi reveals that his heart had always been open, yearning for that presence. But in the end, he realizes he is alone—standing there with no one beside him.

The paradox of seeking and finding emptiness portrays the emotional turmoil of yearning for something that never materializes, a recurring theme of personal and existential loneliness in Qazi’s poetry.

Mubarak Qazi’s legacy is indeed indelible and immortal in the world of literature. His words transcend time, capturing the essence of his era and preserving it for generations to come. As Qazi says;

‘Mubarak endured pains like none ever did.

Mubarak composed poems like none ever said.

Mubarak lived a life like none ever led.’